In theory, wars should end when the defeated have no one left to fight and the victors can do whatever they likes. In practice, many if not most wars do not end in this way. As the end approaches and few doubts remain concerning the outcome, the loser will try and get the best terms he can; whereas the victor may be tempted to spare himself further effort, treasure and blood. Another possibility is for stalemate to prevail; causing both sides to have second thoughts about whether their goals can in fact be achieved and start to look for a way out.

In theory, wars should end when the defeated have no one left to fight and the victors can do whatever they likes. In practice, many if not most wars do not end in this way. As the end approaches and few doubts remain concerning the outcome, the loser will try and get the best terms he can; whereas the victor may be tempted to spare himself further effort, treasure and blood. Another possibility is for stalemate to prevail; causing both sides to have second thoughts about whether their goals can in fact be achieved and start to look for a way out.

In almost every case, the opening of negotiations will be marked by some kind of ceremony, great or small. Once they get under way they may be either direct or indirect. Direct negotiations mean a meeting, or more likely a series of meetings, between the representatives of both sides; indirect ones, meetings in which intermediaries play a prominent, sometimes decisive, role. During the Middle Ages conducting them was normally the task of the Church; shuttle diplomacy, made famous in 1973-74 by U.S Secretary of State Henry Kissinger as he flew between Jerusalem, Cairo and Damascus, is by no means a modern invention. A similar role is likely to be played by some neutral party or else by the United Nations. Negotiations may be limited to the actual belligerents, or else they may involve other parties as well. As happened, for example, during the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15, which was attended by delegations from almost every European state, and also during the Conference of Versailles in 1919-20.

Contrary to what many people think, peace-negotiations and fighting are by no means exclusive. Instead, very often they take place simultaneously. An excellent example was the so-called Hundred Years War. Starting in 1337 and ending in 1453, in reality it consisted of a whole series of wars, some simultaneous, some consecutive, with pauses in between. Throughout the hundred-and sixteen years it lasted there was probably not one in which peace negotiations did not go on; if not between the principals, i.e the kings of both countries, then between some of their subordinates who, under the prevailing decentralized feudal system, often enjoyed a considerable degree of freedom to do as they saw fit. One issue on which agreement was sometimes sought was an exchange of prisoners—just as it is today following the fall of Kherson.

The peace-negotiations surrounding the Thirty Years War started in 1635 but only ended in 1648 (not counting the closely related war between France and Spain, which went on until 1657). Attempts to end the Vietnam War got under way in 1969 but took four years to complete; just deciding on the shape of the conference table in such a way as to satisfy all the participants (the U.S, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong, and North Vietnam) required months.

Applying the above generalities to the current conflict in Ukraine, what can we reasonably expect? Point number one: most likely, negotiations will be indirect at first but direct later on. At present Zelensky is determined not to sit down with Putin’s representatives, let alone the man himself. But not sitting down with Putin does not necessarily mean that any kind of negotiation between Ukraine and Russia must be ruled out. Some kind of intermediary, most likely the UN or else a country, such as India, currently not involved in the conflict may be called in to provide its good services. Another possibility is that Putin will be remeoved by his own people and that his successors will prove more amenable to negotiations than he has been.

Point number two: very probably, given how numerous the NATO countries are and the fact that Putin has very few close allies, he will reject a peace congress and insist on one-on-one negotiations. Formally at any rate other countries will be excluded, though they may try to position themselves on the sidelines so as to gather what crumbs they can.

Point number three: almost certainly, the negotiations will take a long time to complete. At least months, more likely years. As they go on, the shooting may stop—or else it will continue, albeit intermittently and on a reduced scale. See, by way of an example of the way the two things can mix, the Vietnam War.

Point number four: seen from Moscow, victory—whatever that may mean—seems far away, perhaps even further than it did on the day its armies first launched their invasion nine months ago. On the Ukrainian side, even taking into account Zelensky’s recent victories, it does not look as if his proclaimed aim of ejecting the Russians from all of the territory they have taken since 2014 is at all realistic. It being impossible to settle the issue by force of arms, it is very likely that, in the end, some kind of compromise will be struck. One that, while granting Ukraine much of what it wants, will at any rate enable Putin to claim victory; for example, by means of a NATO declaration that Ukraine will not be allowed to join that organization.

Finally: this short article is based on nothing else but history. Often in the past history has proved itself a poor guide to the future. But it is all we have

