As a few of you may remember from my previous posts on this blog, some years ago I took an interest in the question, what things do not change. The idea was to write, not just history but a new kind of history. One that would focus, not just on change—which is what every serious historian has been doing at least since Polybius commented on how important, how utterly fascinating, change was and is—but on its absence; in other words, continuity. This project kept me busy for about eighteen months ere I realized that it was beyond my powers. So I gave up and moved to more modest projects such as I, Stalin (2022).

There things remained. Recently, however, my interest in the topic was rekindled by a book, The History of Philosophy by Oxford professor A. C. Grayling (2019). Delving into the first part, which deals with Greek philosophy, I quickly realized that I had been barking up the wrong tree. Burying my nose in search of things that have remained the same always I had overlooked the fact that the most important continuities were not to be found in the answers the ancient philosophers came up with. Instead, they consisted of the methods they used—a combination of observation with rational inquiry, without any resort to the supernatural—and, above all, the questions they asked. Questions which, originating in pre-classical Greece, keep preoccupying people right down to the present day.

So follow a few examples of the very different questions in question. Here presented in a more or less chronological, much simplified, fairly non-repetitive way. And with hardly any more detailed exploration of their background, meaning, implications, or the links among them.

Thales of Miletus (ca. 666-585 BCE)

What is the primeval thing, or material, of which all others are made and into which they will ultimately revert?

What is the origin of movement (in other words: what and who was the earliest prime mover)?

Observation teaches us that only animate things can grow on their own accord. Does that mean plants have souls?

Does the universe, or kosmos have limits, or does it go on indefinitely?

Anaximander (ca. 610-546 BCE)

Is the observable kosmos the only one, or just one of many?

Is there a single principle that governs the observable changes in the kosmos, both in the heavens and here on earth, and, if so, what is it?

Are those changes cyclical or linear? If the latter, will they go on forever, or will they come to an end?

Anaximenes (?-526 BCE)

How to predict earthquakes?

Pythagoras (570-495 BCE)

Does the soul perish with the body, or does it persist? Is there such a thing as reincarnation?

How does the kosmos relate to numbers and mathematics, and why?

Xenophanes (570-478 BCE)

Are there gods (or is there a god) and, if so what are they?

How are the gods/god related to observable reality? Did they create it, or are they part of it?

What is time? Does it really exist, or is it merely something we experience? Will it go on forever, or does it have a beginning and an end?

Heraclitus (540-ca. 480 BCE)

How are change and continuity related to each other (the original question I was hoping to answer)?

Parmenides (515-after 450 BCE)

What is true knowledge?

Is there an infallible method for obtaining true knowledge about the kosmos and everything inside it that will prevent us from being misled by opinion, or belief, or our own senses (all philosophers from antiquity down to the present day)?

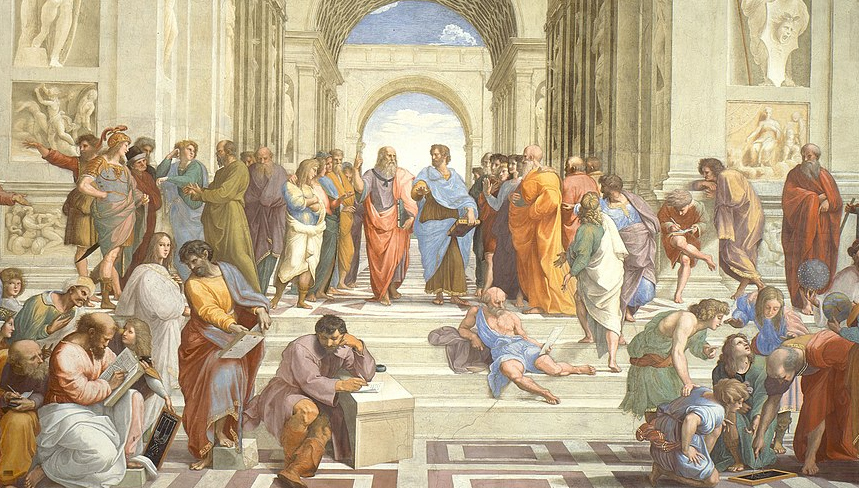

Antisthenes (466-366 BCE) Socrates 470-399 BCE), Plato (424-348 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE

What is virtue, and how can it be attained?

What is happiness, and how can be attained?

What is a good society and how can it be built and made to last?

How do/should individual and society relate to each other?

What is beauty? Does such a thing as beauty really exist, or is it only present in the viewer’s mind? (especially Plato and Aristotle)?

How did the myriad things that comprise physical reality come into being, and how do they function and interact (Aristotle)?

Does such a thing as the future exist, or is it a figment of the imagination (Aristotle)?

Does such a thing as the afterlife exist and, if so, what is it like (especially Plato)?

Democritus (ca. 460-370 BCE)

What is matter made of?

Does it consist of a multitude of almost infinitely small, indivisible particles, or is it continuous?

How are dead matter and mind related?

Diogenes (ca. 400-323 BCE), Crates (365-285 BCE) and Epicurus (341-270 BC)

What kind of life is the best and most appropriate (oikeion) for a human being?

Is there such a thing as the free will?

Do universals (e.g. “redness” or “catness”) really exist, as Plato says, or are only particular things real?

What is the purpose of philosophy?

Zeno (334-262 BCE) and the Stoics

Is there such a thing as fate? If so, what is it and how does it operate?

What is the best way to cope with the hardships of life, such as illness or disaster?

To Conclude –

As my mother, quoting an old proverb, used to say, a single fool can ask more questions than ten wise people can answer. That is true; but it is also true that Thales, Anaximander and the rest were anything but fools. Certainly it is true that, without questions, finding answers is impossible to begin with. Which is why, over two millennia later, we still keep thinking about them.

Day by day.