Like almost all other Westerners, at the time the Russian-Ukrainian War broke out in February 2022 I was convinced that the Russians would fail to reach their objectives and lose the war. Putting the details aside, this prediction was based on the following main three pillars.

First, the numerous failures, after 1945, of modern, state-run armed forces to cope with uprisings, insurgencies, guerrilla warfare, terrorism, asymmetrical warfare, and any number of similar forms of armed conflict. Think of Malaysia—yes, Malaysia, so often falsely claimed by the British as a victory. Think of Algeria, think of Vietnam, think of Iraq, think of dozens of similar conflicts throughout Asia and Africa. Almost without exception, it was the occupiers who lost and the occupied who won.

Second, the size of Ukraine’s territory and population made me and others think that Russia had tried to bite off more than it could swallow. The outcome would be a prolonged, very bloody and very destructive, conflict that would be decided not so much on the battlefield but by demoralization both among Russia’s troops and among its civilian population. As, indeed, happened in 1981-1988 when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, only to get involved in a lengthy counter-insurgency campaign that ended not just in military defeat on the ground but in the disintegration of the Soviet Union. This line of reasoning was supported by the extreme difficulty the Russians faced before they finally succeeded in bringing Chechnya, a much smaller country, to heel.

Third, plain wishful thinking—something I shared with most Western observers. Including heads of state, ministers, armed forces, intelligence services, and the media.

Since then four very eventful months have passed. As they went on, the following factors have forced me to take another look at the situation.

First, the Ukrainians are not fighting a guerrilla war. Instead, as the list of weapons they have asked the West to provide them with shows, they have been trying to wage a conventional one: tank against tank, artillery barrel against artillery barrel, and aircraft against aircraft. All, apparently, in the hope of not only halting the Russian forces but of expelling them. Given that the Russians can fire ten rounds for every Ukrainian one, such a strategy can only be a sure recipe for defeat.

