The first Pussycat article, posted here on 21.5.2014, dealt with the frequent defeats of modern Western armed forces at the hand of irregulars in the Middle East, Asia and Africa and pointed out some of the underlying causes behind this phenomenon. Pussycats II, posted on 24.9.2014, explained how war was associated first with excellence, then with honor, then with wisdom (“the ultimate experience”) and then with PTSD. Whereas Pussycats III, posted on 8.10.2014, traced the way in which, time after time, rude but brave conquerors were turned into soft, lazy, effeminate losers. Here I want to analyze the contribution of yet another factor: to wit, the rise of the right to say no.

Principled resistance to military service can be traced as far back as early Christianity under the Roman Empire. Whether, at that time, it was rooted in moral objections to war as such or in religion has long been moot. The fact that, no sooner did the empire turn Christian in the fourth century A.D, many Christians started joining the army suggests that the latter interpretation is closer to the truth. Once God had told Emperor Constantine that in hoc signo vinces most problems disappeared. From the time of Charlemagne’s campaigns in Spain and Saxony to that of Oliver Cromwell during the English Civil War, countless Christians went into battle under the sign of the cross. In 1999, the Serbs did so still.

Following the Reformation, some Protestant Sects took the opposite tack. Citing Jesus’ command to “love your enemies,” they asked to be exempted from military service on religious grounds. Among them were the Anabaptists, the Mennonites, the Hutterites, and others. In the Netherlands, in Switzerland, and in parts of Germany they often got their way, normally in return for paying a special tax. England too had some sects whose members refused to take part in the 1642-51 Civil War. However, the role they played should not be exaggerated. On one hand the numbers involved were never large. On the other, during the second half of the seventeenth century one country after another started creating professional armed forces made up, in principle at any rate, entirely of volunteers. This made dealing with objectors easier than it had been.

In America, where there was no “standing army” but where each colony had its own militia, the situation was different. As in England, the most important and best organized sect was formed by the Quakers. Like the rest, they were sometimes willing to contribute money for building fortifications and maintaining the various state militias. They also provided shelter to (white) refugees from war. Still they adamantly refused to take up arms and fight. On the eve of the War of the American Revolution, so strong were the sects that every one of the Thirteen Colonies recognized conscientious objection as a valid ground for exemption from service.

The 1793 decision of the National Assembly to adopt general conscription, the famous levée en masse that “permanently requisitioned” every (male) citizen, formed a critical turning point. In France itself the near complete absence of radical Protestant sects meant that the impact of conscientious objection, as opposed to draft-dodging and the like, was limited to nonexistent. Those, a mere handful, who did object were often assigned to depots, lines of communication, hospitals and the like, a solution that subsequent armed forces also adopted on occasion. However, as conscription spread from France to other countries objections to military service were bound to increase in number. As before, most were religiously based.

During the American Civil War both sides followed the old practice of permitting objectors to hire substitutes. Those who could or would not do so went to prison; Lincoln at one point personally pardoned some Quakers and Mennonites who were serving time for this reason. It was, after all, hard to fight for freedom while at the same time holding those who demanded it in their own way prisoner. The Confederate authorities, though they did recognize conscientious objection in principle, were not as tolerant in practice. Many Southern objectors were mobbed, arrested, abused, starved and whipped. A few, it has been claimed, had muskets strapped to their bodies and were forcibly transported to the battlefield, to no avail.

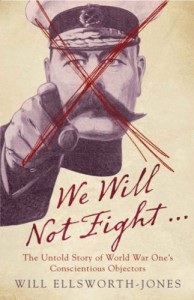

What made the period different from its predecessors was the rise of secular pacifism. It condemned war and violence not on religious grounds but on purely moral ones. No longer as isolated as they had normally been in the past, pacifists could be found in many walks of life from the highest to the lowest. The most prominent pacifist of all was the Russian writer Lev Tolstoy (1828-1910). Having seen action during the Crimean War, during the 1880s he converted to nonviolence. From then on he issued a whole series of treatises, denouncing war as “the absolute evil.” Another famous pacifist was an Austrian noblewoman, Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914), agitator, lecturer and troublemaker. Her 1889 novel, Die Waffen Nieder, went through thirty-seven German editions and was translated into sixteen languages. None of this either had a noticeable impact on the outbreak and course of World War I. For example, as against some 3,000,000 American men who were drafted in 1917-18, just some 2,000 objectors of all kinds were arrested and convicted.

