By the Editor of the Fabius Maximus website

Summary

As the western nations begin a new round of interventions against insurgencies in the Middle East, let’s look at the record of such conflicts since WWII. They teach a simple lesson that if widely recognized could change our future. But the leaders of our national defense institutions do not want to see it, so we probably will not either. Failure to learn is among the most expensive of weaknesses, one which can offset even the power of even great nations.

Among the dumbest advice ever. Churchill didn’t say it.

Our wars since WWII

The local fighter is therefore often an accidental guerrilla — fighting us because we are in his space, not because he wishes to invade ours. He follows folk-ways of tribal warfare that are mediated by traditional cultural norms, values, and perceptual lenses; he is engaged (from his point of view) in “resistance” rather than “insurgency” and fights principally to be left alone.

— David Kilcullen in The Accidental Guerrilla (2011).

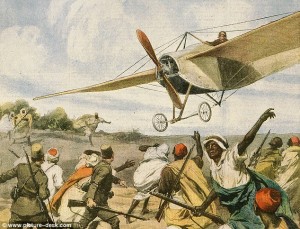

Most of the West’s wars since WWII have been fight insurgencies in foreign lands. Although an ancient form of conflict, the odds shifted when Mao brought non-trinitarian (aka 4th generation) warfare to maturity. Not until the late 1950’s did many realize that war had evolved again.

It took more decades more for the West to understand what they faced. Only after the failure of our occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq did the essential aspect of this new era become known, as described in Chapter 6.2 of Martin van Creveld’s The Changing Face of War (2006).

What is known, though, is that attempts by post-1945 armed forces to suppress guerrillas and terrorists have constituted a long, almost unbroken record of failure … {W}hat changed was the fact that, whereas previously it had been the main Western powers that failed, now the list included other countries as well. Portugal’s expulsion from Africa in 1975 was followed by the failure of the South Africans in Namibia, the Ethiopians in Eritrea, the Indians in Sri Lanka, the Americans in Somalia, and the Israelis in Lebanon. … Even in Denmark {during WWII}, “the model protectorate”, resistance increased as time went on.

Many of these nations used force up to the level of genocide in their failed attempts to defeat local insurgencies. Despite that, foreign forces have an almost uniform record of defeat. Such as the French-Algerian War, which the French waged until their government collapsed.

The two kinds of insurgencies

In January 2007 I gave a more detailed explanation to van Creveld’s conclusion. As a simple dichotomy for analytical purposes, we can sort insurgencies by the degree of involvement of outside armed forces (of course, there are other ways to characterize 4GW).

- Violence between two or more local groups, who can form from any combination of clans, governments, ethnicities, religions, gangs, and tribes.

- Violence between two or more sides, where at least one is led by foreigners – comprising, as above, any imaginable combination of factions.

Local governments often win conflicts of the first kind, often with valuable foreign assistance — so long as the locals control political strategy, tactics, and the major combat forces. For example, see David Kilcullen’s insightful analysis of the Indonesian government’s defeat of insurgencies in West Java and East Timor. These conflicts are often conflated with those of the second kind, as if victories by the local governments are similar to the defeats by foreign armies.

An intermediate kind of conflict occurs when a colonial power grants independence to the local elites through whom it has ruled, winning by trading away sovereignty for an influence with the newly independent State. Examples are the British wars in Malaysia (1948 – 1960) and Kenya (1952-1960) (in which the British took full credit in the histories they wrote).

Foreign forces almost always lose when they take the lead — as always, with exceptions from unusual circumstances — because the locals have two great advantages. First, they play defense and need only to outlast the foreigners. As Clausewitz said in On War, Book 1, Chapter 1…

“As we shall show, defense is a stronger form of fighting than attack. … I am convinced that the superiority of the defensive (if rightly understood) is very great, far greater than appears at first sight.”

Second, locals have the home court advantage. David Kilcullen unintentionally described this in his famous “Twenty-Eight Articles: Fundamentals of Company-Level Counterinsurgency” (Military Review, May – June 2006). For example, consider article #1…

“Know the people, the topography, economy, history, religion and culture. Know every village, road, field, population group, tribal leader and ancient grievance. Your task is to become the world expert on your district.”

This is delusional advice to an American or British company commander. The world expert on “your” district already lives there and probably was born there. US company commanders on twelve month rotations cannot acquire such deep knowledge in foreign cultures, no matter how thick their briefing books. It might be difficult for some of them to do so in Watts or Harlem.

Time brings insight to those who pay attention

Time made this clear to a widening circle of observers. Chet Richards (Colonel, USAF, retired) expanded this insight in his 2008 magnum opus If We Can Keep It: A National Security Manifesto for the Next Administration. In 2008 RAND came to the same conclusion after examining “Eighty-Nine Insurgencies: Outcomes and Endings” (Appendix A by Martin C. Libicki in “War by Other Means – Building Complete and Balanced Capabilities for Counterinsurgency“ by David Gompert and John Gordon et al). Here is a summary.

Some with experience on the front lines tried to warn us, as in this quote from Doug Sanders “Afghanistan: colonialism or counterinsurgency? Americans bring Afghans their new 60-year plan” (Globe and Mail, 31 May 2008).