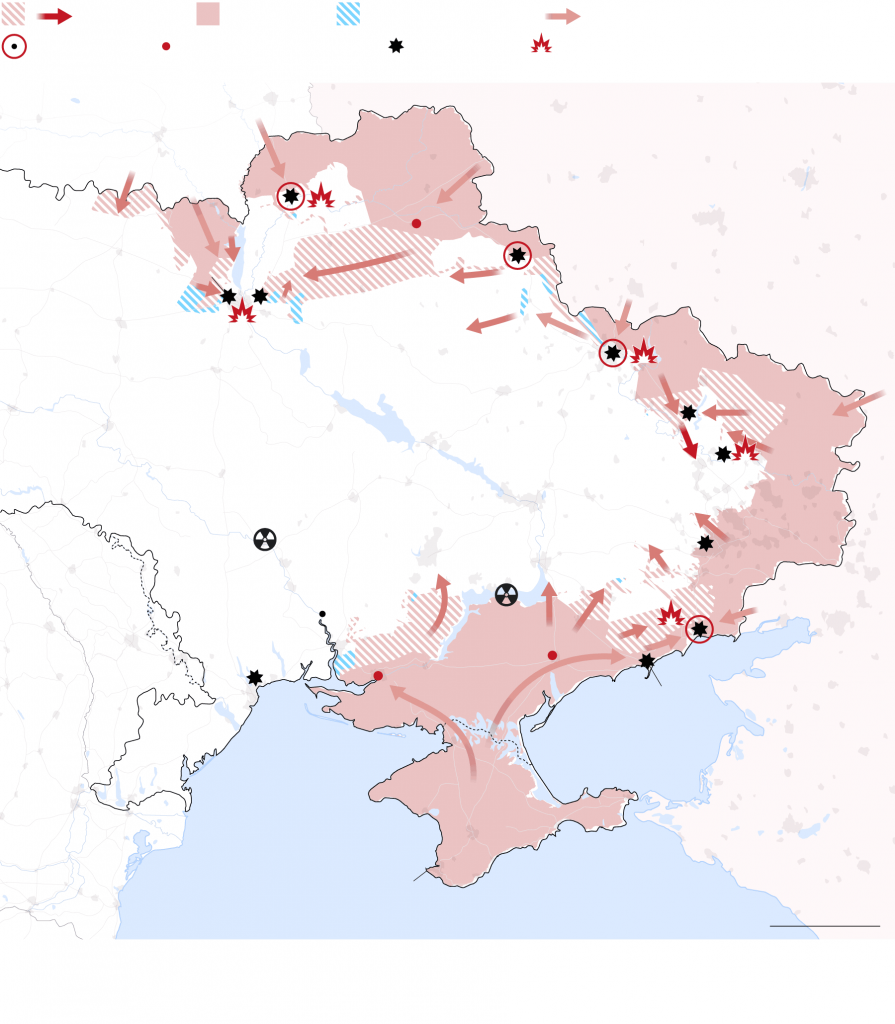

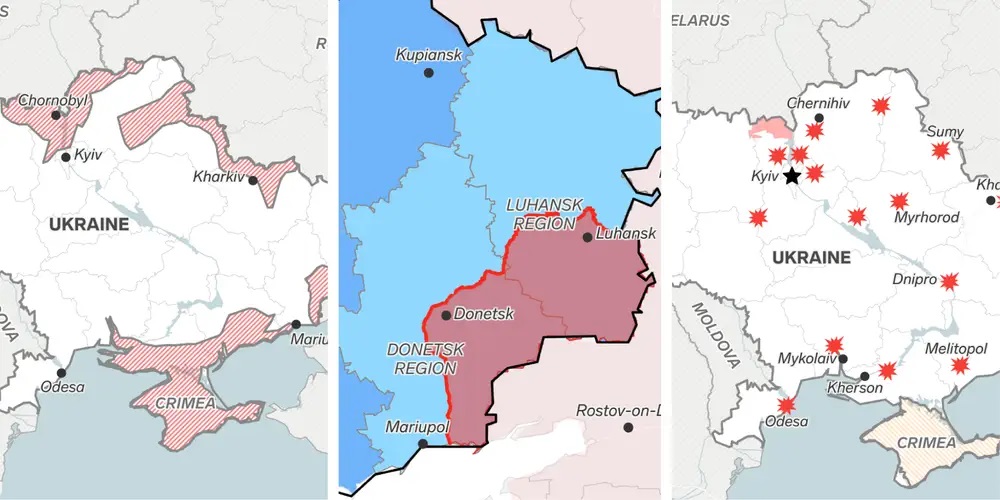

Second, a change in Russian tactics. Greatly underestimating their enemies, the Russians started the war by attempting a coup de main against the center of Ukrainian power at Kiev. When this failed it took them some time to decide what to do next; they may even have replaced a few of their top ranking generals. But then they regrouped and switched to the systematic reduction of Ukrainians cities and towns. Much as, in 1939-40, Stalin and his generals did to Finland. As in both that war and World War II as a whole they resorted to what has traditionally been their most powerful weapons, i.e massed artillery. It now appears that the change enabled them to reduce their losses to levels that they can sustain for a long time. Perhaps longer than the Ukrainians who, by Zelensky’s own admission, are losing as many as 100-200 of their best fighters killed in action each day.

Third, Western military technology, especially anti-aircraft weapons, anti-tank weapons, and drones may be excellent. However, limited numbers, the result of years and years of parsimony and the belief that war in Europe had become impossible, plus the need to retrain the relevant Ukrainian personnel, means that it has been slow to arrive in the places where it is most needed. Not to mention the fact that, whereas the Russians are fighting close to home, NATOs lines of communication stretch over hundreds of miles all the way from Ukraine’s borders with Poland, Slovakia and Romania in the west to the Donbas in the east. Almost all the terrain in between is flat, devoid of shelter, and thinly populated. Meaning that it is ideal for the employment of airpower, precisely the field in which Russian superiority over Ukraine is most pronounced.

