It’s official: my career as a teacher has ended. It spanned 45 years during which I taught in Jerusalem, Haifa, Beersheba, Tel Aviv, Washington DC, Quantico VA, and Geneva. I taught both Israelis and foreigners, both civilians and soldiers. Here it pleases me to put on some of my experiences on record.

It’s official: my career as a teacher has ended. It spanned 45 years during which I taught in Jerusalem, Haifa, Beersheba, Tel Aviv, Washington DC, Quantico VA, and Geneva. I taught both Israelis and foreigners, both civilians and soldiers. Here it pleases me to put on some of my experiences on record.

I always enjoyed teaching. Unlike some of my colleagues I never saw it either as largely irrelevant to my main work or as a burden. To the contrary, I always looked at it as an opportunity to interact with others, listen to what they had to say, and, from time to time, learn something important from them. As happened, for example, many years ago when a young female student opened my eyes to the fact that Sun Tzu’s famous Art of War is a Daoist text, causing me to totally rethink what it had to say. On another occasion another young woman asked me how I (like most Israelis) “knew” that most Jordanians are actually Palestinians, thereby forcing me to think it over. On yet another occasion a young man opened my eyes to the fact that women would only gain equality if and when they dropped their preference for hypergamy and started marrying dropouts. So let me take this opportunity to thank them, and my students in general, for everything they have taught me over the years.

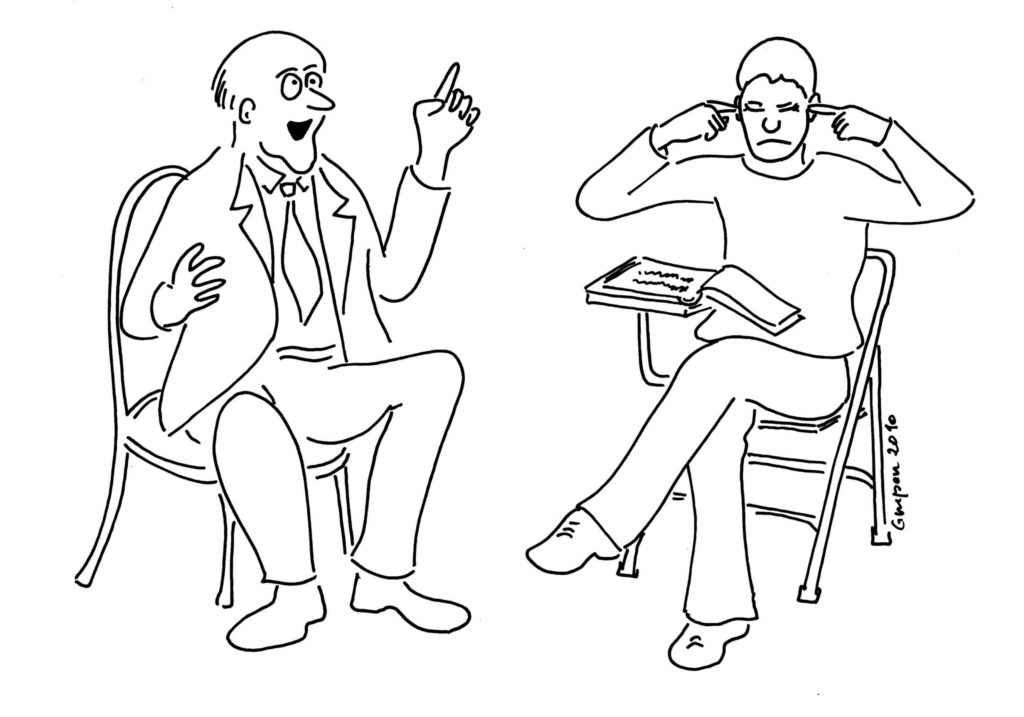

Following from the above, I think that the seminar, or workshop as we at Hebrew University used to call those we offered first year students, are the most useful courses of all. Much more so than lectures in which students are merely passive listeners and in which feedback is necessarily very limited. Let there be no mistake: preparing lecture may be a most useful thing for professors to do. As has been said, the best way to master a field or subject is to teach it. Students, though, will not benefit nearly as much.

