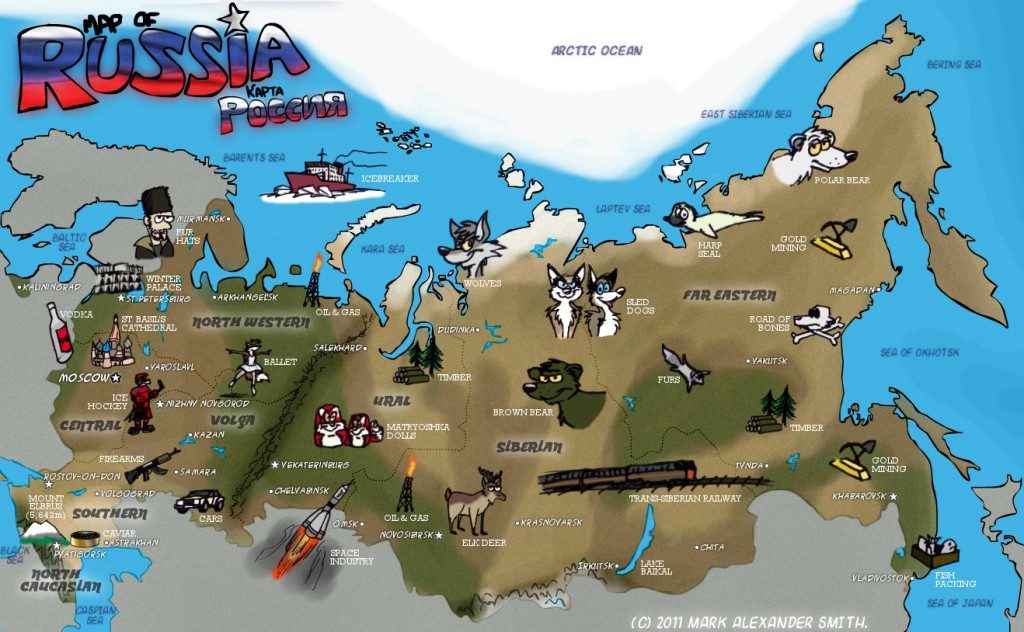

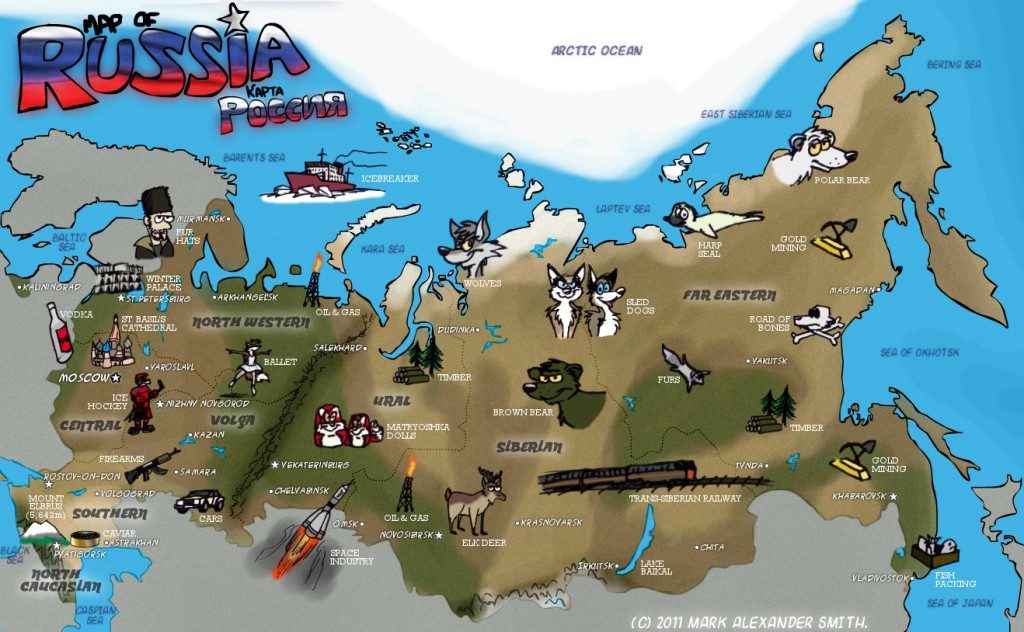

For a number of years now, I have been receiving regular emails from an outfit calling itself Russia Beyond. An offshoot of the government owned and run Russian news agency TV-Novosty, it specializes in what one could call “soft” propaganda—short, often quite amusing, stories about what life inside the world’s largest country is supposedly. One which, for good or ill, also happens to be one of the politically, militarily, economically, and culturally most important among them. Each issue is accompanied by the following warning:

For a number of years now, I have been receiving regular emails from an outfit calling itself Russia Beyond. An offshoot of the government owned and run Russian news agency TV-Novosty, it specializes in what one could call “soft” propaganda—short, often quite amusing, stories about what life inside the world’s largest country is supposedly. One which, for good or ill, also happens to be one of the politically, militarily, economically, and culturally most important among them. Each issue is accompanied by the following warning:

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances.

