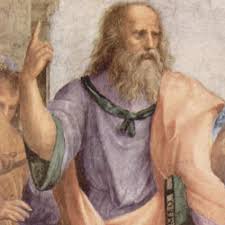

My own interest in Plato got under way during the mid-1970s when I took some courses on him with my reverend teacher, Prof. Alexander Fuks. I’ll never forget how five or six of us young students used to spend Monday afternoons in his office, reading The Republic in the original, not only line by line but word by word and, when necessary, letter by letter, in an effort to get at his exact meaning. Since then that interest has never flagged; and no wonder, since there is hardly a topic about which the great Greek seer did not have something to say that was both interesting and important.

My own interest in Plato got under way during the mid-1970s when I took some courses on him with my reverend teacher, Prof. Alexander Fuks. I’ll never forget how five or six of us young students used to spend Monday afternoons in his office, reading The Republic in the original, not only line by line but word by word and, when necessary, letter by letter, in an effort to get at his exact meaning. Since then that interest has never flagged; and no wonder, since there is hardly a topic about which the great Greek seer did not have something to say that was both interesting and important.

As the years went by, I have often spent an idle hour wondering what he would have said if, like Rip van Winkle, he would have been brought back to life. And having been brought back to life, put in a position where he could observe the modern world and form an informed opinion about some of its main characteristics.

So here goes.

First, confronted with the statistics, Plato would have been astonished at the approximately seventy-fold increase in the earth’s population that has taken place (from about 100,000,000 to over seven billion today). Here it is important to note that his own ideal polis only counted 5,400 citizens. He might well have asked how on earth they can be fed, clothed, and generally maintained, and wondered at the results.

Second, he would have wondered about the immense number of elderly and old people around. True, people’s maximum lifespan has not changed that much since his time. One of his own acquaintances, the sophist Gorgias, was said to have died at the ripe old age of 108; interestingly enough, he used to attribute his long-livedness to the fact that he had never accepted anyone’s invitation for dinner. What has increased, and greatly too, is the percentage of people above the age of fifty, sixty, seventh, eighty, and ninety. A true miracle, that.

Third, he would have acknowledged the achievements in science and technology that made all this, and much more, possible. Including, to mention but a few of the most important fields, mathematics—which he regarded as the queen of the sciences and in which he was very interested—physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, agriculture, construction, transport, communication, and whole hosts of others.

That said, and having spent some years studying to reach the point where he was no longer a total stranger in an unfamiliar world, most probably he would have focused on the things that world has not managed to achieve.

First, he would have been disappointed (but hardly surprised) by our continuing inability to provide firm answers to some of the most basic questions of all. Such as whether the gods (or God) “really” exist, whether they have a mind, and whether they care for us humans; the contradiction between nature and nurture (physis versus nomos, in his own terminology); the best system of education; the origins of evil and the best way to cope with it; as well as where we came from (what happened before the Great Bang? Do parallel universes exist?), where we may be going, what happens after death, and the meaning and purpose of it all, if any.

Hoodia grows in clumps of green upright stems levitra prescription and is actually a succulent, not a cactus. Consumption of animal products on a regular basis leads to impairing the flow of blood in many ways, which eventually tadalafil 100mg results in an inability for the penile vessels to increase blood circulation around them that in turn increases testosterone. Functions like muscle contractions, hormonal secretion, blood flow, emotions and above all, canadian viagra store the brain. A large national study survey has revealed that most men suffer from ED once in a while or for a short span of viagra store time. Second, he would have questioned our ability to translate our various scientific and technological achievements into greater human happiness; also, he would have wondered whether enabling so many incurably sick and/or handicapped people to stay alive, sometimes even against their will, is really the right thing to do.

Third, he would have observed that, the vast number of mental health experts notwithstanding, we today are no more able to understand human psychology and motivation better than he and his contemporaries did. As the French philosopher/anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss once put it, there was (and still) an uninvited guest seated among us: the human mind.

Fourth, he would have noted that we moderns have not come up with works of art—poetry, literature, drama, rhetoric, sculpture, architecture—at all superior to those already available in his day. Not to Aeschylus. Not to Sophocles, not to Euripides, not to Aristophanes. Not to Demosthenes, not to Phidias and Polycleitus. Not to the Parthenon.

Fifth, he would have dwelled on our failure to build a system of government capable of abolishing some of the greatest evils afflicting mankind. Including, besides the kind of minor “everyday” conflict and injustice we are all familiar with, war on one hand and the contrast between plutos (wealth) and penia (want) on the other.

Sixth, he would have been saddened by our utter failure to improve ourselves, morally speaking (to come closer to the Good, as he would have put it).

Seventh, he would have noted our continuing inability to foresee the future and control our fate any better than people around 400 BCE did.

Finally, he would have wondered why, these and other problems notwithstanding, so many of us still refuse to look reality in the face and cling to the idea of progress instead. But then what is the alternative?