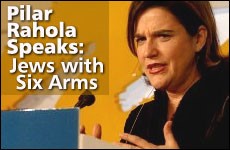

by Pilar Rahola

Why do so many intelligent people, when talking about Israel, suddenly become idiots?

This speech was given December 16, 2009 at the Conference in the Global forum for Combating Anti-Semitism in Jerusalem. Pilar Rahola is a Spanish Catalan journalist, writer, and former politician and Member of Parliament, and member of the far left.

A meeting in Barcelona with a hundred lawyers and judges a month ago.

They have come together to hear my opinions on the Middle-Eastern conflict. They know that I am a heterodoxal vessel, in the shipwreck of “single thinking” regarding Israel, which rules in my country. They want to listen to me, because they ask themselves why, if Pilar is a serious journalist, does she risk losing her credibility by defending the bad guys, the guilty? I answer provocatively – You all believe that you are experts in international politics when you talk about Israel, but you really know nothing. Would you dare talk about the conflict in Rwanda, in Kashmir? In Chechnya? – No.

Cultured people, when they read about Israel, are ready to believe that Jews have six arms.

They are jurists, their turf is not geopolitics. But against Israel they dare, as does everybody else. Why? Because Israel is permanently under the media magnifying glass and the distorted image pollutes the world’s brains. And because it is part of what is politically correct, it seems part of solidarity, because talking against Israel is free. So cultured people, when they read about Israel, are ready to believe that Jews have six arms, in the same way that during the Middle Ages people believed all sorts of outrageous things.

Bottom of Form

The first question, then, is why so many intelligent people, when talking about Israel, suddenly become idiots. The problem that those of us who do not demonize Israel have, is that there exists no debate on the conflict. All that exists is the banner; there’s no exchange of ideas. We throw slogans at each other; we don’t have serious information, we suffer from the “burger journalism” syndrome, full of prejudices, propaganda and simplification. Intellectual thinkers and international journalists have given up on Israel. It doesn’t exist. That is why, when someone tries to go beyond the “single thought” of criticizing Israel, he becomes suspect and unfaithful, and is immediately segregated. Why?

I’ve been trying to answer this question for years: why?

Why, of all the conflicts in the world, only this one interests them?

Why is a tiny country which struggles to survive criminalized?

Why does manipulated information triumph so easily?

Why are all the people of Israel, reduced to a simple mass of murderous imperialists?

Why is there no Palestinian guilt?

Why is Arafat a hero and Sharon a monster?

Finally, why when Israel is the only country in the World which is threatened with extinction, it is also the only one that nobody considers a victim?

I don’t believe that there is a single answer to these questions. Just as it is impossible to completely explain the historical evil of anti-Semitism, it is also not possible to totally explain the present-day imbecility of anti-Israelism. Both drink from the fountain of intolerance and lies. Also, if we accept that anti-Israelism is the new form of anti-Semitism, we conclude that circumstances may have changed, but the deepest myths, both of the Medieval Christian anti-Semitism and of the modern political anti-Semitism, are still intact. Those myths are part of the chronicle of Israel.

For example, the Medieval Jew accused of killing Christian children to drink their blood connects directly with the Israeli Jew who kills Palestinian children to steal their land. Always they are innocent children and dark Jews. Similarly, the Jewish bankers who wanted to dominate the world through the European banks, according to the myth of the Protocols, connect directly with the idea that the Wall Street Jews want to dominate the World through the White House. Control of the Press, control of Finances, the Universal Conspiracy, all that which has created the historical hatred against the Jews, is found today in hatred of the Israelis. In the subconscious, then, beats the DNA of the Western anti-Semite, which produces an efficient cultural medium.

But what beats in the conscious? Why does a renewed intolerance surge with such virulence, centered now, not against the Jewish people, but against the Jewish state? From my point of view, this has historical and geopolitical motives, among others, the decades long bloody Soviet role, the European Anti-Americanism, the West’s energy dependency and the growing Islamist phenomenon.

But it also emerges from a set of defeats which we suffer as free societies, leading to a strong ethical relativism.

The moral defeat of the left. For decades, the left raised the flag of freedom wherever there was injustice. It was the depositary of the utopian hopes of society. It was the great builder of the future. Despite the murderous evil of Stalinism’s sinking these utopias, the left has preserved intact its aura of struggle, and still pretends to point out good and evil in the world. Even those who would never vote for leftist options, grant great prestige to leftist intellectuals, and allow them to be the ones who monopolize the concept of solidarity. As they have always done. Thus, those who struggled against Pinochet were freedom-fighters, but Castro’s victims, are expelled from the heroes’ paradise, and converted into undercover fascists.

