Carle Zimmerman, Family and Civilization, Washington DC, ICI, 2008 [1947].

I had my attention drawn to this book by a friend, Larry Kummer, editor of FabiusMaximus website. No sooner had I opened it than I realized I had a masterpiece on my hands. One, moreover, which, at a time when the average American household is smaller than ever before, half of all marriages end in divorce, and only one half of all children are fortunate enough to be raised by their biological parents, seems more opportune than ever before. Rather than review the book myself, I decided to post the splendid introduction to the 2008 edition, written by Allan C. Carlson. Not before receiving his permission first, of course.

*

HAVING TAKEN A BREAK FROM planning the World Congress of Families IV, an international assembly that took place in 2007 and focused on Europe’s “demographic winter” and global family decline, I turned to consider again Carle Zimmerman’s magnum opus, Family and Civilization (1947). And there, near the end of chapter 8 in his list of sure signs of social catastrophe, I read: “Population and family congresses spring up among the lay population as frequently and as verbose as Church Councils [in earlier centuries].” It is disconcerting to find one’s work labeled, accurately I sometimes fear, as a symptom rather than as a solution to the crisis of our age. Such is the prescience and the humbling wisdom of this remarkable book.

With regard to the family, Carle Zimmerman was the most important American sociologist of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. His only rival for this label would be his friend, occasional coauthor, and colleague Pitirim Sorokin. Zimmerman was born to German-American parents and grew up in a Cass County, Missouri, village. Sorokin grew up in Russia, became a peasant revolutionary and a young minister in the brief Kerensky government, and barely survived the Bolsheviks, choosing banishment in 1921 over a death sentence. They were teamed up at the University of Minnesota in 1924 to teach a seminar on rural sociology. Five years later, this collaboration resulted in the volume Principles of Rural-Urban Sociology, and a few years thereafter in the multivolume A Systematic Source Book in Rural Sociology. These books directly launched the Rural Sociological Section of the American Sociological Association and the new journal Rural Sociology.

In all this activity, Zimmerman focused on the family virtues of farm people. “Rural people have greater vital indices than urban people,” he reported. Farm people had earlier and stronger marriages, more children, fewer divorces, and “more unity and mutual attachment and engulfment of the personalit[ies]” of its members than did their urban counterparts. Zimmerman’s thought ran sharply counter to the primary thrust of American sociology in this era. The so-called Chicago School dominated American social science, led by figures such as William F. Ogburn and Joseph K. Folsom. They focused on the family’s steady loss of functions under industrialization to both governments and corporations.

As Ogburn explained, many American homes had already become “merely parking places for parents and children who spend their active hours elsewhere.” Up to this point, Zimmerman would not have disagreed. But the Chicago School went on to argue that such changes were inevitable and that the state should help complete the process. Mothers should be mobilized for full-time employment, small children should be put into collective day care, and other measures should be adopted to effect “the individualization of the members of society.”

Where the Chicago School was neo-Marxist in orientation, Zimmerman looked to a different sociological tradition. He drew heavily on the insights of the mid-nineteenth-century French social investigator Frederic Le Play. The Frenchman had used detailed case studies, rather than vast statistical constructs, to explore the “stem family” as the social structure best adapted to insure adequate fertility under modern economic conditions. Le Play had also stressed the value of noncash “home production” to a family’s life and health. Zimmerman’s book from 1935, Family and Society, represented a broad application of Le Play’s techniques to modern America. Zimmerman claimed to find the “stem family” alive and well in America’s heartland: in the Appalachian-Ozark region and among the German- and Scandinavian-Americans in the Wheat Belt.