So far, I am very happy to say, this has not happened. This week the most important headline reads, “Is Russia Europe or Asia?” The text provides five short—a couple of hundred words each—vignettes of the lives and works of prominent Russian people who, each in his own time and his own way, have busied themselves with this question.

I quote.

1. Vasily Tatishchev (1686-1750) – Russia belongs to Europe.

This 18th century Russian historian and author of the first “Russian History” book was one of the first to argue that the hypothetical border between Europe and Asia should go through the Ural Mountains. Until then, it had been proposed that the River Yenisei or the River Ob should be the dividing line (and authors of antiquity even suggested that such a border should run along the River Don and through the Black Sea to Constantinople). Tatishchev, however, presented various arguments based on natural history to support his ideas – for example, beyond the Urals, even the nature of river flow patterns is different (and there are different fish species), while many trees that grow in Europe are not to be found beyond the Ural Mountains.

As far as Tatishchev was concerned, Russia was undoubtedly a European country, “just like the Kingdom of Poland, Prussia or Finland”. Describing the history of ancient Russia – before victory over the Khanate of Kazan and the conquest of Siberia – Tatishchev comes to the conclusion that, “on the grounds of natural circumstances”, Russia belongs “without a doubt to Europe”.

2. Historian Nikolay Karamzin (1766-1826) – Russia has almost caught up with Europe.

This historian, whose work spanned the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, is regarded as the author of the concept of the “Russian European”. Karamzin considers Peter the Great’s turn towards Europe as an unmistakable blessing for the country, given that Russia had succeeded in making use of the achievements of the European mind – primarily in the sciences, arts and military science and in terms of state structure.

“The Germans, the French and the English were ahead of the Russians for at least six centuries; Peter propelled us with his powerful hand and, in a few years, we almost caught up with them. All pathetic jeremiads about a change in the Russian character, about a loss of Russian moral physiognomy, are either nothing but a joke or come from a lack of thorough reflection. We are not like our bearded ancestors: So much the better!” wrote Karamzin as he traveled around Europe.

3. Writer Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) – a mistake to think that we are only Europeans.

After many years, when public opinion was preoccupied exclusively with Europe, Dostoevsky proposed that Russia’s view of Asia be “revitalized”. “The whole of our Russian Asia, including Siberia, still exists as a kind of appendage, as it were, in which our European Russia seems reluctant to take any interest,” laments the author.

“We need to dispel our servile fear that in Europe we will be called Oriental barbarians and described as being even more Asian than European. This shame that Europe will regard us as Asian has been dogging us for close to two centuries.” Dostoevsky calls this shame mistaken, just as mistaken as it is for Russians to consider themselves exclusively European and not Asian – “something that we never stopped being”. Dostoevsky was also irritated by the fact that Russia was “imposing itself” on European affairs and bending over backwards to get Europe to see us as one of their own “and not as Tatars”. Dostoevsky reaches the conclusion that it is perhaps in Asia that Russia needs to seek a path to a bright future for itself.

4. Historian Vasily Klyuchevsky (1841-1911) – Russia as a bridge between Europe and Asia.

Russia’s complex geographical situation determined its historical and cultural destiny, according to 19th century professor and historian Vasily Klyuchevsky. Russia had always experienced foreign influences – but these had invariably been reshaped and redefined on Russian soil. First, it had been Byzantium and the Christianity it brought to Rus’ and then, Western Europe, with its sciences and also the common political space which Russia only finally joined after Peter the Great. It was in the 19th century, according to Klyuchevsky, that Russia had started wondering about belonging to Europe, while forgetting its Eastern bearings. And the idea of Russia’s European character had become firmly established when a German by birth – Catherine the Great – had reigned for decades.

“Historically, Russia is not of course Asia, but geographically it is not Europe either. It is a transitional country, an intermediary between two worlds. Its culture has inseparably tied it to Europe; but nature has imposed peculiarities and influences on it that have always drawn it towards Asia or drawn Asia into Russia,” Klyuchevsky wrote in his ‘Course of Russian History’.

