As Mark Twain, who is supposed to have said everything, is supposed to have said, Germany is the most beautiful country in the world. Let me repeat: Not just in Europe, but in the world. Especially in summer, the season my wife and I like to visit. From the Baltic in the north to the Alps in the south, from the flat, wide-open spaces in the northeast to the more densely settled, often hilly, provinces in the southwest, no country has more variety.

And, yes, the Netherlands and Switzerland apart no country is better looked after by its citizens. The mountains. The “fairy-tale woods,” as the American writer Erika Jong, who spent some time living in Heidelberg and knew Germany well, called them back in 1970. The clean rivers and equally clean lakes (when I first visited Potsdam a quarter century ago I was told they were all contaminated and that I couldn’t swim in them; since then, what a wonderful change!) The infinitely numerous hiking trails that lead everywhere and nowhere. Such as one can walk not only freely—this is not the US, where much of the countryside is privately owned and closed to visitors and where you never know when a roughneck with a gun will pop up to chase you away. But in the kind of safety that, even today, never ceases to astonish and delight visitors.

I have heard it said that Gunther Grass once wrote that, if God had shat concrete, the outcome would have been Frankfurt (sorry, guys, I cannot find the reference). I do not know Frankfurt well; but I know that, applied to other German cities, the comment is highly unfair. Berlin’s Potsdammer Platz apart, you do not often meet the kind of stunning postmodernist architecture you see elsewhere. What you do see, and a lot of it too, are the parks and greenery that grace them. Berlin itself seems to have fewer skyscrapers per square kilometer than any other modern capital. Those it does have are hardly more than 100 meters tall. And then there are the tree-lined streets, including the one in Zehlendorf where my wife if and I spent much of the summer of 2018. And I am not talking just of the major cities. To the contrary: in my view it is precisely the smaller ones, such as Freiburg and Heidelberg, Konstanz and Trier, Bonn and Luebeck, that offer those who live in them a quality of life as good as, if not better than, any other places in the world.

*

Historically, Germany has always been a decentralized country. To be sure, there was an emperor. However, his powers were kept in check by the two higher estates, the religious and the lay, as well as the numerous “free” cities scattered all over. As the peregrinations of many emperors down to Karl V show, moreover, for a long time there was no proper capital. Instead, emperors spent their time moving from one town to another, mounting so-called joyous entries and having fun with the local women who were put at their disposal.

Whether or not, in the modern world, federalism is a good thing I shall not discuss here. What I do want to point out is the fact that, with bishops and princes and urban patricians competing to see who could build the most splendid court, no single city, not even Berlin, (and, before Berlin, Vienna) has ever been able to dominate the country’s cultural life as London and Paris do in England and France respectively. The results are, or should be, obvious to the most casual visitor. Almost anywhere one goes, one finds fine public buildings, operas, theaters, musical performances, and museums whose treasures in spite of the destruction and looting occasioned by World War II, match whatever is available abroad. Even a small (population, 54,000) provincial city such as Greifswald, which I happen to have visited recently, has a surprising number of them.

*

Given all this, when I feel like teasing my German friends I ask them why, with such a splendid country to call their own, their early twentieth-century ancestors in particular have so often invaded their neighbors! But let’s get serious. Nietzsche, himself a German (though he did not like Germans one bit) once wrote that, at bottom, history is nothing but a list of atrocities. Such as have been carefully pruned to suit the historian and his readers and chronologically arranged, one by one, like beads on a string. That is as true of Germany as it is of all other nations; including, in a comparatively minor but unfortunately not negligible way, the one to which I myself belong. However, until 1933, on which more in a moment, the list of German atrocities was no worse than that of most other countries.

There were even times when things German were held up as examples for others to follow. In antiquity, the rude, but honest and courageous, tribesmen and tribeswomen the Roman historian Tacitus wrote about. During the late middle ages and the Renaissance, the flourishing cities of northern and southern Germany. In the sixteenth century, Luther who first rid the Church of much accumulated mumbo-jumbo and then forced it to reform itself until it became halfway decent. In the eighteenth century, the German Enlightenment and its mighty contribution to world literature, philosophy, etc. In the nineteenth century, “Athens on the Spree.” The proverbial country of poets and thinkers. To say nothing of the unexcelled line of musicians reaching from Bach to Wagner and Strauss.

