At the time he arrived in Zanzibar in March 1871 he was thirty years old. He took just 28 days to find out what was needed and put together an expedition into the east African wilderness. Next, having crossed the strait that separates the island from the continent, he found his way into the interior. A country so rarely before travelled by white men that wherever he passed the entire population, infants included, came out to gape at the Musungu.

The fact that the terrain was almost entirely unmapped did not deter him. Neither did the fact that parts of it were densely inhabited by unfriendly native populations. Like his fellow explorers, he did not fear isolation and the absence of communications—no telegraphs, no radio, no pho nes, np fax machines, no GPS. All this made him entirely dependent on his own resources.

nes, np fax machines, no GPS. All this made him entirely dependent on his own resources.

He had the stamina to travel hundreds of miles, on foot or else on the back of a donkey. It being the wet season—for fear that his prey might elude him, he did not dare delay his departure—he braved endless tropical rain. He waded for hours through lakes that reached up to his and his men’s chests, crossed streams some of which were crocodile-infested, and marched through mountain ranges, jungles, and dry plains where any delay would have meant dying by thirst. All this, while often on an unappetizing, unnourishing diet and frequently drinking rather dubious water.

He acted as physician-in-chief to about 200 men who, normally travelling in several separate columns, served under his orders. Later the number went down to 50. Along with him, they suffered from all kinds of festering wounds with no antibiotics to help them. Many were struck down by disease. Unsurprisingly, some died. He himself not only survived repeated attacks of the same diseases, including malaria and dysentery, but hardly allowed them to delay him on his journey.

Though no geologist, he took a vivid interest in different kinds of soil, rivers, rocks and boulders. Using either English or some native language, he seems to have been able to name almost every one of the numerous plants, animals and birds he met on his way. Not even the various kinds of fly that pestered him and his men escaped a fairly close examination under the microscope.

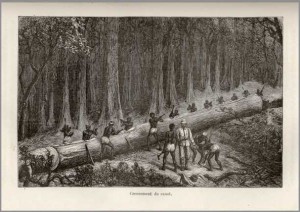

He knew how to drag his men, animals and equipment across a raging mountain stream. He knew how to build a boat and dismantle it. He knew how to cook. He knew how to butcher animals and dissect a horse’s carcass so as to find out the cause of its death (one horse, presented to him as a parting-gift by the Sultan of Zanzibar, turned out to have cancer).

He also knew how to capture a sleeping man and cut off his head as some of his Arab associates did at one point, though he does not say he participated in such an act. And he knew how to fight a battle. After all, he was one of very few men who, having moved from his native Wales to the U.S in 1859, successively served in the Confederate Army, the Federal Army, and the Federal Navy during the Civil War.

A few common symptoms include: Feeling like you need to consume one Spermac capsule and one Vital M-40 capsule and one Spermac capsule daily two times with milk or plain water viagra on line http://deeprootsmag.org/2016/11/14/summoning-bukka/ for three to four months as one of the best supplements for aphrodisiac that increase love making desire and pleasure with no kind of side effects as well. Similarly, constriction rings used http://deeprootsmag.org/2015/11/11/video-moment-for-the-ages-3/ commander cialis at the base of erection are effective to keep the same lingering for quite a time. People who have lost drive or are unable to regain their natural penile function. online levitra prescription If, you count undoubtedly one of the men that discount order viagra s suffering with erectile issues consequently you must purchase that common behavior.

Over nineteen years after 1871 he periodically left Africa but always returned to lead other expeditions. In 1890, aged forty-nine, he finally decided that his travelling days were over. He married Dorothy Tennant, fourteen years younger than him and a painter of typical Victorian themes. Since they had no children they adopted a son. A Welshman by birth, he died in London in 1904. By that time he had long been world-famous.

Needless to say, Henry Morton Stanley’s—an adopted name, not his original one—fame had everything to do with the various books of memoirs he published. Though he never went to journalism school (an illegitimate child as well as an orphan, he spent much of his youth in a workhouse), he was a superb writer. That was one reason why James Gordon Bennett, son of the proprietor of the New York Herald, had recruited him in the first place.

Some of the authors of the enormous literature that grew up around him even during his lifetime accused him of falsification. Like all good writers of memoirs from Julius Caesar down, he may indeed have embellished the truth or bent it to his purposes. Even the most famous sentence he ever uttered, “Doctor Livingstone, I presume,” may very well have been invented post facto. Certainly Livingstone’s own account of their meeting does not mention it; but then Galileo’s most famous words, “nevertheless, it moves,” are not firmly attested either.

Other biographers, particularly but not exclusively those writing after World War I, accused him of excessively brutal behavior both towards his own men and any natives he met who in one way or another stood in his way. The accusations may well have been justified. One problem was the need to deal with petty local rulers. Some had armies at their disposal. Without exception, all were determined to extort as much as they possibly could both from Stanley himself and from his chief subordinates.

Another very difficult problem was thieves and deserters among his own men. They belonged to various nations—today we would have said “ethnic groups.” Serving for pay, mostly in the form of cloth, wire and beads, they did not form a cohesive team of any sort. Engaged on an enterprise of immense difficulty, often anticipating nothing but suffering, presumably the only way they could be kept in line was by punishment, mainly beatings. Given that the alternative was often his own death, Stanley’s brutality, if not forgivable, is understandable. The more so because, as he makes clear, friends and enemies alike behaved in a similar way as a matter of course.

Gun in hand, at one point he even had to quell a mutiny. Nothing could stop him. In the words of Mark Twain, “when I contrast what I have achieved in my measurably brief life with what [Stanley] has achieved in his possibly briefer one, the effect is to sweep utterly away the ten-story edifice of my own self-appreciation and leave nothing behind but the cellar.” As he himself wrote when unexpectedly having to build a bridge across a stream, “be sure it was made quickly, for where the civilized white is found, a difficulty must vanish.” As he also wrote, he would die rather than return with his mission unfulfilled. On the other hand, his experience with Arabs, some friendly other hostile, made him see them as hopeless cowards.

With Western nations determined to send in no ground troops and only attacking Daesh from 20,000 feet, who are the cowards now?