How Much is Enough was the title of a 1971 volume published by the RAND (Research and Development) Corporation, an American think-tank with close ties to the United States Air Force which provided the funding. The authors, A. C. Enthoven and K. V. Smith, were both veterans of the Pentagon where they had worked for President Johnson’s Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara. Both were experts on systems analysis. At that time it was a fairly new and exciting discipline that sought to subject as many problems as possible to mathematical analysis; including not just military problems but such as comprised health services, education, transportation and the like..

Some of the most important problems, taking up a considerable part of the book, concerned what people called the nuclear strategic balance between the US and the USSR. What, precisely were the objectives of building up America’s nuclear arsenal? How many nuclear warheads and their delivery vehicles would be needed to deter the USSR from launching an attack? Supposing deterrence failed and nuclear war broke out, what did victory mean and how to ensure it went to America? Should there be one kind of missile/bomber aircraft or a mix of several different ones? If the latter, then how many of each kind? How to best use them, and against what targets? How many, if any, should be kept in reserve? What was the best way to render them invulnerable to a Soviet attack? And so on and so on.

Today in NATO’s capitals—Washington, London, Paris, Berlin, and to some extent less important ones too—somewhat similar questions are being asked. With this difference that, as far as the public record is concerned, the issue is not nuclear weapons but how many conventional ones, specifically tanks, to send to Ukraine’s aid. Where and how to employ them, and so forth. It goes without saying that the discussions are highly classified. Still it is possible to draw up a list of some of the most important questions that, in one combination or another, will have to be resolved before a decision is make.

- The nature of the mission. Is it to be defensive—just enabling Zelensky and his men to hold out until something gives—or offensive—liberating the Donbas and the Crimea? Suppose the latter is the case and these objectives are attained but the Russians still keep on fighting—as they did in 1812 and, in different ways, both in 1917-18 and 1941—what then? Note that, as a general rule, fighting on the defensive is easier and requires fewer forces than going on the offensive does.

- Losses. How many tanks are the various NATO countries prepared to lose, and in what time frame?

- Availability and production. Not only are at least some tanks going to be lost, but they are expensive beasts. A brand-new Leopard II costs about 15 million Euro. As a result, no country has an unlimited supply of the most modern tanks in particular. How many tanks can the NATO countries send into the field without putting their own security at too great a risk? How many can be sent now? How many in the future? How long will producing and fielding new ones take?

- Substitution. Suppose NATO country A sends some tanks to fight in Ukraine. Will the rest make up for the deficit?

- As the Russian invaders have discovered to their cost, and contrary to their image as kings of the battlefield, tanks are vulnerable. To other tanks. To certain kinds of anti-tank weapons. To drones, especially such as are used to attack them from above rather than from the front where tanks carry their thickest armor. Such being the case, tanks rarely operate on their own but are regularly escorted by other forces, primarily artillery, anti-tank missiles, anti-aircraft defenses, and engineers. How many of those can be sent now? How many in the future? How long will producing and fielding them take? How long will training Ukrainian troops in operating the tanks take?

- How many tanks can be supported and kept supplied? Bear in mind that tanks and their supporting forces require huge amounts of supplies. Depending on the terrain as well as the kind of operation, a modern battle tank such as the Leopard II will easily consume 3.4 L/km on road and 5.3 L/km off it. Plus ammunition, plus spare parts. Plus, in case they fight on the defense, various engineering materials. Plus all kinds of other supplies (food, water, medical supplies) which, though small in weight, are must arrive at the right place at the right time. To aggravate the problem, tanks rarely remain at the same place for long, forcing the logistic tails to follow them.

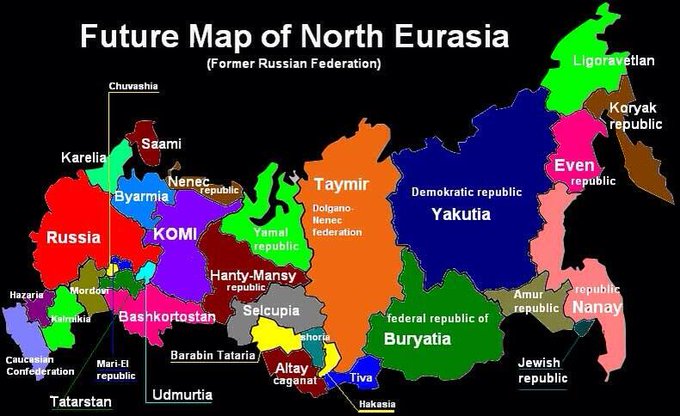

- What are the Russians likely to do in response? Open a new front by dragging Belarus into the war? Start at least some operations in NATO territory? Mobilize even more troops? Resort to tactical nuclear weapons?

- Finally, politics. Building a model of what a nuclear exchange might be like, Enthoven and Smith all but ignored politics. Indeed their tacit (but far from unreasonable) assumption was that, in that case, there would be no politics. However, the war in Ukraine is not a one-time spasm. If only for that reason, NATO planners cannot ignore them. How much political capital are the various countries, both leaders and populations, prepared to spend in assisting Ukraine? For how long?

In the long run it is this question that is likely to be the most important of all.

In theory, wars should end when the defeated have no one left to fight and the victors can do whatever they likes. In practice, many if not most wars do not end in this way. As the end approaches and few doubts remain concerning the outcome, the loser will try and get the best terms he can; whereas the victor may be tempted to spare himself further effort, treasure and blood. Another possibility is for stalemate to prevail; causing both sides to have second thoughts about whether their goals can in fact be achieved and start to look for a way out.

In theory, wars should end when the defeated have no one left to fight and the victors can do whatever they likes. In practice, many if not most wars do not end in this way. As the end approaches and few doubts remain concerning the outcome, the loser will try and get the best terms he can; whereas the victor may be tempted to spare himself further effort, treasure and blood. Another possibility is for stalemate to prevail; causing both sides to have second thoughts about whether their goals can in fact be achieved and start to look for a way out.

To most people, whether or not a ruler or country “uses” nuclear weapons is a simple choice between either dropping them on the enemy or not doing so. For “experts,” though, things are much more complicated (after all making them so, or making them appear to be so, is the way they earn their daily bread). So today I am going to assume the mantle of an expert and explain some of the things “using” such a weapons might mean.

To most people, whether or not a ruler or country “uses” nuclear weapons is a simple choice between either dropping them on the enemy or not doing so. For “experts,” though, things are much more complicated (after all making them so, or making them appear to be so, is the way they earn their daily bread). So today I am going to assume the mantle of an expert and explain some of the things “using” such a weapons might mean.