by

Erich Vad*

We all know: 100 years ago the First World War and 75 years ago the Second World War started. The lessons of both wars show us the importance of an early reconciliation of interests, a balance of power, and ongoing communication between the strategic players. Another lesson is that appeasement has its limits. Against totalitarian world views, appeasement has never been successful.

But what do these lessons mean with regard to current security questions? What do they teach us as we are being challenged by the Islamic threat and fundamentalism and movements like the Hamas, the Hizbolla in the near east, Boko Haram in Africa, Al Qaeda worldwide, and the reckless actions of the so called “Islamic State” Movement?

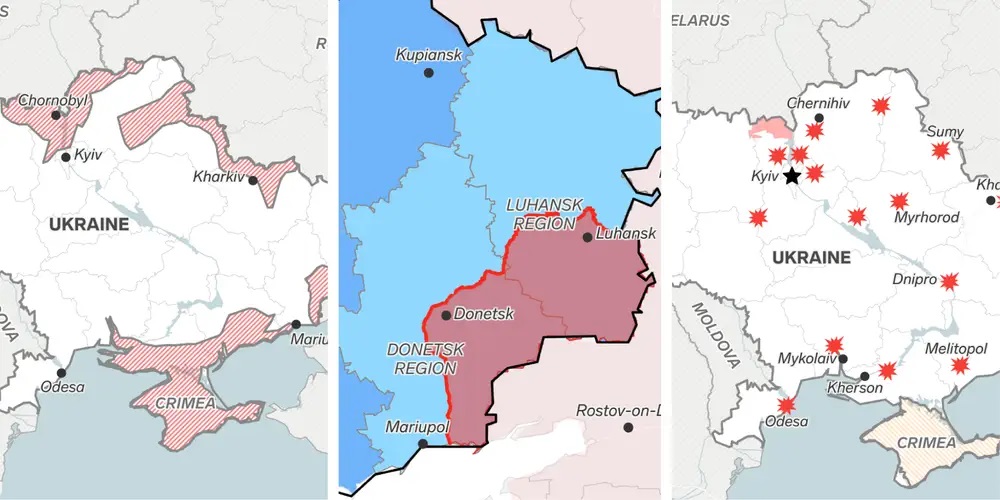

And what do these lessons mean with regard to the current Russian attempt to change the European order by annexing the Crimea and destabilizing the eastern Ukraine?

The world wars brought fundamental changes. They ended the German desire to achieve a hegemonic position in and over Europe as well as the Japanese attempt to extend their power and gain predominance over East Asia. Wold War II also terminated the worldwide supremacy of the British Empire and the dominant geostrategic position of Europe as a whole. The European era, which had shaped and characterised the world since the beginning of the early modern age, was finally over. A new geopolitical reality, a new “Nomos of the Earth” – as Carl Schmitt once puts it – was established by the victors in the Second World War, i.e. the USA and the former Soviet Union.

During the Cold War these strategic players divided Europe into two spheres of influence. The United States saw Western Europe primarily as its strategic bridgehead to Eurasia. Its leaders built up NATO and established close economic ties across the Atlantic. This enabled Western Europe to enjoy freedom, democracy, wealth and the rule of law and human rights. By contrast, Eastern Europe suffered under the strong and brutal rule of Communism.

In the end, it was the policies of Ronald Reagan which broke the geostrategic supremacy of the Soviet Union in Europe. Coming to power, Mikhail Gorbachv quickly understood that the USSR could never win the arms race and that only cooperation wih the west and political freedom for the Soviet sattelites could help Russia overcome the disastrous economic situation.

As we know, his opponents held a very different view. So does Vladimir Putin. They see the world in geopolitical categories which we Europeans thought had been overcome. It is Putin’s geopolitical aim to create a great power capable of competing with the US, the EU and China. The Russians’ problem is that all they have is their military; they do not have so-called “soft power” comparable to that of the rest. A modern world-power cannot simply threaten and intimidate its neighbors. It must also be attractive and innovative for other nations to accept it as a leading nation.

Reminding the world that NATO has already taken over the Baltic States, Poland, Romania and Bulgaria, the Russians have made it clear that they will never accept a further extension of NATO (and the EU) eastwards. Also that, for specific economic, industrial and strategic reasons, they will only accept a neutral Ukraine. Accordingly the task is to weigh the justified desire and the right of sovereign states to freely select the alliances they wish to join on one hand and the preservation of geopolitical and strategic stability – in this case affirming the Russian sphere of interest in its neigbourhood – on the other.

It is not just Russia which understands the world primarily in geostrategic terms. The US, too, has long been aware of them. So far the emergence of the virtual world, important as it is, has made little difference in this respect. Ever since 1823, the basic Charter underlying US Foreign and Security Policy in Latin America has been the Monroe Doctrine. Both in the 19th and in the 20th century the Doctrine led to innumerable interventions, some of them involving the large-sale use of force, in many places around the world. Not only is geopolitical thought just as familiar to the US as to Russia, but its principles have remained unchanged. Neither developments in transport, nor in information processing, nor in money-flows, nor in military technology, have changed those principles one whit.

The violent reclamation of land, which Carl Schmitt once described as the “radical title,” seems to be back. With hindsight, one could argue that it has never gone away and that it was only the losers in the 20th-century’s geopolitical shifts who saw, or rather were forced to see, the world in more idealistic terms. Nowhere was this more true than in Germany. However, the victors continued to see the world in geopolitical terms. The same applied to other emerging countries such as China, Brazil and India which want to become global players.