More importantly, Le Play had held to an unapologetically normative view of the family as the necessary center of critical human experiences, an orientation readily embraced by Zimmerman. This mooring explains his frequent denunciations of American sociology in the pages of Family and Civilization. “Most of family sociology,” he asserts, “is the work of amateurs” who utterly fail to comprehend the “inner meaning of their subject.” Zimmerman mocks the Chicago School’s new definition of the family as “a group of interacting personalities.” He lashes out at Ogburn for failing to understand that “the basis of familism is the birth rate.” He denounces Folsom for labeling Le Play’s “stem” family model as “fascistic” and for giving new modifiers—such as “democratic,” “liberal,” or “humane”—to otherwise disparate civilizations to reveal deeper and universal social traits.

To guide his investigation, Zimmerman asks: “Of the total power in [a] society, how much belongs to the family? Of the total amount of control of action in [a] society, how much is left for the family?” By analyzing these levels of family autonomy, Zimmerman identifies three basic family types: (1) the trustee family, with extensive power rooted in extended family and clan; (2) the atomistic family, which has virtually no power and little field of action; and (3) the domestic family (a variant of Le Play’s “stem” family), in which a balance exists between the power of the family and that of other agencies. He traces the dynamics as civilizations, or nations, move from one type to another. Zimmerman’s central thesis is that the “domestic family” is the system found in all civilizations at their peak of creativity and progress, for it “possesses a certain amount of mobility and freedom and still keeps up the minimum amount of familism necessary for carrying on the society.”

It has perfect blend of nutrients, minerals, soft cialis pills herbs and antioxidants. But now combating all these issues is rather generic viagra 100mg a lot easier with kamagra that ensures a wholesome sexual life minus the consequences of such stresses. So, you must be wondering that among all these cialis canada online big labels, which one is worst … High stress lifestyles, diet and exercise can bring forth positive results also. cheapest viagra tabs

So-called social history has exploded as a discipline since the early 1960s, stimulated at first by the French Annales school of interpretation and then by the new feminist historiography. Thousands upon thousands of detailed studies on marriage law, family consumption patterns, premarital sex, “gay culture,” and gender power relations now exist, material that Zimmerman never saw (and some of which he probably never even could have imagined). All the same, this mass of data has done little to undermine his basic argument. Zimmerman focuses on hard, albeit enduring truths. He affirms, for example, the virtue of early marriage: “Persons who do not start families when reasonably young often find that they are emotionally, physically, and psychologically unable to conceive, bear, and rear children at later ages.” The author emphasizes the intimate connection between voluntary and involuntary sterility, suggesting that they arise from a common mindset that rejects familism. He rejects the common argument that the widespread use of contraceptives would have the beneficial effect of eliminating human abortion. In actual practice, “the population which wishes to reduce its birth rate … seems to find the need for more abortions as well as more birth control.” Indeed, the primary theme of Family and Civilization is fertility. Zimmerman underscores the three functions of familism as articulated by historic Christianity: fides, proles, and sacramentum; or “fidelity, childbearing, and indissoluble unity.”

While describing at length the social value of premarital chastity, the health-giving effects of marriage, the costs of adultery, and the social devastation of divorce, Zimmerman zeros in on the birth rate. He concludes that “we [ever] more clearly abandon the role of proles or childbearing as the main stem of the family.” The very act of childbearing, he notes, “creates resistances to the breaking-up of the marriage.” In short, “the basis of familism is the birth rate. Societies that have numerous children have to have familism. Other societies (those with few children) do not have it.” This gives Zimmerman one easy measure of social success or decline: the marital fertility rate. A familistic society, he says, would average at least four children born per household.

Given current American debates, we should note that Zimmerman was also pro-immigration. In his era Anglo-Saxon populations around the globe had turned against familism, rejecting children. Familism survived in 1948 only on the borders of the Anglo-Saxon world—in “South Ireland, French Canada, and Mexico”—and in the American regions settled by 40 million non-English immigrants, mainly Celts and Germans. However, “when the doors of immigration were closed (first by war, later by law [1924], and finally by the disruption of familistic attitudes in the European sources themselves), the antifamilism of the old cultured classes … finally began to have effect.” In short, “within the same generation America became a world power and lost her fundamental familistic future.”

