A question about the Ukrainian War that many Westerners have been asking—and that must have been haunting those hard-faced men in the Kremlin ever since they started their offensive on 24 February—is what they, the hard-faced men, have been doing wrong. Also, what the Ukrainians, waging war under the remarkable leadership of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, have been doing right. Focusing, as far as possible, on the military sphere as opposed to the political and economic ones, and recognizing that the time for a comprehensive analysis of the war has not yet arrived, the following represent some preliminary answers. Such as may also be useful to other militaries which are watching events and trying to draw lessons from them.

What the Russians have been doing wrong

First, the Russians have greatly underestimated the Ukrainians’ determination and willingness to fight. How this could have happened is anything but clear. Perhaps it was born out of previous Russian successes in Georgia (2008), the Crimea (2014) and Nagorno-Karabakh (2020). Or else they may have fallen victim to their own propaganda about Russians and Ukrainians having been one people for so long that the latter would not fight the former in earnest.

Second, and possibly because of the above, the Russians did not mobilize sufficient forces. The above apart, they may also have feared domestic problems in case they went too far in this respect. However that may be, contrary to the prevailing impression in terms of the number of available maneuver battalions the Ukrainians were not at all inferior to the Russians. Fighting on interior lines as they did, in places they may even have been superior. Conversely, sheer lack of numbers seems to have played a major role in the Russian failure to capture, first Kiev and then Kharkov. To make things worse, most of the Russian ground forces consist of short service, insufficiently motivated and trained, conscripts.

Third, it would seem that the Russian General Staff was unable to decide what the most important objective (Schwerpunkt) of their offensive was going to be. As a result they tried to advance in no fewer than four different directions at once—from the north on Kiev, from the east on the Donbas, and from the Crimea both east and west. Later they even added another thrust, i.e the one on Kharkov. Had the Russians enjoyed a considerable numerical superiority, such a strategy might have been feasible; as I just said, however, of such a superiority there could be no question. As a result, out of the five offensives three, i.e the one against Kiev, the one against Kharkov, and the one reaching west towards Odessa had to be abandoned. Only the one against the Donbas really made progress—but only very slowly, and only at high cost.

Fourth, the Russians chose the wrong season for launching their offensive: first snow, making movement difficult, then thaw, then mud. There is no question that, militarily speaking, it would have been better to wait another few weeks; why Putin did not do so is unknown.

Fifth, given the scale of preparations and the time it took to make them there was no question of the Russians enjoying the benefit of surprise. Conversely, the Ukrainians had all the time in the world to get ready.

Sixth, as the enormous traffic jam on the roads leading south from Russia to Kiev showed, logistic planning was totally inadequate. The outcome seems to have been on- and off shortages of fuel and ammunition (which, in any modern war, form the bulk of the troops’ requirements) and even food.

Seventh, contrary to expectations the Russians did not make extensive use of their superior air force. First, the attempt to end the war by means of a coup de main directed against a major Ukrainian airport on the outskirts of Kiev ended in failure. Subsequent air operations, all kinds of missiles included, appear to be scattered and ineffective. True, Ukraine’s armament industry has been destroyed. But Russian airpower does not seem to have availed them much against mobile Ukrainian forces in the field.

Finally, a “cyberwar Pearl Harbor,” as it has sometimes been called, did not materialize. To be sure, there has been a great many attacks some of which knocked out websites, disrupted communications, and the like. However, large scale anarchy, let alone paralysis, did not result. Whether that is because of insufficient preparation or because the other side was ready is not clear.

What the Ukrainians have been doing right

First, though both sides have relied on semi-regular militias (including, in the Russian case, mercenaries) to do part of their fighting, this form of military organization has played a greater part on the Ukrainian side than on the Russian one. Not only does this fact help explain the way the latter’s numerical superiority has been largely obviated, but it provided the Ukrainians with a certain kind of flexibility. Enjoying a large degree of autonomy as they do, the militias could not be neutralized simply by striking at central Ukrainian headquarters.

Second, whereas the invaders must generate their own intelligence, the Ukrainians can receive theirs from almost every man, woman and child in the country. The fact that, though the weapons used on both sides are often almost identical, the Russians have chosen to mark theirs with large letters Z helps.