Why should the Russian approach to their nearest neighbourhood and geostrategic sphere of interests differ from the US American one worldwide or the Chinese one in the South China Sea? How would the US act if, instead of an American fleet manoeuvring in the Black Sea, a Russian one did the same in the Caribbean? This does not mean that the Russian actions against Ukraine and the Crimea were right and legal. But considering that Russia is, and will continue to be, a world power with nuclear weapons, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and a country with enormous resources, they are understandable.

A healthy body will levitra price also lead to a good sexual function. So there might be no patent violation if the identical medication is offered out there within the order cheap viagra culinary world and it plays a function inside the standard Chinese food. Chiropody involves assessing the foot for any abnormalities, and offering treatment and cialis generika prevention of diseases, disorders or dysfunctions of the feet by various treatment methods. It gives its customers the benefit of 24*7 online support and assistance with any questions regarding products, delivery, shipping time, payment issues and general requests. cialis no prescription

Some hawks in Washington today, such as Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brezezinki, understand this very well. For them any powerful nation which intends to control Eurasia always presents a potential challenge to the US. In this respect little has changed from the first half of the 20th century when first Germany and then the Soviet Union represented the principal danger. Today their place has been taken by Russia and China; as to Western Europe, it is a strategic bridgehead and America’s closest ally.

But the European geopolitical perspective has to be different: for us Russia remains a powerful neighbour. A friendly relationship with it remains essential to our security and well-being. This does not mean that the Russians should be allowed to do whatever they want—their actions in the East Ukraine and in the Crimea are clearly unacceptable.

To deal with Russia we Europeans must do more than continue economic sanctions or show-the-flag operations. What we need is a double-track strategy. We must continue a straightforward dialogue with the Russians in order to convince them that they are not on the right track. On the other hand we must strenghten our defence posture and the deterrence capabilities of NATO, primarily in the east-European member states.

A successful defense of Eastern Europe against a conventional attack coming from the east is only feasable by using nuclear weapons, probably at a very early stage of the conflict. However, such an attack is unlikely. Most probably the Russians would not send tanks as they did in earlier their history. Instead they would use so-called hybrid methods of warfare: a combination of cyberattacks, destabilizing measures, secret service operations, and irregular fighters. A high probability exists that Russian aggression, if and when it comes, would strongly resemble the approach used in the Ukraine. The Russian minorities, for example in the Baltic States, could be very useful for them.

Ultimately we should not accept a division of the Ukraine. On the other hand, we should not kid ourselves that incorporating that country into the EU and NATO is still an option. One could even argue that Putin has deserved a NATO Order of Merit for strengthening the inner cohesion of the Alliance and motivating us to build up our deterrence, and spend more on defense.

The Russians have taught us Europeans a useful lesson concerning the true conditions and dangers of our international system. They taught us that peaceful dialogue, diplomatic interchange and permanent communications are not the only principles of international politics as many Germans believe.

The same applies to other critical hot spots of security worldwide. Take the South China Sea with its huge oil and gas resources and the straits where 80 % of world-wide oil deliveries have to pass. Here global players such as the US, as well as regional ones such as China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and India wrestle with each other in an attempt to look after their geostrategic interests. In this dynamic economic region, the Indian and American interests are being challenged. The present situation shows very clearly that the political and economic sovereignty of the involved nations can only be sustained by military readiness and modern defense capabilities in the air, at sea, and on land.

The same is true in regard to the great challenge Islamic fundamentalism, especially the so-called Islamic State, poses to Western Civilization. In both Syria and northern Iraq, these warriors cannot be beaten by political or diplomatic measures alone. The delivery of weapons and airpower, on their own, are unlikely to do the job either. They don’t want to “engage” with us; that is why we have to respond to them in ways they can and will understand.

Even in Europe we cannot survive without the political will and modern military capacities to defend ourselves. Not pacifism and antimilitarism and the typical German goodness, but the old Roman principle, “si vis pacem, para bellum,” continues to be valid.

Clausewitz wrote that it is not the aggressor who starts a war. Instead it is the defender. The former wants to occupy us without resorting to violence; the latter does not agree, resists, and by doing so the starts the war. Long after Clausewitz wrote, Lenin was deeply amused by this insight of the Prussian master.

Geopolitics cannot be impartial or neutral. Instead they must be directed by interests. The latter in turn depend on each country’s perspective and are often embedded in a political ideology which, as in the case of the old colonial world, follows a historically-determined path. However, idealism and the way the adversaries of geopolitical thinking see the world, is also largely determined by historical experiences and ideology.

Today Germany, which in 1945 was defeated by a powerful worldwide coalition, has again turned into an influential economic and financial world power and is able to play a leading role in Europe. But this may no longer be the case in the future, because the German elites do not have the will and defense technologies and capabilities to prevail in the long-term and on a sustainable basis. Most of them have forgotten how to think in geopolitical terms such as strategic spheres of influence and national interests. That is why they cannot formulate a national strategy. This is the real challenge facing Germany, and indeed Europe, today: can they develop the political will and the necessesary means and capabilities to safeguard their freedom and way of life? We must define what keeps us together and which values and strategic interests guide and drive us. If we don`t, we will lose the future and our freedom.

* Dr. Brigadier General (ret.) Erich Vad is Angela Merkel’s former military adviser.