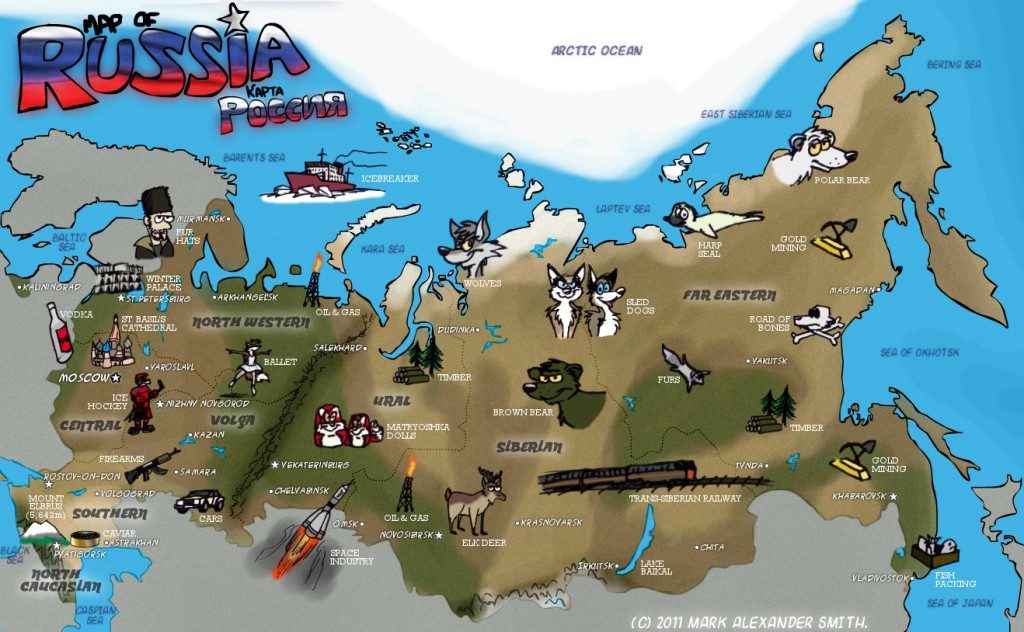

For a number of years now, I have been receiving regular emails from an outfit calling itself Russia Beyond. An offshoot of the government owned and run Russian news agency TV-Novosty, it specializes in what one could call “soft” propaganda—short, often quite amusing, stories about what life inside the world’s largest country is supposedly. One which, for good or ill, also happens to be one of the politically, militarily, economically, and culturally most important among them. Each issue is accompanied by the following warning:

For a number of years now, I have been receiving regular emails from an outfit calling itself Russia Beyond. An offshoot of the government owned and run Russian news agency TV-Novosty, it specializes in what one could call “soft” propaganda—short, often quite amusing, stories about what life inside the world’s largest country is supposedly. One which, for good or ill, also happens to be one of the politically, militarily, economically, and culturally most important among them. Each issue is accompanied by the following warning:

Shortly after Mr. Biden took office, I posted a short piece—No. 367, to be precise—on “What I Want of Joe Biden.” Now that the Congressional elections are just weeks away, I want to try and see the extent to which my

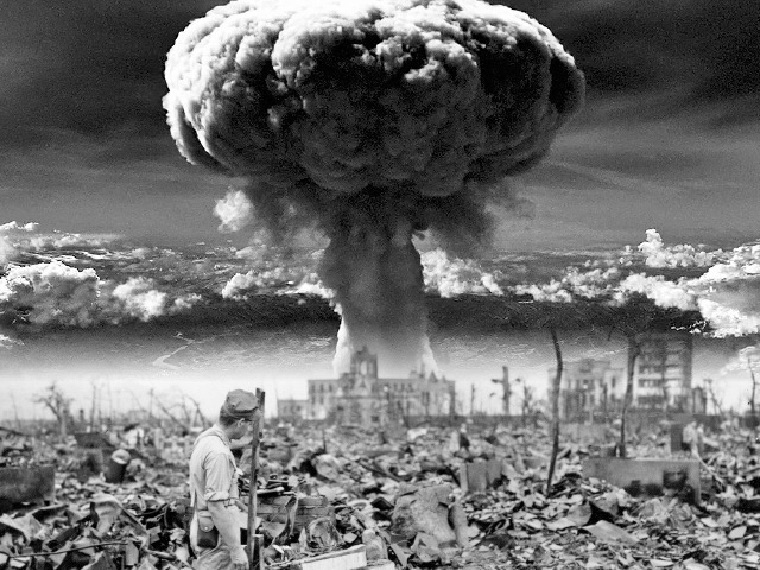

Shortly after Mr. Biden took office, I posted a short piece—No. 367, to be precise—on “What I Want of Joe Biden.” Now that the Congressional elections are just weeks away, I want to try and see the extent to which my To most people, whether or not a ruler or country “uses” nuclear weapons is a simple choice between either dropping them on the enemy or not doing so. For “experts,” though, things are much more complicated (after all making them so, or making them appear to be so, is the way they earn their daily bread). So today I am going to assume the mantle of an expert and explain some of the things “using” such a weapons might mean.

To most people, whether or not a ruler or country “uses” nuclear weapons is a simple choice between either dropping them on the enemy or not doing so. For “experts,” though, things are much more complicated (after all making them so, or making them appear to be so, is the way they earn their daily bread). So today I am going to assume the mantle of an expert and explain some of the things “using” such a weapons might mean.

Like most people these days, I sometimes feel the urge to spend an idle hour roaming the Net. Either because I have nothing better to do or out of curiosity. Doing so the other day, I came across a post I considered so curious that I decided to share it with you. Text taken from Wikipedia with a few very minor changes meant to make things shorter and clearer. Comments, welcome.

Like most people these days, I sometimes feel the urge to spend an idle hour roaming the Net. Either because I have nothing better to do or out of curiosity. Doing so the other day, I came across a post I considered so curious that I decided to share it with you. Text taken from Wikipedia with a few very minor changes meant to make things shorter and clearer. Comments, welcome.