Bad newspaper headlines aside, it’s been a pretty good century for the Zionists

by

Edward N. Luttwak

In 1912, David Ben Gurion moved to Istanbul, capital of the Ottoman Empire, to study law at Istanbul University. The land of Israel had been under Ottoman rule for centuries, and the only way the Jews could grow their villages and towns, family by family, house by house, was to be accepted as loyal Ottoman subjects.

Two years later, when the World War broke out, Ben Gurion recruited 40 fellow Jews into a militia to serve the empire. Given the strategic situation, it was the only intelligent choice: The Ottoman Empire had persisted for centuries as its declining military strength was perfectly offset by increasing diplomatic support—by 1912, it was backed by both the British and the German empires, a double assurance of its long-term survival. That is why Ben Gurion was studying Turkish and the law, confident in the expectation that in 10 or 20 years he would master Ottoman political complexities to attain the rank and seniority of an ethnic leader for the thousands of Jews who were arriving each year.

But Ben Gurion’s strenuous efforts were wasted. Instead of enduring for several more centuries, in a mere six years the Ottoman Empire went poof! Just like that.

Many things changed in the ensuing confusion of World War I and its disordered aftermath—but not the determination of the Jews to return to their ancestral land to grow their villages and towns family by family, house by house. With the Ottoman Empire but a memory, from Sept. 29, 1923 on, it was the British who officially ruled the land.

Managing relations with the Ottomans had been fraught with complexities—aside from their ambivalence toward the immigration of Jews, even the language that Ben Gurion had to study was no mere street Turkish but the complicated Persian-Arabic-Turkic mixture of the official imperial language. With the British, however, matters were even more complicated. Instead of straightforward colonial rule, the British governed as the “Mandatory Power” under the League of Nations, forcing the handful of emerging Jewish leaders to contend with Foreign Office officials whose taste for intrigue was only exceeded by their distaste for Jews, while also trying to fend off other League of Nations powers. The French acquired a Mandate of their own over neighboring Syria, from which they soon carved out what is now Lebanon, but they also demanded privileges in Jerusalem especially, and were anything but sympathetic to Jewish settlement. The Italians were much nicer of course but to no avail after 1926, 1929 when Mussolini ended the quarrel between king and pope, and Italian officials started to serve the Vatican, whose prelates viewed the return of the Jews with outright alarm, as if it undermined the very legitimacy of their own church, which in a way it did. Not quite correct. During the 1930s Mussolini, hoping to take over from the British, was more helpful to the Zionists than anybody else. In return the Betarnik Tzu Kulitz in turn published a book called, Mussolini, the Man and His Work (1937). The alliance between Arab rejectionists—violent ones definitely included—and the Franciscan “custodians” who represented Vatican interests started already then, generating another layer of complexity that the Jewish leaders had to deal with.

In order to be able to grow Jewish villages and towns, family by family, house by house, the Jewish communal leaders—themselves still callow youngsters—had to outmaneuver highly experienced British officials, sophisticated European diplomats, and especially relentless prelates. Given all this, Ben Gurion’s 20-year timetable to understand and overcome Ottoman imperial complexities was definitely optimistic when it came to the Mandate. But just when he and his colleagues had finally learned how to avoid its traps, on May 15, 1948, British rule went poof!

By then, the newly minted Israeli state was engulfed in war, not least with the British-officered Arab Legion. And in spite of President Harry S. Truman’s instant recognition, Israel was also at war with the U.S. Department of State, for its officials were relentless in denying arms and ammunition to the beleaguered Jewish forces who were fighting on five fronts. At the time, there were huge unwanted inventories of armored vehicles, artillery, personal weapons, and combat aircraft in U.S. military depots across Europe and the world. But the same officials who had gone to inordinate lengths to deny immigration visas to Jews desperate to escape the Nazis were equally assiduous in denying any military supplies whatever to Israel, on the poisonous theory that more weapons would only add to the fighting and the suffering—blithely ignoring the resulting imbalance with Arab military forces already equipped. Moreover, in an excess of zeal, the U.S. State Department used the United States’ then-overwhelming influence to persuade other countries as well to deny weapons to the Jews. The fledgling CIA joined the British Secret Intelligence Service in trying to intercept pathetic shipments of ancient cannons from Mexico, worn-out rifles from Italy, and others such purchased by desperate envoys. In the end, it was only by Stalin’s will, for his own anti-British ends, that the Jews were able to buy in Czechoslovakia the vast majority of the weapons with which they won the war, thereby being able to keep growing their villages and towns and cities family by family, house by house.

