Back in the spring of 1994, the CIA was in a bad way. Not because of a threat to national security; after all, the Soviet Union had just fallen apart, most of China’s rise was still in the future, and the US continued to enjoy the protection not of one ocean but of two. Rather, it was the lack of “peer competitors” to spy upon and warn against. Saddam Hussein and Iraq having been defeated, probably never in human history had a single colossus appeared to be so dominant and so powerful! And what, pray, do you do when you do not know what to do? Short answer: you bring in a consultant. Or, better still, entire teams of consultants to consult with.

That is where I got involved. Three years earlier I had published The Transformation of War, a book President Clinton was said to have read or at any rate ordered. Now someone at the CIA contacted me and asked me to give a short talk about “the most important threat facing the US” as well as write a paper on the same topic. Arriving at Langley at the appointed day and hour, I was ushered into a meeting hall where the analysts were waiting. Most appeared to be in their mid- to late thirties, meaning they were no longer at the entry level but had much of their careers still in front of them. Following my pearls of wisdom, which took about 45 minutes to deliver, we launched into the Q&A. En fin, the usual staid format many of us are familiar with and take more or less for granted.

What they did not take for granted, and saved the meeting from being staid, was one single word that kept recurring: Mexico. Not because it was in any sense a peer competitor—it was not and still isn’t. Not because it had nuclear weapons—it did not and still doesn’t. Not because it had the armed forces to invade the US—it did not and still doesn’t. And not because it was strong, united, highly developed, and determined to confront the US. But precisely because it was not strong, and not united, and not highly developed; let alone determined to confront the US.

When the Q&A started it was my turn to be surprised. Of the fifty or so persons in the room not a single one seemed to agree with me; then and later quite a few told me I had been spouting… well, you know what. After all, the US was much larger and stronger than Mexico. In terms of GDP (both total and per person), industrial capacity, armed forces, capacity for innovation, human capital (basically, literacy and the number of years spent at school) and, last not least, the “soft power” which at that time was being touted by Professor Joseph Nye at Harvard there simply was no comparison. True, Mexico with its 88 million people and 761,610 square miles of territory was not exactly a pigmy. Further south, some Latin American politicians even let loose an occasional reference to it as “the giant of the north.” But the most dangerous problem facing the US? Come on.

Twenty-two years later, in 2016, Nye’s fellow Harvard professor Samuel Huntington published Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity. Like Nye, Huntington focused less on material factors—so and so much of this, so and so much of that—as on cultural values. English rather than Spanish or some other language(s). Individualism versus a more family-oriented society. Respect for the law, normally seen not as an instrument for oppression but as a necessary framework for imposing justice and enabling society to function. The kind of society that in some ways helped turn most people into quasi-Protestants even without them knowing it. All these were being undermined by hordes of immigrants, either Mexicans or, increasingly, other Latin Americans originating in countries further to the south. Many immigrants did not even try to assimilate. Instead, entering ghettoes that were at least partly self-imposed, they proudly pronounced their original identity and their determination to stick to it even while defying the surrounding “native” population.

Nor does Mexico itself have much to be proud of. In 2021 the human development index (HDI), which is the one used by the United Nations to measure the progress of a country, stood at 0.758 points, leaving it in 86th place in the published table of 191 countries. Contributing to this sad state of affairs is a fairly low per capita GDP of $ 11,500 per year, just one sixth of the US figure. Next come widespread violence (the seven cities with the world’s highest per capita homicide rates are all located in Mexico); a large but inefficient government apparatus; wealthy and powerful drug cartels that are often both integrated into the government machinery (and the military, and the police) and capable of standing up to them. To these, add corruption; limited freedom of the press (in 2024 Mexico occupied place number 121 out of 180 countries); an exploding population that, between 1994 and 2024, went up 48 percent, in many ways making it necessary to run like hell just to stay in place; and a geographical position that made it a conduit for countless additional people from all over Central and South America.

Following the events of 1945-1960, when most of the former colonial countries in Asia and Africa achieved their independence, there was a widespread expectation that “they” (the countries in question) could and would become more like “us” (the “developed” west). So, for example, President Johnson’s National Security Adviser Walt Rostow (served, 1966-69) in his influential 1959 volume, The Stages of Economic Growth, which laid out a program for doing exactly that. In fact, though, the opposite is happening. A vast and apparently unstoppable influx of people is moving from south to north. With their number estimated at 2,4 million in 2023 alone, they either undermine or overwhelm the ability of American institutions, from the police to schools to hospitals to welfare systems, to cope. Instead of “they” becoming like “us,” “they” are well on the way of turning “us” into “them.”

Mexico’s recent elections, which for the first time put a woman at the helm, has been keenly followed both in- and out of the country. And rightly so; who knows, maybe she will start moving her people in the right direction. Meanwhile, though, America’s southwestern states in particular are begging for help so they can cope with exactly the situation I and others predicted thirty years ago.

And what has the Federal Government been doing? For decades on end, the answer was nothing.

Shortly after Mr. Biden took office, I posted a short piece—No. 367, to be precise—on “What I Want of Joe Biden.” Now that the Congressional elections are just weeks away, I want to try and see the extent to which my

Shortly after Mr. Biden took office, I posted a short piece—No. 367, to be precise—on “What I Want of Joe Biden.” Now that the Congressional elections are just weeks away, I want to try and see the extent to which my

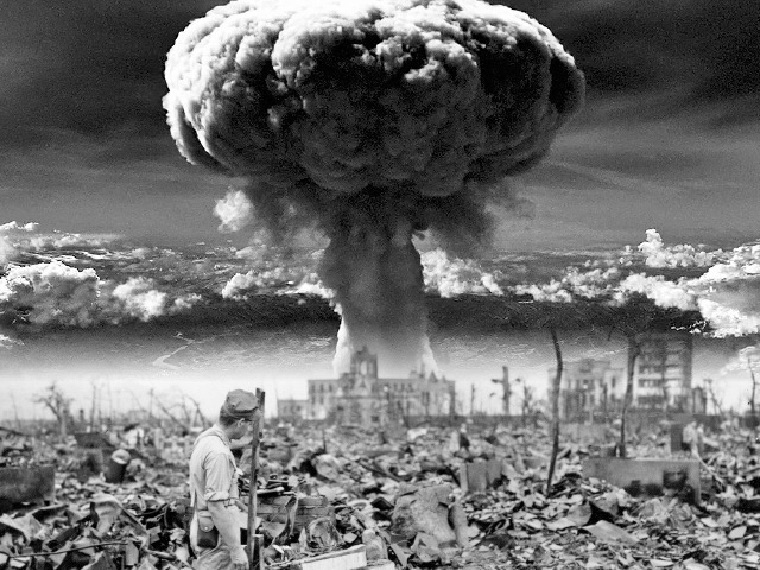

Ever since 1945 peace among the great powers, such as it is, has been guarded above all by nuclear weapons and their delivery vehicles. Weapons so powerful, and so hard to stop on their way to target, that, should they ever be used in any numbers, they can literally put an end to mankind. The balance of terror, as Winston Churchill and others called it.

Ever since 1945 peace among the great powers, such as it is, has been guarded above all by nuclear weapons and their delivery vehicles. Weapons so powerful, and so hard to stop on their way to target, that, should they ever be used in any numbers, they can literally put an end to mankind. The balance of terror, as Winston Churchill and others called it.