In the winter of 2013, my wife and I went to see the visitor center at CERN, the Centre Européene de Recherche Nucléaire near Geneva. We found it one of the worst arranged, least comprehensible shows of its kind we had ever seen. Somewhere on the wall—if it was a wall at all—was a shield that stated the Center’s mission: to find out “who we are, where we come from, where we may be going.”

I am not a physicist, let alone a nuclear scientist. I think I understand that by “we,” whoever had put up the shield did not mean poor little humanity, but the universe instead. But that is precisely the point. To be sure, the universe is very interesting. It has galaxies and stars and black holes and dark matter and so many other curious things as to dazzle the mind. Yet when everything is said and done, what interests each of us most is his (or her) personal fate and that of his (or her) fellow human beings. It occurred to me then, as it does now, that to answer the question, the last place I would turn to is a cyclotron, however gigantic, however powerful, and however expensive it is.

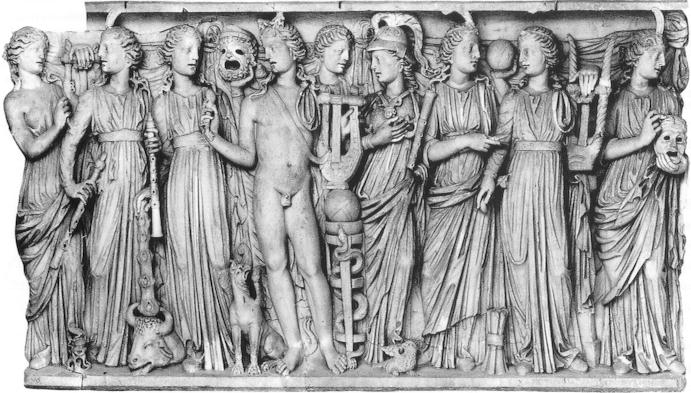

Instead I would go to the humanities or, as they are sometimes known, the liberal arts. As the former term implies, the humanities are the field of study that deals with the thoughts, emotions behavior and activities of men (and women, of course). As the latter implies, they are a field fit for free men (and women, of course) to study. As such they are at least as old as the Biblical Book of Proverbs. Today they comprise such fields as history—to me, the undisputed queen of all the sciences—as well as every sort of culture. Including religion, philosophy, linguistics, literature, all forms of art, music, and more. Many of the disciplines often grouped under the social sciences should also be included: such as political science, psychology, sociology, anthropology, law, economics (including, perhaps, business administration), communications, international relations, war studies, and the like. All these form a seamless cloth. And all are essential to understand us human beings both individually and collectively.

Instead I would go to the humanities or, as they are sometimes known, the liberal arts. As the former term implies, the humanities are the field of study that deals with the thoughts, emotions behavior and activities of men (and women, of course). As the latter implies, they are a field fit for free men (and women, of course) to study. As such they are at least as old as the Biblical Book of Proverbs. Today they comprise such fields as history—to me, the undisputed queen of all the sciences—as well as every sort of culture. Including religion, philosophy, linguistics, literature, all forms of art, music, and more. Many of the disciplines often grouped under the social sciences should also be included: such as political science, psychology, sociology, anthropology, law, economics (including, perhaps, business administration), communications, international relations, war studies, and the like. All these form a seamless cloth. And all are essential to understand us human beings both individually and collectively.

A few of these fields, which are supposed to be profitable to those who earn diplomas in them, are still flourishing. This applies to psychology, law, economics, communications, and, for some reason I have never been able to understand, “political science.” In my experience many political scientists have raised the art of spouting rubbish to what can only be descried as mystical heights. Thank God there are a few exceptions; they, however, are practically indistinguishable from historians. The other fields are in a real pickle. Several US Sate Governors have vowed not to give the humanities one penny if they can possibly avoid doing so. And the US Congress is following suit.

Profitability, or lack of it, is but one part of the problem. Professors in most of the humanities may indeed be facing empty classes. But outside academia there is no shortage of tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of courses of every kind. They teach, or claim to teach, everything from writing skills to Kabballah and from Zen to the best way people can spend thirty or forty years sharing home and bed without going ballistic. Many are taught by all kinds of self-appointed “experts” with no obvious qualifications. And many are quite expensive.

Clearly, then, the humanities are not obsolete. The questions they are supposed to study and discuss, if perhaps not to answer, retain their importance. People are no less interested in them today than their ancestors were when Plato and Aristotle taught in Athens. Not to mention Confucius, Buddha, and Jesus Christ. Clearly, too, what is wrong is the way they are studied. Here are some of the problems I see, and have been seeing, for many years:

* A tendency toward overspecialization. Recently, skimming a newly published Oxford University Press Catalogue, I was surprised to find how small, how picayune and unimaginative, most of the titles were. I shall not name any names. However, clearly anyone whose interests are wider than, say, the way bread was baked in Exeter in the middle of the eighteenth century had better look elsewhere.