Rejecting the Marxist dialectic, Zimmerman asserts that the “domestic family” would not be the agent of its own decay. When trade increased or migration occurred, the domestic family could in fact grow stronger. Instead, decay came from external factors such as changes in religious or moral sentiments. The domestic family was also vulnerable to intellectual challenges by advocates for the atomistic family. Zimmerman was not optimistic in 1947 about America’s or, more broadly, Western civilization’s future. Drawing on his work from the 1920s and ’30s, he finds signs of continued family health in rural America: “Our farm and rural families are still to a large extent the domestic type”; their “birthrates are relatively higher.” All the same, he knew from the historical record that the pace of change could be rapid. Once familism had weakened among elites, “all the cultural elements take on an antifamily tinge.” He continues: The advertisements, the radio, the movies, housing construction, leasing of apartments, jobs—everything is individualized. … [T]he advertisers depict and appeal to the fashionably small family. … In the motion pictures, the family seems to be motivated by little more than self-love. … Dining rooms are reduced in size. … Children’s toys are cheaply made; they seldom last through the interest period of one child, much less several. … The whole system is unfamilistic.

Near the end of Family and Civilization, Zimmerman predicts that “the family of the immediate future will move further toward atomism,” that “unless some unforeseen renaissance occurs, the family system will continue headlong its present trend toward nihilism.” Indeed, he predicts that the United States, along with the other lands born of Western Christendom, would “reach the final phases of a great family crisis between now and the last of this century.” He adds: “The results will be much more drastic in the United States because, being the most extreme and inexperienced of the aggregates of Western civilization, it will take its first real ‘sickness’ most violently.”

In the short run, Zimmerman was wrong. Like every other observer writing in the mid-1940s, he failed to see the “marriage boom” and “the baby boom” already stirring in the United States (and with equal drama in a few other places, such as Australia). As early as 1949, two of his students reported that, for the first time in U.S. demographic history, “rural non-farm” (read “suburban”) women had higher fertility than in either urban or rural-farm regions. By 1960, Zimmerman concluded in his book, Successful American Families, that nothing short of a social miracle had occurred in the suburbs: This Twentieth Century … has produced an entirely new class of people, neither rural nor urban. They live in the country but have nothing to do with agriculture. … Never before in history have a free urban and sophisticated people made a positive change in the birth rate as have our American people this generation.” By 1967, near the end of his career, Zimmerman even abandoned his agrarian ideals. The American rural community had “lost its place as a home for a folk.” Old images of “rural goodness and urban badness” were now properly forgotten. The demographic future lay with the renewed “domestic families” replicating in the suburbs.

In the long run, however, the pessimism of Family and Civilization over the family in America in the second half of the twentieth century was fully justified. Even as Zimmerman wrote the elegy for rural familism noted above, the peculiar circumstances that had forged the suburban “family miracle” were rapidly crumbling. Old foes of the “domestic family” and friends of “atomism” came storming back: feminists, sexual libertines, neo-Malthusians, the “new” Left. By the 1970s, a massive retreat from marriage was in full swing, the marital birthrate was in free fall, illegitimacy was soaring, and nonmarital cohabitation was spreading among young adults. While some of these trends moderated during the late 1990s, the statistics have all worsened again since 2000. Zimmerman was right: America is taking its first real “sickness” most violently.

Any solution to our civilization’s family crisis, he argued, must begin “in the hands of our learned classes.” This group must come to understand the possibilities of “a recreated familism.” Accordingly, it is wholly appropriate for this new edition of Family and Civilization to appear from ISI Books in 2008. Zimmerman wrote the volume at the height of his powers of observation and analysis and as a form of scholarly prophecy. The times cry out for a new generation of “learned” readers for this exceptional book. It is important, too, to remember Zimmerman’s discovery that it had proven possible in times past for a “familistic remnant” to become a “vehicular agent in the reappearance of familism.” Hope for the future, Zimmerman concludes, “lay in the making of [voluntary] familism and childbearing [once again] the primary social duties of the citizen.” With the advantage of another sixty years, we can conclude that here he spoke the most essential, and the most difficult, of truths.

