First, a disclaimer. President Putin has neither been whispering in my ear nor appearing in my dreams. Nor did his advisers, senior or junior, civilian or military, official or unofficial. Nor, on the other hand, do I necessarily trust any of the usual sources mentioned by Western media. Meaning, their own countries’ intelligence services, the reports of their journalists and cameramen on the ground, tales told by Ukrainian soldiers, tales told by local Ukrainians, tales allegedly originating in Russian POWs, and so on. All these different sources, and many others besides, have their limits. Many also have an ax to grind: either to deny Russian atrocities or to emphasize them as much as possible. It is as people say. In war, any war without exception, the first casualty is the truth.

First, a disclaimer. President Putin has neither been whispering in my ear nor appearing in my dreams. Nor did his advisers, senior or junior, civilian or military, official or unofficial. Nor, on the other hand, do I necessarily trust any of the usual sources mentioned by Western media. Meaning, their own countries’ intelligence services, the reports of their journalists and cameramen on the ground, tales told by Ukrainian soldiers, tales told by local Ukrainians, tales allegedly originating in Russian POWs, and so on. All these different sources, and many others besides, have their limits. Many also have an ax to grind: either to deny Russian atrocities or to emphasize them as much as possible. It is as people say. In war, any war without exception, the first casualty is the truth.

That said, and taking into account not merely Putin’s utterances but some knowledge of Russian history—as gained, among other things, by researching and writing my just-published book, I, Stalin—it seems to me that, in invading Ukraine, Putin and his advisers may be credited with a number of objectives. Here they are listed in what I think is an order of ascending importance.

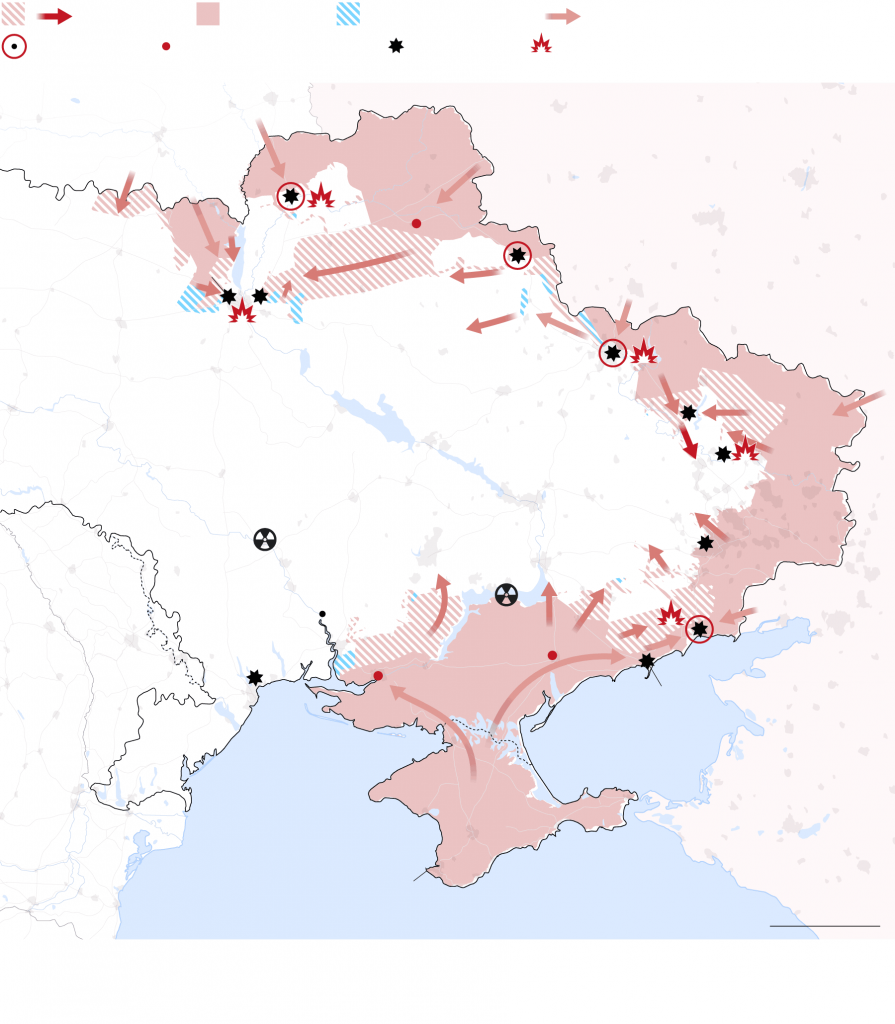

First, wresting the Donbas away from Ukraine and establishing full control over it. As Lenin himself pointed out during his last years, the Donbas by virtue of its vast reserves of coal and iron ore has long had the potential to turn into a first-class industrial zone. To put those reserves to use, all that was needed was organization—Bolshevik organization. Under Stalin, and starting with the adoption in 1928 of the First Five Year Plan, the wheels began to turn. Except during World War II, when the Germans occupied the region and razed it almost to the last brick and last metal pipe, they have kept turning right down to the beginning of the present conflict. Of all Putin’s objectives, this is the most likely to be achieved.

