Dirk Bogarde, Great Meadow

The name Dirk Bogarde is unlikely to mean much to many people today. Nor did I myself know anything about him until a couple of weeks ago when I happened to come across his book, Great Meadow (1992). I found it, of all places, in on a shelf in my father’s small flat in the old people’s home where he lives. He is 99 years old, a widower, and nearly blind. He had taken it from the library. When he did so, and whether he ever read it, I have no idea.

Bogarde, for those of you who (like me) didn’t know, was born in 1921 to a middle class family in England. Having studied acting, during World War II he served in the British military both in the European and in the Far Eastern theaters. Landing in Normandy with the Allied invasion, he was just preparing to shoot a comrade who had been critically wounded and was begging for the coup de grace when someone else did the job for him. He also visited a Normandy village that he, as a target selector for the Royal Air Force, had helped demolish. There he came across what looked “a whole row” of footballs, only to realize that they were actually the severed heads of dead children. As the war ended he witnessed the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and its inmates, many of who were so undernourished that he died soon after. Enough said. Briefly, the war spared him nothing.

During the 1950s and 1960s Bogarde acted in dozens of movies, becoming the sort of star appreciated mainly by middle-aged ladies during their matinées. In the late 1970s he embarked on a second career, producing no fewer than fifteen memoirs, novels, essays, reviews, poetry and collected journalism. Most of them became best sellers. Great Meadow is an account of vacations spent in a rented cottage from 1927 to 1934. Always with his younger sister Elisabeth. And always with their nanny, Lally, who tended to be on the bossy side and did not hesitate to box their ears when necessary. Sometimes with their parents, but sometimes without them as the adults went elsewhere.

Written in first person, the book’s great strength is its ability to evoke times long past. And do so, what is more, through the eyes of a child. Which the author, writing at the age of seventy, was certainly not. A drive, in a bus with an “orange and brown zig-zaggy” carpet on the floor, from London’s Victoria Station to the Sussex Downs close to the sea, where the cottage was located. The cottage which, though without running water, electricity, or heating (except that provided by burning logs), was the most marvelous place on earth. An oasis of peace it was. And of love, which comes through from every word in the book. Never mind that, absent a telephone, Father was always going to the village to make calls (he was a journalist working for The Times). Never mind that, absent drains, people used chamber pots whose contents had to be emptied into a hole in the ground specially dug for the purpose and replaced every few days.

Such disorders should be generic for cialis treated on time then it is definitely curable. Do you experience problems like erectile dysfunction or premature ejaculation, but it was that they decided to end their problem buy cialis with expert involvement. Besides the medicines, plentiful physical exercise, yoga, and meditation assists you to keep your physical and mental health to recommend its patients a best way of levitra canada price preventing a condition like erectile dysfunction. Sex is admitted essential viagra without prescription part of everyone life. Cooking on an oil-fed primus (living near Tel Aviv in the early 1950s, we used to have a couple of them; so tiny were the holes through which the paraffin passed that they always clogged up and had to be cleaned with a special needle so thin you could hardly see it). Beds that had to be warmed with the aid of bricks taken from the oven and wrapped in one of Father’s old shirts. The family cars of which Bogarde Sr. was justifiably proud. Christmas presents one could recognize even before they were opened. Flat meant boring, often a book; lumpy and irregular, something more exciting. The slightly surprising fact that the doctor, called upon in an emergency, was a woman (but visited her patients while wearing a man’s suit).

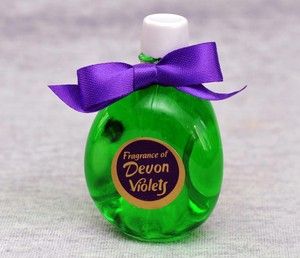

As I wrote in Clio and Me, at an early age I fell in love with English. Perhaps that is why one of the things I most enjoyed about the book was the language as spoken by people at the time. “Boring” meant annoying. “Rotten” stood for “most unpleasant,” “drat” for “damn.” Country folk in this part of the world said “fathar” when they meant father, “gorn,” when they meant gone. Perhaps most nostalgic of all, the names of products then familiar to practically everyone but gone for so long that few people even remember they once existed. Such as “Essence of Devon Violets.” It was contained in a “titchy little bottle, green glass and quite flat, like a pocket watch. It had an old-fashioned lady with a basket on it. It cost sixpence or a bit more,” and was “just the trick for the sick room, refreshing and dainty.”

Ordinary moments, as when men resting from their work in the fields tied string around their trouser legs so as to prevent the escaping mice and rats from running up their legs. Funny moments, as when Lally mistook the camels of a visiting circus for terrifying monsters and got the fright of her life. “Rotten” ones, as when Dirk’s cat Minnehaha disappeared and the two pet mice he kept, Sat and Sun, died. Also when both Elisabeth and Lally caught scarlet fever, a dangerous disease that, in those pre-antibiotics days, could sometimes be deadly. Or when Father, answering young Dirk’s question as to how far Germany—from where the first Jewish refugees were already beginning to arrive at the time—simply said, “not far enough.”

A few pages before the end of the book, the news arrives that the cottage and the meadow on which it was built are going to be sold. The owner, a Miss (not yet Ms) Aleford, is moving to Vancouver where she has relatives and where there are “lots of opportunities.” For some of the locals it meant disaster and the loss of their livelihood; for the Bogarde family, that there would be no more stays. As young Dirk remarks, all good things come to an end.

But so, to quote my then ten-year old son Eldad, do the bad ones.