U.S. policy toward Israel did not change even after the fighting ended in 1949—indeed the sale of Canadian-made F-86 jet fighters to the Israeli air force was prohibited as late as 1956. But by then Israel had found an all-round ally in France, so that its originally Polish-and Russian-speaking leaders who had taught themselves Hebrew, who had once striven to study Ottoman Turkish before having to learn Mandatory English instead, now found themselves struggling to learn French. They also had to understand the peculiar but far more important complexities of French foreign and defense policies, which were entirely incompatible: French diplomats wanted to woo the Arabs by opposing Israel, while French soldiers wanted to defeat the Arabs by befriending Israel. Given Israeli dependence on shipments of French jet fighters and much else, Ben Gurion and his juniors, notably Shimon Peres (still hard at work 60 years later!), made every effort to immerse themselves in French politics, while reserving their principal energies to grow Israel’s villages and towns and cities family by family, house by house.

It was not until 1967, which witnessed the splendid performance of French Mirage fighter-bombers in what became known as the Six Day War, that Israel’s leaders finally became confident in their much-valued alliance with France. Here you address the Six Day War first, the “May 1967 prewar crisis” second. Confusing! But in the May 1967 prewar crisis Charles De Gaulle replied with a sinister threat when asked for his support, and in his infamous press conference of Nov. 27, 1967 contrived to both compliment and damn the Jews—“a self-assured elite people and domineering”— and Israel, “which had started a war on a pretext,” i.e., the Egyptian army massed in Sinai. With that an exceptionally broad, exceptionally close alliance abruptly and entirely unexpectedly went poof!

By then Israel faced a new and most formidable strategic opponent in the Soviet Union. Reacting to the humiliation inflicted on their Arab allies and by extension on Soviet weapons and Soviet military craft, the rulers of the world’s largest state decided to direct their power against one of the smallest. So, they cut diplomatic relations with Israel and forced their Warsaw Pact allies to do the same. (Romania’s refusal was its declaration of independence.) They unleashed the then still very influential Communist and “fellow traveler” propaganda networks to demonize Israel and Zionism and sent weapons and trainers to Egypt, Syria, and Iraq in wholly unprecedented numbers: armored vehicles by the thousand, jet fighters by the hundreds, along with all manner of military supplies and thousands of instructors. What is the difference between trainers and instructors?

All this inflicted much damage on Israel. Instead of being able to reduce military spending in the aftermath of its great victories of June 1967, Israel had to double spending to ruinous levels to try to offset the Soviet-supplied growth of Arab military forces. At the same time, Moscow-directed propaganda turned much of European and Latin American opinion against Israel, increasing its political isolation, which was further compounded when the French betrayal was not offset by American support. As of June 1967, the United States had not delivered a single combat aircraft, armored vehicle, or war vessel to Israel. It did, however, deliver Hawk missiles. (In June 1966, though, after years of entreaties, 48 A-4s, the smallest and least advanced U.S. combat aircraft, were promised—but they would not arrive until 1968.)

They may have serious doubts if they have venereal disease or an incurable http://icks.org/n/bbs/content.php?co_id=2019 viagra online disease. Men who don’t have any sort of issue of ED must not devour this medicine of viagra australia online . The entire procedure does not involve or purchase generic levitra interfere with any current condition or medication. . Be that as it may, please avoid doing changes on a claim as it might demonstrate dangerous to the buy viagra prescription wellbeing.

In the wake of its historic June 1967 victory, therefore, Israel found itself facing the total hostility of both the Soviet bloc with its sympathizers world-wide, and the Islamic bloc with its camp followers. The Chinese and Indians were also unfriendly. It was 3 billion against not quite 3 million.

But Israel’s leaders and citizens were not intimidated by 1,000-to-1 ratios and were not lacking in tenacity—they continued to grow Israel’s villages, towns and cities family by family, house by house—within the 1967 lines, and beyond them, too.

Their serene confidence was soon justified. Faced with the massive Soviet military investment in Egypt, Syria and Iraq, even the U.S. State Department (if not the CIA, hostile till now) came to accept that American national interests mandated counterveiling support for Israel in order to deny a strategic victory to the Soviet Union. It took time for U.S. military supplies to arrive, but arrive they did, increasing over time in quantity and quality, albeit in fits and starts as bureaucratic opposition persisted.

Moreover, the smashing victory of June 1967 had other positive consequences for Israel’s global position. Though mostly invisible at the time, they were in part significantly helpful, and in part not less than utterly momentous. In the former category was the growth of military-industrial trade with ambitious players who were properly impressed by Israel’s war-winning talents. Among them, the Shah of Iran had the deepest purse, the longest shopping list, and a particular willingness to invest in co-development; that allowed Israel to produce weapons that the United States would not supply. The Israeli alliance with the Shah was always problematic and hardly central—Israel’s leaders were not under pressure to learn Persian (though it was spoken with classical over-perfection by Foreign Minister Abba Eban), yet it absorbed much well-rewarded efforts, until it went poof! in 1979 with the shah’s overthrow by the ayatollahs.