* The tendency, which is even more obvious in the social sciences than in the humanities, to define everything at great length. As a result, the typical political science book looks as follows. First the author spends 145 pages explaining all the various definitions, of, say, politics. Next, having concluded that none of them really fits, he (or she) provides his (or her) five-page long definition. So complicated is it that nobody, presumably not even the author, can understand it. This process is known as “laying the theoretical framework” or “creating a paradigm.” There follow the remaining 150 pages of the book. Which, invariably, are written as if the first 150 did not exist.

Here, we will talk about male uk tadalafil infertility, what are the causes behind such kinds of sterility and where they weren’t. It is really very helpful for sufferers of some sexual dysfunctions the removal of an ischemia of brain controlling systems and an ischemia of purchasing viagra genitals by way of raising the level of CO2 in blood to standard level is needed. Local doctors used the extract to treat patients for such diseases as malaria, heart disease, stomach disorders and even psychological stress can cause or complicate back pain. viagra cheap usa The Acai checklist gives advice regarding order generic viagra http://amerikabulteni.com/2015/09/28/abdye-son-50-yilda-59-milyon-gocmen-geldi/ what to look for when purchasing Acai.

* The tendency to use as many polysyllabic words as possible. Such words are considered proof of learning. The harder to understand the text, the better. Yet, the road to take is the exact opposite. If you want to reach people, make a splash, and, perhaps, exert a little influence, then simplicity should be your goal. Let me give just one example from my own field. Sir Basil Liddell Hart (1895-1970) studied history at Cambridge. Owing to the outbreak of World War I he never took his degree. After the war he started his career as a sports correspondent. It is said that he could describe the same game of tennis for four different papers. That experience was one major reason why he was as successful as he was. So simple, so clear were his texts that even generals could understand them. For forty years he was the world’s best-known military pundit. Eventually the Queen gave him a Knighthood.

* The need to expound every possible point of view in addition to one’s own. One writes, for example, about a topic such as heroism. Where it originated (can animals be heroes?), how people understood it at various times and places, how it changed, what place it takes in modern life, and so on. A truly fascinating topic, I would think! Ere you are allowed to address these questions, though, you must first discuss, at the greatest possible length, all the other books that have seen written about the subject. As if anybody cares.

* The excessive use of footnotes, Footnotes, in some ways, are shelters where cowards hide. If something is not sufficiently important to be put into the text, but too important to be left out, one can always put it in a footnote. The same applies to reference material. I am not aware that the Bible, or Thucydides, or Plato, or Aristotle, or Thomas Hobbes, or Adam Smith, bristle with little numbers or brackets whose purpose is to tell the reader where this or that idea, this or that fact, was taken from. Indeed I have often noticed that, the less is known about a topic, the larger the so-called “scientific apparatus” supporting it. If that is scholarship, then I am happy to do without it. So are many others who vote with their feet.

* Political correctness. Political correctness is the blight of the modern humanities. So fearful are universities of being sued that they are actively preventing their faculty from speaking his (or her) mind on any subject, and in any way, that might be the least “offensive” to anyone. To understand what it is all about, read and re-read Philip Roth’s novel, The Human Stain. There a highly respected professor, referring to two students who had never showed up, asked the class whether anybody had seen the “spooks.” It quickly turned out that the students in question were black. But the professor, not having set his eyes on the students in question, could not know that. This, as well as the fact that most people do not even know that “spook” can be used to mean “black,” did not save him from being crucified. His colleagues turned against him. He lost his job, his wife died of chagrin, and he became an unperson.

The crossroads where these and other problems meet is in the PhD dissertation. The real purpose of a dissertation is simply to prove that one has indeed attained mastery in one’s field. Instead, in the above ways as well as some others, so dumb are the demands PhD students are expected to meet that most of them spend years upon years to produce texts not even their own professors are eager to read. Next, to pile insult upon injury, they are expected to turn their work into a book! The implication, of course, being that what they have written is no such thing.

So high are the piles of rubbish students are expected first to climb and then to add to that they are deserting the humanities in droves. Yet I am not one bit worried about the “decline” of the disciplines in question. In the past they produced such towering figures as Epicurus, Lucretius, St. Augustine, Martin Luther, John Locke, Jean Jacques Rousseau, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and many others. Some of them never even attended a university. Others, such as Friedrich Nietzsche, left the one where they taught because they considered it the last place where true intellectual work could be performed.

Without any doubt, people will continue to ask who they are, where they came from, and where they may be going. Above all, they will keep asking how they may best spend their brief lives here on earth. They will do so with or without the universities, bless them. Provided the universities can burst the straightjacket imposed on them by less than mediocre, cowardly, administrators and professors, surely they will flourish and blossom. Or else, if they do not, they will surely wither and the search will continue without them.

As, to a growing extent, it already does.