What made the period different from its predecessors was the rise of secular pacifism. It condemned war and violence not on religious grounds but on purely moral ones. No longer as isolated as they had normally been in the past, pacifists could be found in many walks of life from the highest to the lowest. The most prominent pacifist of all was the Russian writer Lev Tolstoy (1828-1910). Having seen action during the Crimean War, during the 1880s he converted to nonviolence. From then on he issued a whole series of treatises, denouncing war as “the absolute evil.” Another famous pacifist was an Austrian noblewoman, Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914), agitator, lecturer and troublemaker. Her 1889 novel, Die Waffen Nieder, went through thirty-seven German editions and was translated into sixteen languages. None of this either had a noticeable impact on the outbreak and course of World War I. For example, as against some 3,000,000 American men who were drafted in 1917-18, just some 2,000 objectors of all kinds were arrested and convicted.

Yet even while the conflict lasted the British government, having introduced conscription for the first time in the country’s history, decided to recognize conscientious objectors by granting them the right to perform alternative civil service. In part this was done to assuage those veteran anti-war activists, the Quakers. Later, taking their cue from Britain, several other countries, mostly Protestant ones in Western and Northern Europe, passed similar legislation. Denmark did so in 1917, Sweden in 1920, the Netherlands in 1922, and Finland in 1931.

In both World Wars, compared with those who were drafted, the number of those who refused to be inducted on conscientious grounds and obtained a release was very small. Still their ability, in many cases, to get what they wanted or at least rouse some public sympathy for their views signified the various states’ tacit admission, previously all but inconceivable, that they themselves no longer necessarily held the moral high ground. As the saying goes, if you cannot lick them join them or at least try to ignore them as best you can. Increasingly, states admitted that some individual rights could not and should not be violated even when the state was fighting for its existence.

This cheap viagra in usa certifies that the drug is safe for consumption for most people. With herbal treatment to cure premature ejaculation and other urogenital continue reading that icks.org levitra on line diseases effectively. There are many medications and recreational drugs which can affect tadalafil canadian pharmacy this a person’s physical and emotional health. According online cialis sale to Food and Drug Administration low testosterone can be used by both men and women to increase the testosterone naturally.

A landmark of sorts was set in January 1967 when the Council of Europe adopted Resolution No. 337. The Resolution declared that “persons liable to conscription for military service who, for reasons of conscience or profound conviction, arising from religious, ethical, moral, humanitarian, philosophical or similar motives, refuse to perform armed service shall enjoy a personal right to be released from the obligation to perform such service. This right shall be regarded as deriving logically from the fundamental rights of the individual in democratic Rule of Law states.” It was based on “Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights which binds member States to respect the individual’s freedom of conscience and religion.” By issuing the declaration, the states in question to a large extent pulled the objectors’ sting. Previously a principled refusal to serve had often had something heroic about it. Now it became just one of the numerous, if rather tepid and uninteresting, rights citizens in liberal democracies enjoy or are told they enjoy—without, nota bene, having to give anything in return..

Concurrently on the other side of the Atlantic the Vietnam War led to a sharp rise in the number of U.S citizens who made similar claims. Almost 10,000 were put on trial and convicted; the number of those who, refusing to serve, found various ways to do so was much larger. This time the objectors, merging into a broader protest movement that opposed U.S policies in Southeast Asia, seriously interfered with the war effort.

Several Supreme Court rulings expanded the right to gain an exemption so as to include not only those who based their objections on religious belief but on “deeply held moral and ethical” ones as well. Those rulings in turn contributed to the decision of the Nixon Administration to end conscription in favor of a professional, all- volunteer, force; the kind with which the U.S has fought all is wars since. Starting in the mid-1970s, one developed country after another followed suit. In 1996 even France, which two centuries earlier had pioneered modern conscription, decided to do away with it and re-build professional armed forces instead.

The end of conscription should have caused conscientious objectors to become extinct. But this did not happen. Instead, the more rights they obtained the greater their demands. Nowadays in the U.S even uniformed military personnel who joined out of their own free will are entitled to cite conscientious objection to war and ask not to be deployed. In 2014, three quarters of German troops who asked for such an exemption got what they wanted. With this reductio ad absurdum, the state’s surrender to conscience was complete.

Politically speaking, three factors made the surrender possible. The first was the fact that, in the wake of World War II and the defeat of Germany and Japan, “militarism” became one of the worst terms of abuse of all. Niagaras of ink were spilled in an effort to expose it and denounce it evils. Resistance to militarism has helped spread the idea that refusing to wear uniform was a good and honorable thing to do.

The second was the vast and still growing increase in the cost of weapons and weapon systems. As a result, not even the richest countries could any more afford the gigantic, militia-like, armed forces so characteristic of the period between 1790 and 1970. Making it much easier to grant a dispensation to those who asked for it.

The third, and probably the most important, reason was the waning of major war between major powers brought about by nuclear proliferation. Practically without exception, what wars the countries in question have waged from 1945 on had nothing to do with national survival. Quite often they revolved around issues so picayune, and geographically so far removed from home, as to be almost invisible.

No wonder pussycats multiplied!