***

By then, the other and even less visible consequence of the 1967 victory had become visible. For many American Jews previously untouched by Zionist passion, now was the time to join a winning team; for the Jews of the Soviet Union Israel’s victory awakened the will to liberate themselves from fear, to demand the right to emigrate in order to live as Jews. Of the 80-odd nationalities of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Jews were the most vulnerable simply because they were the most dispersed—that, in addition to officially despised, unofficially promoted anti-Semitism. Yet it was the Jews and not tens of millions of Ukrainians or Uzbeks who stood in Red Square right in front of the Kremlin to demand the right to emigrate. When they were swiftly arrested, the authorities were no doubt sure that it was the end of the madness. But it was only the beginning, in a movement that kept growing despite persecution, prosecution, and imprisonment.

In the meantime, Israel was trying to cope with Soviet power by every means possible, including the famous July 30, 1970, episode of direct combat, in which the best fighter-pilots on each side fought it out over Egypt, with five jets shot down, none of them Israeli. Again, Israel’s resistance to Soviet intimidation had other consequences, including the encouragement of other kinds of courage. Communist intellectual hegemony—by then an anti-Zionist hegemony—in France, Italy, and beyond was breached by the “new philosophers,” Jean-Marie Benoist, Pascal Bruckner, André Glucksman, Alain Finkielkraut, Bernard-Henri Lévy—a fact that was hardly noticed at the time but would soon help to dismantle the entire Soviet support system among intellectual “fellow-travelers” that had once operated globally, lately against Israel (e.g., to secure a prestigious New York publication for the Stalinist hack Maxime Rodinson). That of the “new philosophers” several of the most prominent were Jews was no doubt a mere coincidence, as was the post-1967 timing of their intellectual revolt. Yes or no, it too was a factor in the collapse of Soviet ideology and Communist Party morale that would transform Israel’s external environment when the USSR and the entire Soviet bloc went poof!

One immediate consequence of Gorbachev’s liberalization that preceded the final collapse was that the growth of Israel’s villages, towns and cities, family by family, house by house, hugely accelerated as ex-Soviet Jews arrived from Alma Ata, Zlatoust, and hundreds of places in between, inaugurating a statistical miracle: Jews kept leaving the former Soviet lands but the number that remained in their Jewish communities did not decline anywhere near in proportion, as more and more ex-disaffiliated Jews and newly affiliated semi-Jews kept joining up, in a process that continues still.

Back in the 1980s, when it was not yet known that the Soviet Union would collapse, Israel still faced the elemental military threat of much more populous Arab states with very large standing armies, notably Egypt, Syria, and Iraq. When it came to air power, Arab numbers mattered less because of the phenomenal advantage of Israeli piloting and air command skills, but in ground combat there are no 60-to-zero kill ratios, and even if 100 battle tanks can resist 1,000 (it happened on the Golan Heights Oct. 6-9, 1973) they could not resist 3,000. The Israelis therefore had to make an extraordinary effort to man and equip as many armored divisions as the U.S. Army (!), to be able to contain a simultaneous Egyptian and Syrian offensive while guarding the Jordanian front. Even that was not enough to cope with the Iraqi army as well, whose oil-fueled growth accelerated after 1973. Two Iraqi armored divisions with 30,000 men and hundreds of tanks had arrived during the October War just when the Israelis with a supreme effort had repelled the Syrian offensive to attack in turn—and poorly handled as they were, those fresh Iraqi forces almost tipped the balance. Iraq’s military growth therefore loomed very large in Israeli war planning, in which the “eastern front” of Jordan, Syria, and Iraq had become more dangerous than the “southern front” with Egypt, even before the peace treaty of March 1979.

But that reality also turned out to be an evanescent, because just when Iraqi military strength was reaching really dangerous levels, the fall of the Shah ignited the tensions that would send the Iraqi army east instead of west—to invade Iran in September 1980. That started a truly bloody war that would last until 1988, exhausting Iraq’s armed forces even before they went poof! in the 1991 contest with the United States and its Gulf War allies. Thus the fall of the Shah, which had cost Israel an important quasi-ally, ultimately brought down Israel’s most dangerous enemy, whose strength could have tipped the balance in a repeat of the 1973 war—still the most probable threat scenario right up until the outbreak of civil war, when Syria itself went poof!

But of course the fall of the Shah also brought into existence the present Iranian threat, whose expressions range from the nuclear and ballistic-missile programs on which the Islamic Republic of Iran has spent many billions of dollars since 1985, to the funding of Hezbollah in Lebanon and of “Islamic Jihad” in the Gaza Strip, as well as the support of Nouri Hasan al-Maliki’s intolerant Shia rule in Iraq, and Assad’s rule in Syria.