Fourth, strict censorship is making the impact of Western economic sanctions on Russia’s population hard to asses. If there is any grumbling, it is being energetically suppressed. Meanwhile, a look at the macroeconomics seems to show that Russia is coping much better than many Westerners expected. Gold reserves have been inching up, enabling Putin to link his currency to gold—the first country to do so since Switzerland went in the opposite direction back in 1999. The Ruble, which early in the war came close to collapse, is back to a seven-year high against the dollar, trend upward. Given the fall in imports as well as the tremendous rise in energy prices, more money is flowing into Russia’s coffers than ever before. Most of that money comes from selling energy, foodstuffs and raw materials to countries such as China and India. China in turn is now the world’s number one industrial power; once its current troubles with COVID-19 are over, it should be well able to provide Russia with almost any kind of industrial product it needs, and do so for a long time to come.

Fifth, the economic impact of the war on the West has been much greater than anyone thought. Saving Ukraine form Russian’s clutches is not like doing the same with Afghanistan. On both sides of the Atlantic inflation is higher than it has been at any time since 1980. Especially in regard to energy, which Russia is refusing to provide Europe with, it is giving rise not just to confusion but to some real hardship. Should it continue, as it almost certainly will, it will give rise to growing popular discontent with the war and demands that their countries’ involvement in it be reduced or brought to an end. Even if that end means abandoning Ukraine and allowing Putin to have his way with it.

Last not least, beginning with the Enlightenment the West has long preened itself on being a fortress where liberty, law and justice prevail. Now the repeated, highly publicized, requisitioning of the property of so-called oligarchs is beginning to make some people wonder. First, no one knows what an “oligarch” is. Second, the fact that some “oligarchs” have been in more or less close touch with Putin over the years does not automatically turn them into criminals. Third, supposing they are criminals, it is not at all clear why they were left alone for so long and only began to be targeted after the war broke out. Could it be that, in combating the oligarchs, the West is undermining the justice of its cause?

To be sure, we are not there yet. But as growing number of statements that the war is going to be a long one show, it is now primarily a question of who can draw the deepest breath and hold out the longest. And when it comes to that, Russia’s prospects of coming out on top and obtaining a favorable settlement are not at all bad.

Now that the initial momentum has been spent and replaced by attrition (on both sides), it is possible to speculate about the outcome of the war everyone has been talking about for the last few months.

Now that the initial momentum has been spent and replaced by attrition (on both sides), it is possible to speculate about the outcome of the war everyone has been talking about for the last few months.

First, a disclaimer. President Putin has neither been whispering in my ear nor appearing in my dreams. Nor did his advisers, senior or junior, civilian or military, official or unofficial. Nor, on the other hand, do I necessarily trust any of the usual sources mentioned by Western media. Meaning, their own countries’ intelligence services, the reports of their journalists and cameramen on the ground, tales told by Ukrainian soldiers, tales told by local Ukrainians, tales allegedly originating in Russian POWs, and so on. All these different sources, and many others besides, have their limits. Many also have an ax to grind: either to deny Russian atrocities or to emphasize them as much as possible. It is as people say. In war, any war without exception, the first casualty is the truth.

First, a disclaimer. President Putin has neither been whispering in my ear nor appearing in my dreams. Nor did his advisers, senior or junior, civilian or military, official or unofficial. Nor, on the other hand, do I necessarily trust any of the usual sources mentioned by Western media. Meaning, their own countries’ intelligence services, the reports of their journalists and cameramen on the ground, tales told by Ukrainian soldiers, tales told by local Ukrainians, tales allegedly originating in Russian POWs, and so on. All these different sources, and many others besides, have their limits. Many also have an ax to grind: either to deny Russian atrocities or to emphasize them as much as possible. It is as people say. In war, any war without exception, the first casualty is the truth.

The war in Ukraine goes on and on. Though analysts are as numerous as flies on a heap of you know what, the truth is that one knows how it is going to end. Such being the case, I want to put my latest thoughts on record.

The war in Ukraine goes on and on. Though analysts are as numerous as flies on a heap of you know what, the truth is that one knows how it is going to end. Such being the case, I want to put my latest thoughts on record.