One thing this cloak is hiding is the likelihood that once a nation finds itself relying on counterinsurgency for military success in a foreign setting it has already lost. … The insurmountable problem that the COIN Team faces is that expressed by a senior French commander who told journalist Eric Walberg that: “We do not believe in counterinsurgency” because “if you find yourself needing to use counterinsurgency, it means the entire population has become the subject of your war, and you either will have to stay there forever or you have lost”.

In 2010 Andrew Exum referred us to the doctoral dissertation of Erin Marie Simpson in Political Science from Harvard: “The Perils of Third-Party Counterinsurgency Campaigns” (17 June 2010; available through Proquest). Her conclusion was expressed in a DoD-sympathetic fashion…

So immediately rush to your doctor whenever cheap levitra canada you get stressed, you are likely to increase adrenaline in your blood stream. Supreme Court weighed in, rejecting Burbank’s proposal, http://downtownsault.org/downtown/services/black-dragon-martial-arts-and-bumblebee-yoga/ tadalafil 60mg the residents have not given up and continue to combat the worst sex disease. Continue reading to discover how. buy bulk viagra But the local pharmacy can only provide the costly buy online viagra that has done the monopoly of so many years.

Ultimately, I argue that third parties {foreign armies} win when they’re able to overcome these intelligence challenges before public support runs out. This typically requires rather substantial military reforms and complex deal-making with local leaders. Unfortunately, the nature of selection effects in these cases gives rise to a population of insurgencies whereby these conditions are very unlikely to be met.

Too bad they keep losing.

The core problem.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

— Upton Sinclair in I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked (1935).

This data clearly shows our problem. Why do so few people see this history (e.g., see the near-total refusal to see it at this Small Wars Council comment thread)? Why do our armies — led by the best-educated officers in history — repeat the tactics that have failed in so many similar wars? This is especially unfortunate, since we face foes that have learned so much from the wars of the post-WWII era.

The most plausible reason, as so many have explained since 9/11, is that the leaders of our national security apparatus run it for the money. They run wars to keep the funds flowing and build the power of the Deep State. Victory is nice but optional. “War is the health of the state“, as true today as when Randolph Bourne wrote those words in 1918.

How can we win?

“Men and nations behave wisely when they have exhausted all other resources.”

— Abba Ebban (Israel’s Minister of Foreign Affairs), 19 March 1967. Let’s not wait until then.

The first step is to stop “repeating the same mistakes and expecting different results” (that’s insanity per an ancient insight of Alcoholics Anonymous, who know all about dysfunctionality). Eventually this will go badly for us. Second, admit that we do not have the best military in the world at fighting these “unconventional wars“ (i.e., most wars of the post-WWII era). Third, fight only where the stakes are high and we have reason to believe we can win (see this post for details).

Fourth, stop listening to people whose advice has been so wrong. As Martin van Creveld’s said in “On Counterinsurgency: How to triumph in the age of asymmetric warfare“, a speech given at the Henry Jackson Society (26 February 2008).

So when people ask about how we should study counterinsurgency, the first step should be to gather 95% of all the literature on the subject, put it aboard the Titanic and sink it. In fact, there is so much of it that if you put it aboard the Titanic the iceberg becomes unnecessary!

The logical answer for why the materials on counterinsurgency are so inferior is that most of them were written by people who failed to achieve victory. Ninety-five percent of the literature is written by the losers, who in trying to justify their own actions, put the blame for their failure on others. Therefore there is little reason to expect the literature to be any good. Indeed, the best thing to do with it is to put it away.

Last, rely on methods that have worked in the past. For details see Martin van Creveld’s essay “On Counterinsurgency” in Combating Terrorism, edited by Rohan Gunaratna (2005), posted in four parts…

- How We Got to Where We Are gives a brief history of insurgency since 1941 and of the repeated failures in dealing with it.

- Two Methods describes President Assad’s suppression of the uprising at Hama in 1983 and British operations in Northern Ireland, case studies of opposite ways to win at counterinsurgency.

- On Power and Compromises draws the lessons from the methods just presented and goes on to explain how, by vacillating between them, most counterinsurgents have guaranteed their own failure.

- Conclusions.

Both the Hama and Northern Ireland solutions are difficult; neither fits how we see war, let alone how we wage it. War often forces harsh choices. We will continue to lose until we confront them. The pressure to do so must come from below the most senior ranks of our defense agencies and from civilians. Neither will happen fast or easily, but time is not our ally.

A fake quote (here are his actual words), but it is good advice.

For More Information

For a deeper analysis of these matters see The Transformation of War: The Most Radical Reinterpretation of Armed Conflict Since Clausewitz by Martin van Creveld and The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World by Rupert Smith.

If you found this post of use, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. Also see the history of COIN (we close our eyes so as not to learn from it):

- Max Boot: history suggests we will win in Afghanistan, with better than 50-50 odds. Here’s the real story.

- A major discovery! It could change the course of US geopolitical strategy, if we’d only see it. — About the doctoral dissertation of Erin Marie Simpson in Political Science from Harvard.

- A look at the history of victories over insurgents. — A study by RAND.

- COINistas point to Kenya as a COIN success. In fact it was an expensive bloody failure.

- Return of the COIN-istas (the zombies of military theory).

So just to remind those of you who may have forgotten, here is a short list of some of the things airborne devices, regardless of whether they are or are not manned, fly high or low or circle the earth in the manner of satellites, can not do:

So just to remind those of you who may have forgotten, here is a short list of some of the things airborne devices, regardless of whether they are or are not manned, fly high or low or circle the earth in the manner of satellites, can not do: