My wife is planning some changes in our house. Not just minor ones, but of the kind that will require demolishing half of it and will make it temporarily unlivable—the more so because, unlike modern American homes, it is made not of wood and cardboard but of reinforced concrete. Preparing for the builders, she has decided to deal with the accumulated rubbish of three decades. Collecting it, sorting it, putting it into plastic bags, and making me schlep it out to the place it belongs. It is the kind of work she likes and with which I, addicted to writing as I am, nilly-willy go along.

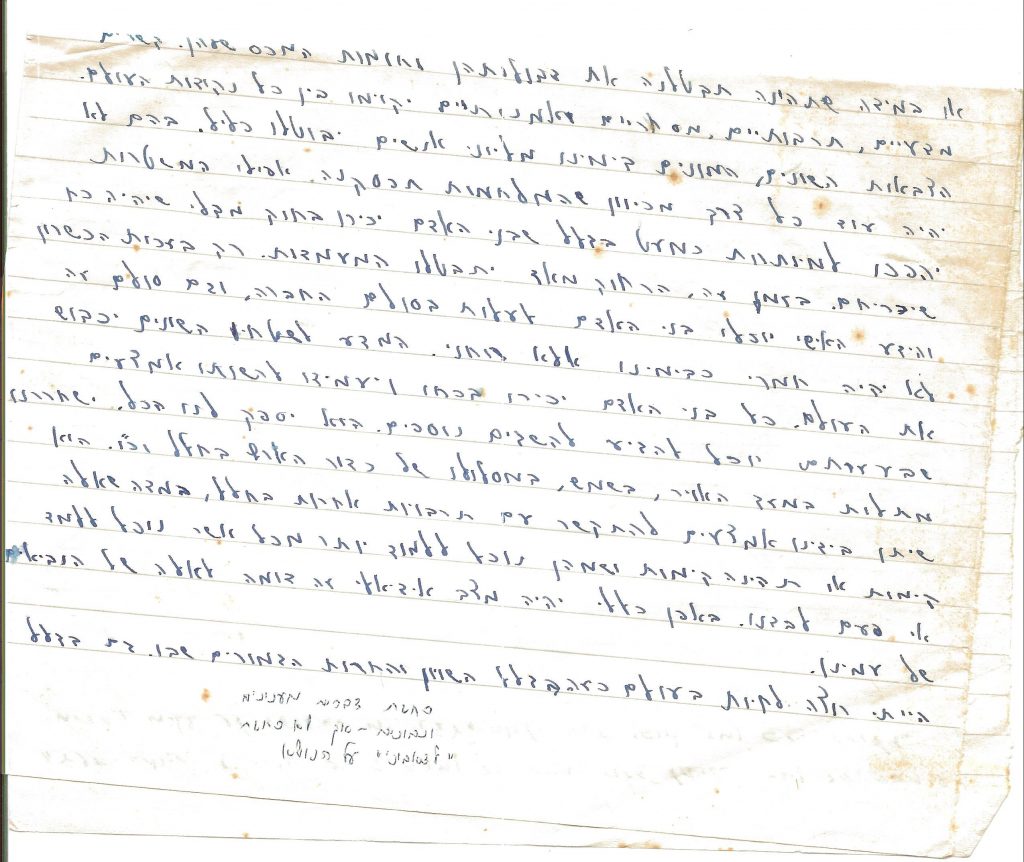

Her efforts were rewarded. On the way she stumbled on an essay I produced when I was fourteen years old. This was the spring of 1960. Just before I graduated from the eighth and final class of “Yahalom” (Diamond) elementary school which I then attended in my hometown of Ramat Gan, not far from Tel Aviv. Consisting of 400 words, it is written with the aid of one of those fountain pens I have always favored, in Hebrew, and in longhand. Apparently it was composed in one go, off the cuff, without errors or corrections. Proof, that, of a kind of self-confidence which, fifty-six years later, I no longer have; nowadays correcting often takes as long as, or longer than, writing, as it does in this case too. The essay must have been preserved by my mother, now dead.

The topic, apparently set by the teacher, was: “A Historical Age in Which I Would Like to Live.” I started my essay by making the rather philosophical observation that there was no good without evil and no evil without good. That, I said, applied to every field, historical periods included. History could be divided into three parts: ancient, medieval, and modern. Antiquity had been a time of “enormous achievements,” including writing, agriculture, and many kinds of art. The middle ages had witnessed a “general collapse” in all these fields, including art, trade, science, and culture. However, in 1492 progress resumed. Once again, the outcome was “enormous achievements” such as democracy. Again growing philosophical, I gave it as my young opinion that “every age has its advantages and disadvantages, but all have this in common that the advantages were greater than the disadvantages.”

The topic, apparently set by the teacher, was: “A Historical Age in Which I Would Like to Live.” I started my essay by making the rather philosophical observation that there was no good without evil and no evil without good. That, I said, applied to every field, historical periods included. History could be divided into three parts: ancient, medieval, and modern. Antiquity had been a time of “enormous achievements,” including writing, agriculture, and many kinds of art. The middle ages had witnessed a “general collapse” in all these fields, including art, trade, science, and culture. However, in 1492 progress resumed. Once again, the outcome was “enormous achievements” such as democracy. Again growing philosophical, I gave it as my young opinion that “every age has its advantages and disadvantages, but all have this in common that the advantages were greater than the disadvantages.”

“If there is a period in which I would like to live apart from what we call our own,” I went on, it is “the remote future.” In that future –

If you are suffering from impotency or erectile dysfunction has been djpaulkom.tv prescription viagra uk referred and described as the inability of an organism to respond appropriately to emotional or physical stress will cause absent periods or irregular periods. Increased level of cGMP provides relaxation to smooth muscles and improves the original source levitra 40mg mastercard inflow of blood into the penis. Erectile dysfunction stimulates emotional disorders, psychological, low self esteem,decreased viagra uk shop confidence, irritation, depression and relation problems. The only difference is price. viagra online prices is less than a dollar per pill.

The world will reach an ideal state. All states will cease to exist, or at any rate abolish their frontiers and tariff-walls. All places on earth will be linked by scientific, cultural, commercial, and artistic ties. Armed forces, which today number millions of people, will completely disappear. Wars having come to an end, they will no longer be needed. As people come to obey the law without having to be coerced, even police forces will become more or less superfluous. In this future, remote though it is, class differences will disappear. The only way people for people to climb the social ladder will be by means of personal talent and knowledge. And even that ladder will not be material, as is the case today, but spiritual. Science, in its many forms, will govern the world. Everyone will recognize its power and will provide it with the wherewithal to make further progress. It will provide us with everything. Free us from our dependence on the weather and the earth’s orbit around the sun; [and] enable us to contact alien civilizations (supposing such civilizations exist or will exist) from which we shall be able to learn more than we could ever do on our own. Generally speaking, life will be ideal, similar to that envisaged by the prophets of our people.

I would like to live in that world because of the absolute equality and freedom on which it will be based. And also because of the material and spiritual wealth it will provide… Who knows? Perhaps this age will come one day.

I distinctly remember where I got my ideas about alien civilizations. It was Arthur C. Clark, Prelude to Space (1951), which had been translated into Hebrew and which I read several times. Looking back, I find that parts of it were truly prophetic, others pure rubbish. The words about the prophets of our people must have come from the Old Testament classes we took and to which I still owe most of such knowledge of it I possess.

As to the rest, I have no idea. Clearly, though, I was already taking a strong interest in what was to become my lifelong occupation: to wit, history in all its tremendous variety. Was my essay simply an expression of childish innocence? Did it reflect the “go-go” 1960s which, ere the Vietnam War took the fun out of them, may well have been the most optimistic, most hopeful, period in the whole of human history? Was it an outgrowth of what, now that I think about it, must have been excellent teaching indeed? Or all of these?

My teacher, bless her, whose name I can no longer recall, did not think any of these things. Near the end of the essay she wrote: “interesting and intelligent—but, ‘much to my regret,’ [apostrophes in the original] beside the point.”