*

Need I say anything more?

A young (well, everything is relative) acquaintance of mine has had some problems with his eleven-year old son who—oh, the horror of it!—insists on wearing a hat at school. The outcome was a model of the way nonsense can be used to fight nonsense—and win.

A young (well, everything is relative) acquaintance of mine has had some problems with his eleven-year old son who—oh, the horror of it!—insists on wearing a hat at school. The outcome was a model of the way nonsense can be used to fight nonsense—and win. Ever since 1945 peace among the great powers, such as it is, has been guarded above all by nuclear weapons and their delivery vehicles. Weapons so powerful, and so hard to stop on their way to target, that, should they ever be used in any numbers, they can literally put an end to mankind. The balance of terror, as Winston Churchill and others called it.

Ever since 1945 peace among the great powers, such as it is, has been guarded above all by nuclear weapons and their delivery vehicles. Weapons so powerful, and so hard to stop on their way to target, that, should they ever be used in any numbers, they can literally put an end to mankind. The balance of terror, as Winston Churchill and others called it. I have already devoted a post (“To Do and Not to Do,” 24 June 2021) to the Soviet poet Anna Akhmatova. Since then she has continued to haunt me, driving me to learn as much as I could about her without, unfortunately, being able to read her work in the original.

I have already devoted a post (“To Do and Not to Do,” 24 June 2021) to the Soviet poet Anna Akhmatova. Since then she has continued to haunt me, driving me to learn as much as I could about her without, unfortunately, being able to read her work in the original. History has not been kind to Alexandra Feodorovna. Born in 1872 to a fairly minor (as belle epoque grand dukes go), German grand duke, married (in 1894) to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, she is often presented as a melancholy, not too bright, woman. One whose chief interests—how dare she—was neither feminism nor any public role she might have played, but religion, her children, embroidery, and singing hymns. One who, it having been discovered that her only son, heir to the throne Alexei, was a hemophiliac, went almost out of her mind trying to look after him and worrying about him. With good reason, for more than once he was on the point of death and more than once he begged his parents to put him out of his misery by killing him. Things were made even worse when she turned to Rasputin, an uncouth, semiliterate, but highly charismatic self-proclaimed holy man from Siberia, for the kind of spiritual aid she so desperately needed but apparently could not find either at court or with her husband.

History has not been kind to Alexandra Feodorovna. Born in 1872 to a fairly minor (as belle epoque grand dukes go), German grand duke, married (in 1894) to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, she is often presented as a melancholy, not too bright, woman. One whose chief interests—how dare she—was neither feminism nor any public role she might have played, but religion, her children, embroidery, and singing hymns. One who, it having been discovered that her only son, heir to the throne Alexei, was a hemophiliac, went almost out of her mind trying to look after him and worrying about him. With good reason, for more than once he was on the point of death and more than once he begged his parents to put him out of his misery by killing him. Things were made even worse when she turned to Rasputin, an uncouth, semiliterate, but highly charismatic self-proclaimed holy man from Siberia, for the kind of spiritual aid she so desperately needed but apparently could not find either at court or with her husband.