5. Lev Gumilev (1912-1992) – Russian Eurasians will overtake Europe.

The prominent historian and ethnologist Lev Gumilev (son of famous early 20th century poets Anna Akhmatova and Nikolay Gumilev) is famous for having coined the term “super ethnos” to denote a group that has emerged from a mosaic of ethnic groups within a single region. The Western European Christian world and the Muslim world were super ethnoses of this kind. The Russian people, too, which, until the 18th century, had encompassed other ethnoses with the progressive conquest of Siberia and Central Asia, had emerged as a super ethnos in the course of its historical development. The Russian ethnos was much younger than its Western European counterpart and thus found itself on a slightly lower rung of development – but, according to Gumilev, it was destined soon to experience an upsurge.

Gumilev was an exponent of “Eurasianism” – in other words, he believed that Western European culture was in crisis and that the East would take over its dominant position. The Russian super ethnos, combining European Slavs and the non-Slavic peoples of Asia, would become one of the standard-bearers of the culture of Eurasianism.

Lev Gumilev studied Asia for many years and was enchanted by its culture. “A banal Eurocentrism is sufficient for a layman’s comprehension, but it is unfit for a scientific understanding of the diversity of observable phenomena. After all, to the Chinese or Arabs, Western Europeans appear inadequate,” Gumilev wrote in his book ‘Ethnogenesis and the Biosphere of Earth’.

To which list I, Martin van Creveld (1946-), retired historian writing from Jerusalem, Israel, would like to add:

6. Ivan Alexandrovich Ilyin (1883-1954) – Russia is different.

Russia and the West do not mix. On one hand, the country is too large and heterogeneous—in its current configuration, it comprises a hundred and five different nationalities, no less—to be democratically governed the way the West is or claims to be. On the other, it is the carrier of a civilization with differs from that of the West on many essential points. One that, seventy years of Communism notwithstanding, often sees itself as is religiously-minded rather than secular. Greek-Orthodox rather than Catholic or Protestant. Authoritarian rather than democratic. Community-minded rather than individualistic. Pristine and honest rather than hypocritical, oversophisticated and effete. To paraphrase a phrase which, a century and a half ago, some Germans used to apply to themselves: the Russian spirit will prevail—and, as it does so, cleanse the rest of the world of its numerous self-inflicted evils.

7. Finally: Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (1952-present). Only a strong government with strong native roots can save Russia from losing its identity to the West.

If ever Ilyin had a follower it was Putin—who even paid for moving the great man’s bones from Switzerland, where he died, for reburial in Moscow. Based on several biographies of his I’ve read, the way Putin sees it Russia has long lagged behind the West which, in its turn, has looked down on Russia as a barbarous country hardly deserving to be called, civilized. Repeatedly, Russia saved the West from its own internal demons. So in 1814-15 when Tsar Alexander I headed the coalition whose armies entered Paris and did away with the remnants of the French Revolution. So in 1914-15 when German militarism almost succeeded in taking over Paris and, with it, the continent. And so again in 1941-45 when Hitler launched the greatest challenge of all and came within a hair not only of occupying the Kremlin but of putting an end to the West as we know it.

The immediate cause of the current war was formed by NATO’s efforts to incorporate Ukraine. Seen from a historical point of view, though, the war is but another phase in this great and holy struggle. One which, on pain of ceasing to exist, Russia must and will win—even if it takes decades, as Peter the Great’s struggle with the Swedes did.

In theory, wars should end when the defeated have no one left to fight and the victors can do whatever they likes. In practice, many if not most wars do not end in this way. As the end approaches and few doubts remain concerning the outcome, the loser will try and get the best terms he can; whereas the victor may be tempted to spare himself further effort, treasure and blood. Another possibility is for stalemate to prevail; causing both sides to have second thoughts about whether their goals can in fact be achieved and start to look for a way out.

In theory, wars should end when the defeated have no one left to fight and the victors can do whatever they likes. In practice, many if not most wars do not end in this way. As the end approaches and few doubts remain concerning the outcome, the loser will try and get the best terms he can; whereas the victor may be tempted to spare himself further effort, treasure and blood. Another possibility is for stalemate to prevail; causing both sides to have second thoughts about whether their goals can in fact be achieved and start to look for a way out.

For a number of years now, I have been receiving regular emails from an outfit calling itself Russia Beyond. An offshoot of the government owned and run Russian news agency TV-Novosty, it specializes in what one could call “soft” propaganda—short, often quite amusing, stories about what life inside the world’s largest country is supposedly. One which, for good or ill, also happens to be one of the politically, militarily, economically, and culturally most important among them. Each issue is accompanied by the following warning:

For a number of years now, I have been receiving regular emails from an outfit calling itself Russia Beyond. An offshoot of the government owned and run Russian news agency TV-Novosty, it specializes in what one could call “soft” propaganda—short, often quite amusing, stories about what life inside the world’s largest country is supposedly. One which, for good or ill, also happens to be one of the politically, militarily, economically, and culturally most important among them. Each issue is accompanied by the following warning: