The place: the area around Kursk, a Russian (formerly Soviet) city about 520 kilometers south of east of Moscow and 420 kilometers east of Ukraine’s capital Kiev. The time: spring 1943.

A few months earlier, on 2 February 1943, the German 6th Army surrendered at Stalingrad. Some 90,000 German soldiers were taken prisoner; the total number of German losses may have been around 270,000. Perhaps even more ominously for the Germans, their remaining forces in the region, sunk as they were in sleet, snow and atrociously low temperatures, were confused, demoralized and disorganized. Nevertheless, thanks very largely to a single officer, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, the German front held. Many considered him the mastermind behind the operation (“Case Yellow”) that had brought down France back in 1940; in truth, though, his performance on this occasion was even better.

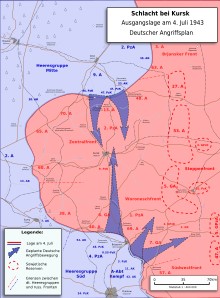

By March/April the antagonists were once again facing each along more or less cohesive lines. At the center of the front, which reached from Leningrad to the Black Sea, was a huge Russian salient measuring some 250 kilometers from north to south and 150 kilometers from east to west. It was in and around this salient that the Red Army and the Wehrmacht deployed their most powerful formations, numbering about a million men on each side. In ordering the offensive Hitler was hoping to pinch off the salient while destroying as many Soviet as possible. That done, his troops would be free to move in any direction they chose. North towards Moscow, important because of its railway crossings and its arms industry; east to the Volga through which passed much of the American and Brutish aid to the USSR; and south toward Rostov, the key to the Caucasus where the Red Army got his oil.

It was not to be. Thanks partly to the fact that the German plans fell into Soviet hands, partly to Hitler’s hope that, by postponing the offensive, he would be able to bring up more of his new Panther and Tiger tanks, the Red Army was ready. Starting on 5 July, a week’s ferocious fighting did not lead to the desired result, forcing the Fuehrer to order his commanders to suspend their advance and switch to the defensive instead. But even if it had succeeded it would probably not have brought the Soviet Union to its knees. Given that, by this time, Stalin’s huge domain was fully mobilized and much of its industry evacuated hundreds of kilometers east towards the Urals, well beyond the Wehrmacht’s reach.

Almost exactly eighty years have passed. The forces on both sides are much smaller, so much so that they cannot form cohesive fronts but seem to be distributed in penny packets all over the huge theater of operations. However, the overall strategic situation is not dissimilar. This time it is the Ukrainian armed forces that are said to be preparing for a spring offensive. This time too any offensive that may be in the making keeps being postponed, allegedly because the Ukrainians are still waiting for sufficient weapons—tanks, ammunition, drones and anti-aircraft defenses—to arrive from the West. Whether the Ukrainians are going to attack eastward towards the Donbas and its industry, or southward, with the objective of cutting the narrow land corridor leading from the Donbas to the Russian-occupied Crimea, remains unknown. Finally, in 2023 as in 1943, whether a Ukrainian offensive, even one that is tactically and operationally successful, can be pushed to the point where the Kremlin is forced to give up the fight remains questionable.

Right or wrong, no one seems to be talking about a new Russian offensive. Possibly this is because Putin cannot muster the necessary forces; however, judging by events since 24 February 2022, such an offensive, even if it can be launched, is most unlikely to lead to a quick victory either. Overall the most likely outcome is a prolonged battle of attrition similar, say, to the one Iranians and Iraqis waged against each other from 1980 to 1988. And which will most likely be decided, not by events on the battlefield but by one of the two sides saying, perhaps after a more or less legitimate, more or less conspirational and violent, change of government: enough is enough.