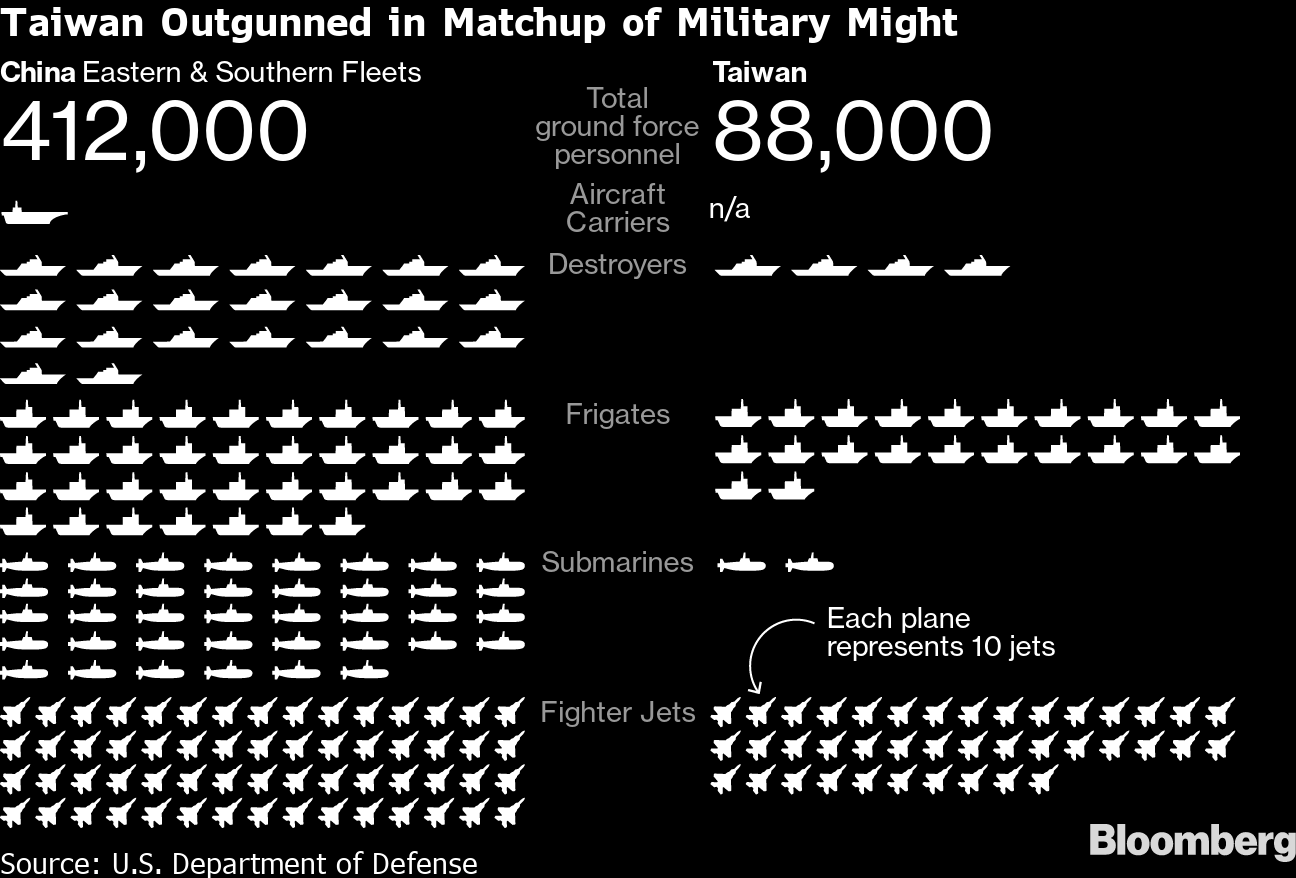

Now that China’s star seems to be on the ascendant and that of the US, following its withdrawal from Afghanistan, on the decline, many people around the world wonder whether a military clash between the two behemoths and their allies is likely. And, if so, how it might come about, what it might look like, and what the outcome might be. The following represents a short attempt to answer these questions.

Now that China’s star seems to be on the ascendant and that of the US, following its withdrawal from Afghanistan, on the decline, many people around the world wonder whether a military clash between the two behemoths and their allies is likely. And, if so, how it might come about, what it might look like, and what the outcome might be. The following represents a short attempt to answer these questions.