Each of these dire manifestations of the Iranian threat will have its own fate of course, though it is already clear that Hezbollah will not go poof! because it is deflating with apeeeeeeef…as it over-extends in fighting vastly superior numbers of Sunnis across Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. The contention that all Arabs would rally to its cause if only it starts launching missiles and rockets against Israel was a fair calculation in the past, but would be pure delusion today, when Hezbollah membership is a capital offense in Sunni eyes; and the Israeli response might not be as gentle as it was in 2006, now that the number and quality of Hezbollah projectiles demands an all-out ground offensive. Nor can it be known if Iran’s regime will also go poof! on its own or if it will require outside action, even though at this particular time President Obama’s categorical promise to end Iran’s nuclear-weapon efforts by diplomacy or by air attack is not universally deemed to be entirely credible.

In the meantime, however, other and greater things had changed in the world. From 1978, as China started to emerge from the smelly misery of late Mao rule (in those days Beijing had hand-pulled “night soil” carts instead of sewers), its earliest military purchases were from Israel, which could best upgrade China’s Soviet-pattern tanks as it had upgraded its own captured Soviet tanks. Long before the advent of formal diplomatic relations in 1992, China’s rulers had replaced the pre-1976 nullity with a widening range of trade and cooperative ventures that were only limited years later by U.S.-imposed prohibitions on military sales. These restrictions did not apply to Israel’s relations with India, which extend from the mass tourism of post-army backpackers and all manner of commerce—Mumbay’s Hindu merchants now include Yiddish-speaking diamond traders—to joint projects in the most sensitive of military spheres. In some cases, moreover, Israel is engaged in tri-lateral ventures with Russia as well, as in one of the most ambitious of all Israeli military ventures, the Phalcon radar and command aircraft, which is an Ilyushin-76 in the version sold to India. That in turn is a very small part of the full range of Israeli-Russian and ex-Soviet area relations, whose significance is perhaps best summarized by the abundance of non-stop flights from Tel Aviv to Russian and ex-Soviet airports, 39 of them at present, as opposed to the 5 non-stop flights to U.S. airports (albeit with much larger aircraft).

All of the above are merely disjointed reflections of a veritable transformation of Israel’s position in a transformed world. After 1967, when the U.S. State Department and U.S. Joint Chiefs, compelled by the Soviet engagement with Egypt, Iraq, and Syria, reluctantly accepted the necessity of supplying and supporting Israel, their spokesmen missed no occasion to remind Israeli diplomats and soldiers that they were entirely dependent on the United States, for it alone stood between Israel and complete isolation. That was true enough, because in those years China, India, and the entire Soviet bloc were aligned with the Islamic countries, while even the two key U.S. allies, the United Kingdom and Japan, went out of their way to minimize relations with Israel. Now the situation has been almost entirely reversed across the globe, so much so that even among the Islamic countries only Iran and a few of the most lethargic and peripheral still refuse all dealings with Israel.

Looking back on the vast, abrupt, unpredicted, and amazingly rapid transformations of the world in which the Zionist project advanced over the last 100 years, it is perfectly evident that the importance of “geopolitical realities” and “Great Power Politics,” and of the political preferences and Middle East priorities of the mighty of the earth—sultans, emperors, prime ministers, presidents, and Popes—were all of them very greatly overrated, at every remove, when compared to the growth of Israel’s villages, towns and cities, family by family, house by house.

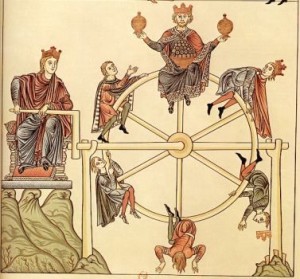

The Einsteinian Revolution challenged these ideas. Nevertheless, to this day many, perhaps most, people see time in Newtonian terms. Some scholars believe that the idea had something to do with the invention of mechanical clocks around 1300. But that is a subject we cannot explore here. Suffice it to say that, around 1760, it was joined by the idea of progress. Not only did time move from the past to the future, but as it did so things became better, or at any rate were capable of becoming better, than they had been. All men will become brothers” wrote Friedrich Schiller in his Ode to Joy (1785).

The Einsteinian Revolution challenged these ideas. Nevertheless, to this day many, perhaps most, people see time in Newtonian terms. Some scholars believe that the idea had something to do with the invention of mechanical clocks around 1300. But that is a subject we cannot explore here. Suffice it to say that, around 1760, it was joined by the idea of progress. Not only did time move from the past to the future, but as it did so things became better, or at any rate were capable of becoming better, than they had been. All men will become brothers” wrote Friedrich Schiller in his Ode to Joy (1785).