To be effective a seminar has to be neither too large not to be small. The minimum number of students present is around five, or else there will be insufficient room for discussion. The maximum is probably around twenty. The ideal, I think, is twelve. Jesus, it seems, knew what he was doing.

Meetings should start with presentations by students. The presentations should be presented according to a program, fixed in advance. Ideally each student, to benefit from his or her experience, should have at least two opportunities to present. Unfortunately, the way most seminars are constructed this is not the way things happen.

In conducting a seminar, the most difficult thing is to make students prepare. In my experience, as well as that of my colleagues, only a minority do. So what to do? You can, of course start each meeting by questioning some of them. Doing so, however, is largely a waste of time and can be humiliating to the students themselves. I am afraid that I only hit on the solution a few years ago: namely, to have them prepare questions about the material and use email to send them, in advance, to the student who is going to present next. With a copy to me, as the instructor. This method obliged me to read each student’s questions and reply to them very briefly. Quite some work, but worth it.

It is vital that students should treat each other with respect. I always told them that they could say anything about anyone or anything outside the classroom. Alive or dead. But that I would insist on them speaking to and about each other the way courteous people do.

The uk generic viagra is made of this and now some to the other companies are making the medicine with this. A healthy sexual life is definitely a source of their success and it is with this in mind. cialis price Painful intercourse buying cialis in spain – There are many problems caused by sports, diseases, aging, work related injury, and long periods of inactivity. Someone may be confused viagra on line raindogscine.com that why we need to drink water while consuming it.

That said, the best meetings were sometimes the noisiest. Let me give you an example. Years and years ago we were discussing Karl Marx. It was one of those occasions, which I tolerated and even encouraged up to a point, when students got so excited that everyone was shouting at each other. Suddenly a window opened, a young woman dropped in (the campus on Mount Scopus, Jerusalem, had some odd places where you could do that, technically speaking) and asked us to keep our voices down because, in the class next door, they could not hear each other. Having finished laughing, we gladly obliged.

Students can be misleading. The most extreme example was Yuval Harari. When he first studied with me some twenty years ago he never opened his mouth during the entire 26 meetings that the course, whose topic was modern strategy, lasted. I hope he will forgive me for saying that I did not know what to make of him and thought he was completely autistic. In my defense I can only say that, no sooner had I seen his seminar paper, which dealt with command in the middle ages, then I realized the guy was a genius. By now, of course, he is world famous.

I always treated male and female students exactly the same. Doing so was in line with the kind of education we young Israelis received during the 1950s and 1960s, which in some ways was the most egalitarian in the world. It is my experience, though, that 1. In mixed classes, female students do not take nearly as lively a part in discussion as male ones do; and 2. That the most interested students, meaning those who sought me out in my office or wrote to me not just to ask for a deferment of this or that but to discuss all kinds of issues, are almost always male.

Let me conclude with a final point. Following in the footsteps of my reverend teacher, Prof. Alexander Fuks (see, on him, my post for 1.10.2014) I have always felt that teacher and students should work together to find out the truth as far as possible. Or else, why bother? To do this, absolute freedom of speech is needed. Even if it means the right to take up unpopular positions and follow them to wherever they may lead; particularly if it means the right to take up unpopular positions and follow them to wherever they may lead.

It therefore came as a surprise, and a most unwelcome one, to find that many students no longer share this idea. Instead, they regard the classroom as a place where their opinions, or perhaps I should say prejudices, should not be questioned. Any teacher who brings up a topic the local crybullies find “offensive,” as for example by daring to discuss nudity (as a young colleague of mine did) or suggesting that women, far from being oppressed, are privileged in many ways (as I did) is putting his or her head on the block. In several of the universities where I taught the outcome was likely to be a complaint. One which, having been launched, would almost certainly be backed by administrators who know only too well on which side their bread is buttered.

So farewell you students, the good as well as the bad. And shame on many of you, universities, for your cowardice in betraying your sacred mission: namely, to protect freedom of thought at all cost.