Years ago when I was still at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, I used to teach a course named Early Modern Political Thought. Judging by the feedback mechanism’s results, it was the most successful course I ever gave—it regularly got 19 out of 20 possible point. So I repeated it many times. Focusing on original sources, we read parts of the works of Desiderius Erasmus, Nicolò Machiavelli, Emperor Charles V (the 1543 testament), Jean Bodin, Thomas Hobbes, Robert Filmer, John Locke, and, when there were still some meetings left, Charles de Montesquieu.

Like most freshmen in most countries the students, most of them 21-22 years old and fresh out of the military, did not know anything about anything. To help them along while at the same time avoiding a waste of time, I made them do two things. First, prior to each meeting they were to read the assigned chapters. Second, each time we finished with one author and moved to the next one they were to present me with a short essay—about 1,000 words—explaining who he was, what he had written, and so on. I did not ask them for footnotes, but I did ask that they list the books or articles they had consulted. It worked; week by week, I would collect their essays, read them quite carefully, and annotate them; week by week, I saw their work improving. They in turn were very grateful, even to the point of telling me that my course was the best of the lot.

Since then much has changed. Probably the most important change has been the rise of political correctness, a monster if ever one there was which has made teaching literature, history and social science almost impossible. That, however, is not the development I want to talk about here. What I do want to talk about is the following text. It was composed, not by a human being but by an AI mechanism and available at ChatGPT. Having duly checked in, I asked it to provide me with a short essay about Machiavelli’s life and work. Soon it came up with the following text:

Niccolò Machiavelli is considered one of the most influential political philosophers in history, with his ideas and theories influencing political leaders for centuries. Born in Florence, Italy in 1469, Machiavelli was a diplomat, political philosopher, and writer during the Renaissance period.

One of Machiavelli’s most well-known works is “The Prince”, a political treatise that explores the concept of power and how leaders can maintain it. In this work, Machiavelli argues that rulers should be willing to do whatever is necessary to maintain their power, even if it means acting in ways that are considered immoral or unethical. This idea became known as “the ends justify the means”, and it has been widely debated and discussed by political philosophers and leaders throughout history.

One of the key themes in “The Prince” is the idea of “raison d’etat”, or the belief that the needs and interests of the state should always come before the needs and interests of the individual. According to Machiavelli, a leader should prioritize the well-being and stability of the state above all else, even if it means disregarding the rights and freedoms of the citizens. This idea is reflected in Machiavelli’s famous quote, “The first rule of a prince is to be able to be not good, if that is required to maintain his rule.”

Another key concept in “The Prince” is the idea of “fortuna”, or the role that luck and chance play in the success of a leader. According to Machiavelli, a leader should be aware of the role that luck and chance play in their success, and should be prepared to adapt to changing circumstances. However, he also believed that a leader could influence their own luck by being proactive and making decisive actions.

In addition to “The Prince”, Machiavelli also wrote a number of other influential works, including “The Art of War” and “The Discourses”. In these works, he explored themes such as the importance of military strategy and the role of citizenship in a republic.

One of the main criticisms of Machiavelli’s ideas is that they promote immoral and unethical behavior. Some have argued that his emphasis on the needs of the state and the willingness to use any means necessary to achieve power can justify authoritarianism and the suppression of individual rights. Others have argued that his ideas are necessary in order to maintain stability and protect the state.

Despite these criticisms, Machiavelli’s ideas continue to be widely studied and debated by political philosophers and leaders today. His work has had a significant influence on the development of modern political thought and continues to be a major influence on political leaders around the world.

In conclusion, Niccolò Machiavelli was a political philosopher whose ideas continue to be widely studied and debated today. His most famous work, “The Prince”, explores the concept of power and how leaders can maintain it, and his ideas have had a significant influence on the development of modern political thought. While some have criticized his ideas for promoting unethical and immoral behavior, others argue that his ideas are necessary in order to maintain stability and protect the state. Regardless of one’s perspective, it is clear that Machiavelli’s work has had a lasting impact on political thought and leadership.

Not half bad, don’t you agree? A bit pompous, yes. A bit bland. As if someone had decided to leave out anything a little bit interesting, let alone provocative or innovative; which, judging by what has been published about the way the program was created, is just what “someone” had done. But presumably good enough to pass the Turing test. Logically put together, without many of the things I used to warn my student against for years on end; such as leaps of thought, repetitions, or obvious semantic and grammatical errors. Better stuff than many students can produce on their own. Certainly not without having devoted some thought to what to put in (and in what order), what to leave out, why, and how; and so on, and so on.

Which, after all, is precisely what the exercise I made them do was all about and why they enjoyed doing it as much as they did.

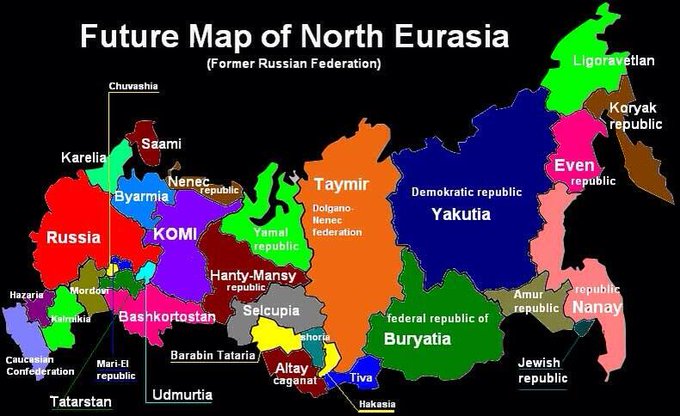

The tug-of-war concerning responsibility for the missiles that made their way into Poland a couple of weeks ago, killing two people, is by no means the first of its kind. What follows is a very short list of more or less similar incidents that took place over the last eight decades or so.

The tug-of-war concerning responsibility for the missiles that made their way into Poland a couple of weeks ago, killing two people, is by no means the first of its kind. What follows is a very short list of more or less similar incidents that took place over the last eight decades or so.