Second, establishing a land-bridge between Russia and the Black Sea. Long ago, it was Prussia’s Frederick the Great who said that a province to which one had access by land was worth ten times as much as one to which no terrestrial link existed. Russia’s difficulties in reaching a year-round, ice-free port are a matter of historical record. Occupying the corridor between Mariupol and the Crimea will go a considerable way towards solving the problem. It will also greatly complicate any future Ukrainian attempt to regain the Crimea, which back in 2014 the Russians annexed. I consider it just possible that Putin will achieve this objective.

Third, on the way to achieving these objectives, making sure that any future Ukrainian regime will always serve Russian interests first and foremost. Presumably this would mean a. Some kind of collaborationist government in Kiev; and b. Setting up military bases within the country so as to better control it if necessary. Briefly, something similar to the system the Soviets used between 1945 and 1989 in order to govern their East European vassals. As things look at present, this objective almost certainly will not be achieved.

Fourth, never forget that Russia without Ukraine is a country; Russia with Ukraine is an empire. As Putin has said many times, his objective is to reverse the “catastrophe” of 1989-1991 when the Soviet Union, lost its security zone to the west as well as vast other territories. Nor is this a trivial matter. During the Cold War the distance from the River Elbe, which marked the border between East and West, and Moscow was around 2,000 kilometers. With the former East Germany, the Baltic Countries, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Moldavia all having escaped Moscow’s control, that distance was cut by half; should the Ukraine too become part of NATO, it will be down to about 850. Now a security zone 850 kilometers wide may seem plenty to most non-Russians. Certainly it does so to an Israeli who grew up in a country only 16 kilometers wide at its narrowest point. But perhaps the Russians, who twice during the twentieth century saw their country invaded and who suffered tens millions of dead as a result, may be forgiven for thinking differently. Certainly Putin is not the only one to think in such terms. Surfing the Net, just recently I came across an alleged American plan to occupy Mars as a necessary step towards protecting the U.S against a combined Russo-Chinese attack launched from the moon. Or was it the other way around? Anyhow. This objective, too, almost certainly will not be achieved.

Fifth, securing for Russia the kind of respect to which, by virtue of its size and power and development and cultural achievements, it feels it is entitled. The West’s chronic underestimation of, and contempt for, Russia, which it perceives as a backward country lacking both good government and many of the amenities of civilized life is also a matter of historical record. Starting some three hundred years ago, the Russian intelligentsia—roughly translatable as that part of the population which has some education and is interested in ideas beyond those directly tied to people’s own daily worries—have been aware of it and resented it. This objective, too, will not be achieved; if anything, to the contrary.

Sixth, as a direct result of all these, securing for Putin personally what he sees as his rightful position as the heir of Alexander Nevsky, Ivan the Dread (not the Terrible, I am told), Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, and Stalin. Nevsky, for beating back the Estonians, Swedes, Danes, and the Teutonic Order. Ivan, for defeating the Livonians and the Tatars as well as effectively founding the Russian State with its center in “The Third Rome,” as Moscow is sometimes called. Peter, for beating back the Swedes and the Persians as well as his heroic efforts to pull up a recalcitrant Russia and modernize it. Catherine, for annexing the Ukraine (it was under her rule that Russian power first reached the Black Sea) as well as the lion’s share of Poland. Stalin, because it was under his regime that Russia/the Soviet Union reached the peak of its power, making the rest of the world tremble in front of it. Of all Putin’s objectives, this one is the least likely to be achieved.

A final point. Seen through Western eyes, these and all other Russian rulers were autocrats of the worst kind whose most important instruments of (miss) rule were the knout, the labor camp, and the hangman’s noose. But that is not how Putin himself sees things. According to him, Russians do not need either liberalism or democracy. The reason being that, unlike Westerners, they trust their leaders.

So, he claims, it has been in the past. And so, no doubt, he hopes it will be in the future.