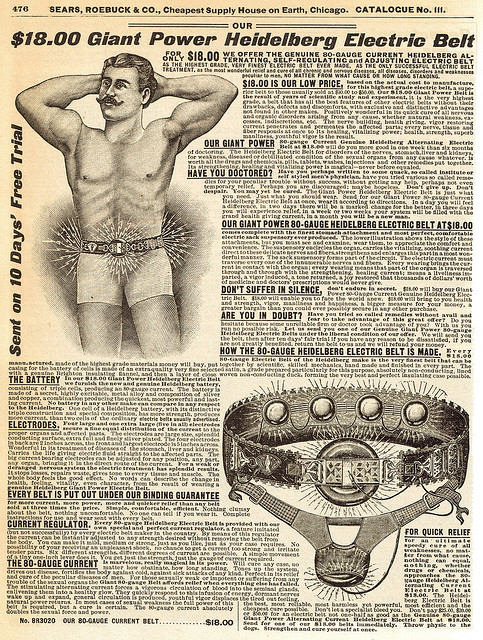

The list does not end there. It also includes the modern German university system, the house of whose founder, Wilhelm von Humboldt, my wife and I went to visit the other day. German science, and medicine (from about 1860 to 1933). The best organized, most efficient, and least dishonest civil service and judiciary (during the same period). For those who care about such things, the best organized, most powerful single army the world had ever seen (ditto). But why go on? I happen to own a replica of an old Sears and Roebuck catalogue. Printed and distributed in 1902, hundreds of pages thick, it contains descriptions and drawings of thousands of items. Starting with women’s underwear—this was before brassieres were invented—passing though buggies (light vehicles, drawn by a single horse or, sometimes, a goat or a dog!)—and ending with grand pianos. Leafing through it, one cannot escape the impression that anything German was considered best. Including, besides magnifying glasses, something known as a Heidelberg belt; a battery-operated device into which one sticks one’s penis by way of a cure for impotence.

*

In brief, even some of Germany’s enemies were sometimes prepared to praise it. Enter the Nazis. In Grass’ novel, The Tin Drum, they figure as eels emerging out of the skull of a dead horse rescued from the sea. At first people are disgusted. Later they get used to them, cook them, and eat them with some relish. Grass’ reputation is well deserved; no better way of showing how unsavory, how revolting, the Nazis were has ever been put first on paper and then on film as well.

To be sure, the Nazis were disgusting. Ironically, though, from Hitler down one of their key objectives—on par, I’d say, with gaining Lebensraum and getting rid of the Jews by exterminating them if necessary—was to build a wholesome world. One cleansed of democracy, an imported system which was not only slow and cumbersome but, by putting quantity ahead of quality, went against what Hitler personally saw as the eternal laws of nature. One cleansed both of communism and of the harshest, most exploitative, forms of capitalism. One cleansed of all sorts of incurably diseased people who were to be given a mercy death in the form of a lethal injection. Once cleansed of “degenerate” art which, deliberately designed to weaken the human spirit, produced not masterpieces but unseemly monsters. One cleansed of feminism, the product of the twisted brains of unnatural women who did not want or could not have children and were effectively eugenic duds. And cleansed of Jews, the race whose members united in their own persons all these bad things and then some; or so the Nazis claimed.

*

Years ago, visiting the former concentration camp at Dachau, I came across a sign, not far away. Search as I did I could not locate it on Google; whether it is still there I do not know. So let me paraphrase from memory. Visitor, it said, do not forget that our town, Dachau, existed a thousand years before anyone ever heard of Hitler, National Socialism, concentration camps, etc. (it did; the first mention goes back to 805 CE, but the site was inhabited two thousand years earlier than that). So please, the sign went on, do not judge us solely through the prism of those terrible twelve years. Fair enough, many people would say. Me included.

The problem is that it does not work that way. To be sure, the Nazi years only took up a tiny part of German history. Arguably, compared with such events as the ascent of Otto I in 962, the issuing of the Golden Bull (1356), the Reformation (1517) the Thirty Years War (1618-48), and the unification of Germany in 1871 it is not even the most important part. Yet it is this tiny part that has taken over. As the years went by, instead of fading away as most history does, it started forming a kind of telescope through which both the past and the future of Germany are seen.

The debate about the so-called German Sonderweg, meaning a road that is different or special, went on for decades. Works originating in, or dealing with, the pre-1945 period raise the question as to whether A, B, C or D was or was not a forerunner of, or at least had some affinities with, the extreme evil that was National Socialism. Almost without exception, those originating in, or dealing with, the post-1945 period are judged by whether or not they show traces of that dread disease.

Do I have to add that anything originating during the Nazi period itself is bad by definition? Not just the buildings and the Autobahnen. But also the often astonishing technological progress made. To mention but four examples, the helicopters, jet aircraft, cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles which the Germans were the first to build. And the sincere, if ideologically tainted, efforts to keep the environment clean, combat smoking and breast cancer, and protect women so they could give healthy offspring to the Reich.

The Nazis’ attitude to art was notoriously intolerant. There are even stories about Hitler personally destroying some paintings he did not like by kicking holes in them! But that is only half of it. Far from being indifferent to art as many garden-variety politicians have always been and still are, he believed art could and should play a critically important role in educating the German people the way he wanted to educate it. To this end he and his paladins (mainly, in this field, Goebbels and Rosenberg) did his best to encourage artists, give them commissions, award prizes, and the like. Many tens of thousands of artworks were created, bought and put on display either in private residences or in public. Some were even put on parade! After the war practically all this art disappeared into the museums’ cellars where, like a bone stuck in somebody’s throat, it still remains. Is that because it is unsightly? Or, to the contrary, because of the fear that the wholesome world (heile Welt) it tried to create might not only attract countless visitors but enthuse them too?

At the focus of all these problems is the prohibition on the public display of the swastika. Writing as a Jew whose family went through the Holocaust, I find this prohibition completely justified. Yet I cannot keep noting that it gives rise to occasional absurdities. In other countries World War II- military equipment, uniforms, etc, can be freely displayed. Not so in Germany, where it must first of all be sterilized (recently, at the Luftwaffe historical museum at Gatow, I saw the anti-swastika rule being slightly violated; how that came about I do not know). The English version of my own book, Hitler in Hell, has a burning swastika on the cover. As a result, it has been banned from being sold in Germany; yet I would have thought that the title and the image between them demonstrate my opinion of him clearly enough.

*

Outside Germany the situation is even worse. At You Tube documentaries showing the Nazi years are enormously popular in spite of their often mediocre quality. Out of every ten works on German history that are published in English, perhaps nine deal with that period (as, of course, this essay also does). In almost any country one may visit, one only has to mention the word Nazi to fill the air with electricity. There is even something called, and not just jokingly, Godwins’s Law; whenever two persons argue for more than a few minutes, at least one of them is going to call the other a Nazi.

Living in Germany, even for fairly short periods as I did, one sees the consequences all around. I do not mean just the countless memory sites, museums, exhibitions, day tours, and the like that focus on the years from 1933 to 1945. Partly in the hope of providing Mahnung, which is the official rationale; and partly because the public cannot have enough. I mean the fact that, Potsdam’s Schillerplatz used to be called Adolf Hitlerplatz (it was, in fact, built under his rule). On Berlin’s Fehrbelliner Platz, where I have often dined with my friends, the buildings erected for the Nazi Labor Front sill show the spots where the original swastikas were chiseled off the walls. I mean the kind of day-to-day politics in which the Left, (too often, falsely) pretending to take the moral high ground, accuses the Right of being Nazis and the Right is constantly forced to defend itself against that charge.

Fear of being considered Nazi also does much to explain German foreign policy. Starting with the rather exceptional, not to say strange, relationship between Germany and Israel; when former Chancellor Konrad Adenauer visited Jerusalem I 1966 I myself had occasion to witness the birth of that relationship, complete with the demonstrations against it. Passing through the one between Berlin and Europe’s remaining capitals, and ending with the way refugees are treated. Aliis licet, non tibi; what others are allowed to do, you Germania, for historical reasons so obvious that they do not have to be pointed out, cannot.

*

Let me end by saying that, when I first visited Germany back in 1976, it was all but impossible to go through a single day without some German one had met, upon learning that I was an Israeli, starting to explain that he or she had not done anything wrong. Ditto for their family, town, region, etc; I often wondered whether there had been any Nazis in Germany and how, in that case, they have succeeded in hiding so well. My wife, who was living in Germany at the time but whom I had not yet met, had the same experience. The constant apologies made it very hard to strike up a friendship! Those days, thankfully, are gone. Today and for years past strangers—shopkeepers, waiters, hotel owners, and the like—who learn that my wife and I are Israeli mostly react in a very favorable way.

Of my closer acquaintances, not one is old enough to have reached maturity during those terrible years. The oldest is 83; how old he was back in 1945 you can figure out for yourself. He is a former East German, retired, professor of economics. When still in his prime his hobby was writing illustrated books on ocean-going ships. Now he keeps busy by gardening; he loves cats and has a good sense of humor. He is also a kind man. For almost twenty years, no cloud however small has ever disturbed our sky. Others are much younger. Often so much so that not only they but their parents and even grandparents too cannot have done anything wrong.

The problem is that, far from creating a wholesome world, the Nazis have polluted both the country and its people for all future to come. And much as I feel for my dear German friends, there is nothing I or anyone else can do about that.