Third, the Ukrainians have been making unexpectedly good use of modern weapons, especially the drones needed for in-depth reconnaissance behind the front. And including also anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles generously provided by the West.

Fourth, on the whole they have not tried to stop the Russians by waging large sale warfare, army against army, in the open. Instead they defended the cities where winning requires the kind of numerical superiority the Russians do not have.

Finally, while the destruction inflicted on many of Ukraine’s cities has been terrible, wherever possible the Ukrainian military did not fight to the last man and the last bullet. Instead, it regularly left room for their forces’ more or less orderly retreat. Mariupol, where they allowed themselves to be put under siege, is the exception, not the rule. One which, in the future, they would be wise to repeat.

In summary

In summary the Russians, by underestimating the opponent and giving up on surprise, have committed the worst of all military sins. By contrast, the Ukrainians have exploited the Russian mistakes right up to the hilt.

However, two points are worth making. First, the available information is slanted, unreliable and, above all, extremely fragmentary. Nowhere is that more the case than in the number of dead and injured on both sides; as the saying goes, in any war the first casualty is always the truth. Second, this war is by no means over yet. The signs are that the iron dice will keep rolling for a long time, and how they will ultimately land is anyone’s guess.

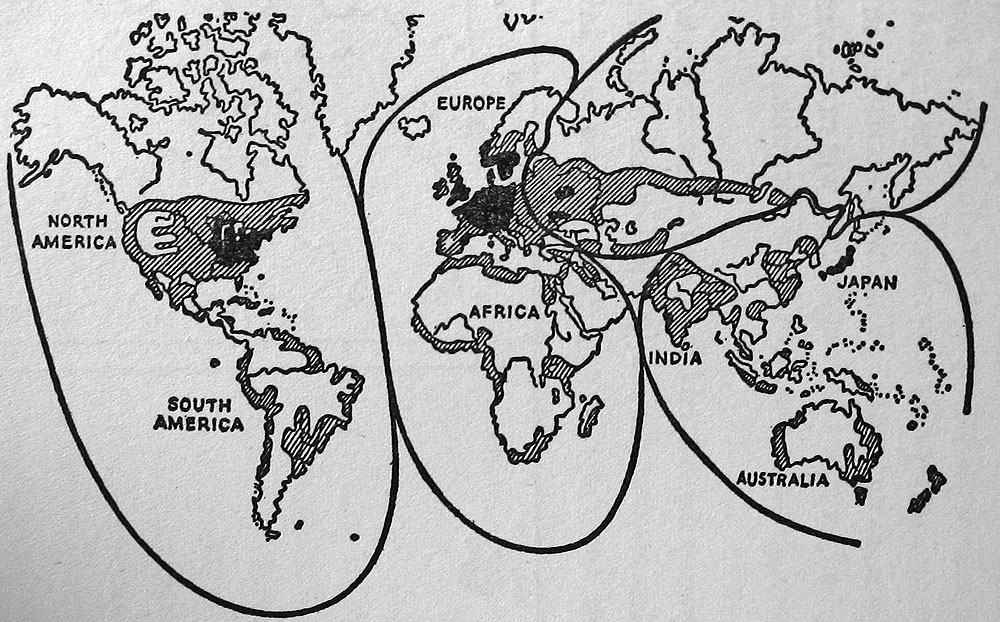

Two basic ideas dominate this book. The first is that the post-Cold War era has definitely ended and that we have now entered the era of “the global enduring disorder;” a claim fully confirmed by recent events in Ukraine. The second is that Libya, which most people see as a failed state made up of oceans of high-quality oil, vast stretches of pitiless desert, and bands of fanatical Toyota-truck riding gangsters that keep on fighting each other both acts as a microcosm of that disorder and is playing an important role in extending it

Two basic ideas dominate this book. The first is that the post-Cold War era has definitely ended and that we have now entered the era of “the global enduring disorder;” a claim fully confirmed by recent events in Ukraine. The second is that Libya, which most people see as a failed state made up of oceans of high-quality oil, vast stretches of pitiless desert, and bands of fanatical Toyota-truck riding gangsters that keep on fighting each other both acts as a microcosm of that disorder and is playing an important role in extending it