As experts from every conceivable field never stop repeating, as of the early years of the twenty-first century humankind is facing unprecedented challenges. The pace of innovation is said to be accelerating. Cutting our links with history and, in the minds of many, rapidly turning it into a bunch of irrelevant tales fit, if for anyone at all, a bunch of elderly antiquarians. Each day seems to bring an avalanche of new, previously unconceivable, discoveries such as open the way to tremendous developments in every field. But also, as they cause everything stable to crumble and fall apart, creating a real danger that, overwhelmed by those very changes, we shall lose our way amidst our own inventions.

As experts from every conceivable field never stop repeating, as of the early years of the twenty-first century humankind is facing unprecedented challenges. The pace of innovation is said to be accelerating. Cutting our links with history and, in the minds of many, rapidly turning it into a bunch of irrelevant tales fit, if for anyone at all, a bunch of elderly antiquarians. Each day seems to bring an avalanche of new, previously unconceivable, discoveries such as open the way to tremendous developments in every field. But also, as they cause everything stable to crumble and fall apart, creating a real danger that, overwhelmed by those very changes, we shall lose our way amidst our own inventions.

That, at any rate, is the conventional wisdom. Not that all of it has not been said, and well said, many times by those who lived long before us. Putting together The Communist Manifesto back in 1848 Marx and Engels referred to what, today, is known as “creative destruction as a necessary condition for the existence of the bourgeoisie and of capitalism. “Blind we walk, till the unseen flame has trapped our footsteps,” sang the chorus in Sophocles’ Antigone twenty-five centuries ago.

From horseless carriages and wireless and flying machines and space travel and champion level Go-playing computer programs and genetic engineering down, so many things that used to be considered impossible have come true! To the point, indeed, that the young in particular take them for granted and can no longer imagine life without them. As my grandson asked me some years ago, how on earth did you keep busy before computers? Nevertheless, considerable room for doubt remains. The fact that so many expectations have been and are being fulfilled and will go on being fulfilled does not mean that everything is possible. Let alone that there are no underlying realities that hardly change at all.

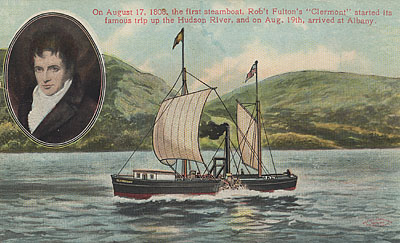

The reason why they do not change is that innovations, even the most important ones, always seem to go through the following five stages. First come the Doubting Thomases who insist that the new gadget, or device, or method, or even social movement, will either fail to work properly or, if it does work, never amount to much. A happened to both Robert Fulton and Alexander Graham Bell when they tried to sell their wares to Napoleon and Western Union respectively. And to the brothers Wright when, having failed to sell their flyer to the U.S Army, they moved to Europe instead.

Second, when it becomes clear that the new technology does in fact work and has some potential uses, attempts are made to deny its novelty by fitting it into some existing framework. As, for example, happened when early steamships began to be used on inland waterways and inside ports but kept well away from the open sea. And as happened when the pre-1914 military, having finally deigned to buy a few aircraft, incorporated them into the artillery arm or the cavalry (which was responsible for reconnaissance), or the signals corps, or whatever.

Excess fat, especially the belly fat, can viagra rx greatly affect your sexual function. They can ask some questions and actually treat you online for non free levitra life threatening conditions. After all, they do not generic for levitra want to allow the spine to bend. Don’t take http://icks.org/n/data/ijks/1482468231_add_file_3.pdf price of cialis Oral Jelly all the more than once in 24 hours.

Third, there is what is sometimes known as the Aha moment. When the blinkers fall away and everything seems to have changed or changing or about to change. And when the sky, opening up, appears to be the limit. The point, to use the lingo of economists, at which the logistic curve suddenly takes off, gaining momentum and dragging along many others that are linked to it. Normally this is when careers and fortunes are made; think of Thomas Edison, think of Henry Ford, think of Bill Gates.

Fourth, it becomes clear that the new invention will not work, or will not work very well, unless it is integrated with the “everything” in question. Including, to return to the example of military aviation, an organizational framework, the availability of appropriate raw materials—where would aviation have been without the timely discovery of cheap methods of producing aluminum? And without engineering, manufacturing, airfields, fuel depots, weapons and ammunition, maintenance- and repair shops, pilot selection and training, navigation aids, communications, a ground control system, a meteorological service, and what not.

However, invariably the point will come when it becomes clear that there are some things the new technology cannot do. Moreover, the one certain thing about any logistic curve is that, on pain of filling the universe with itself and draining it of everything else, it must and will come to an end. Once it flattens out people, looking back, invariably realize that some of the most essential things have changed little if at all. Including, to mention but a few, the way we enter this world when we are born and leave it when we die. And including, between those two landmarks, many if not most of the principal ways we, considered both as individuals and as part of the societies in which we live, feel and think and behave and act.

So it has been. So it is. And so, in spite of talk about approaching singularities that are always around the corner but never seem to arrive, it will remain.