This historic treason to freedom is reproduced nowadays, with mathematical precision. For example, the leaders of Hezbollah are considered resistance heroes, while pacifists like the Israeli singer Noa, are insulted in the streets of Barcelona. Today too, as yesterday, the left is hawking totalitarian ideologies, falls in love with dictators and, in its offensive against Israel, ignores the destruction of fundamental rights. It hates rabbis, but falls in love with imams; shouts against the Israeli Defense Forces, but applauds Hamas’s terrorists; weeps for the Palestinian victims, but scorns the Jewish victims, and when it is touched by Palestinian children, it does it only if it can blame the Israelis.

It will never denounce the culture of hatred, or its preparation for murder. A year ago, at the AIPAC conference in Washington I asked the following questions:

Why don’t we see demonstrations in Europe against the Islamic dictatorships?

Why are there no demonstrations against the enslavement of millions of Muslim women?

Why are there no declarations against the use of bomb-carrying children in the conflicts in which Islam is involved?

Why is the left only obsessed with fighting against two of the most solid democracies of the planet, those which have suffered the bloodiest terrorist attacks, the United States and Israel?

Because the left no longer has any ideas, only slogans. It no longer defends rights, but prejudices. And the greatest prejudice of all is the one aimed against Israel. I accuse, then, in a formal manner that the main responsibility for the new anti-Semitic hatred disguised as anti-Zionism, comes from those who should have been there to defend freedom, solidarity and progress. Far from it, they defend despots, forget their victims and remain silent before medieval ideologies which aim at the destruction of free societies. The treason of the left is an authentic treason against modernity.

Israel is the world’s most watched place, but despite that, it is the world’s least understood place.

Defeat of Journalism. We have more information in the world than ever before, but we do not have a better informed world. Quite the contrary, the information superhighway connects us anywhere in the planet, but it does not connect us with the truth. Today’s journalists do not need maps, since they have Google Earth, they do not need to know History, since they have Wikipedia. The historical journalists, who knew the roots of a conflict, still exist, but they are an endangered species, devoured by that “fast food” journalism which offers hamburger news, to readers who want fast-food information. Israel is the world’s most watched place, but despite that, it is the world’s least understood place. Of course one must keep in mind the pressure of the great petrodollar lobbies, whose influence upon journalism is subtle but deep. Mass media knows that if it speaks against Israel, it will have no problems. But what would happen if it criticized an Islamic country? Without doubt, it would complicate its existence. Certainly part of the press that writes against Israel, would see themselves mirrored in Mark Twain’s ironical sentence: “Get your facts first, then you can distort them as you please.”

Defeat of critical thinking. To all this one must add the ethical relativism which defines the present times: it is based not on denying the values of civilization, but rather in their most extreme banality. What is modernity?

I explain it with this little tale: If I were lost in an uncharted island, and would want to found a democratic society, I would only need three written documents: The Ten Commandments (which established the first code of modernity. “Thou shalt not murder” founded modern civilization.); The Roman Penal Code; and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And with these three texts we would start again. These principles are relativized daily, even by those who claim to be defending them.

“Thou shalt not murder” … depending on who is the target, must think those who, like the demonstrators in Europe, shouted in support of Hamas.

“Hurray for Freedom of Speech!”…, or not. For example, several Spanish left-wing organizations tried to take me to court, accusing me of being a negationist, like the Nazis, because I deny the “Palestinian Holocaust”. They were attempting to prohibit me from writing articles and to send me to prison. And so on… The social critical mass has lost weight and, at the same time ideological dogmatism has gained weight. In this double turn of events, the strong values of modernity have been substituted by a “weak thinking,” vulnerable to manipulation and Manichaeism.

Defeat of the United Nations. And with it, a sound defeat of the international organizations which should protect Human Rights. Instead they have become broken puppets in the hands of despots. The United Nations is only useful to Islamofascists like Ahmadinejad, or dangerous demagogues like Hugo Chavez which offers them a planetary loudspeaker where they can spit their hatred. And, of course, to systematically attack Israel. The UN, too exists to fight Israel.

Finally, defeat of Islam. Tolerant and cultural Islam suffers today the violent attack of a totalitarian virus which tries to stop its ethical development. This virus uses the name of God to perpetrate the most terrible horrors: lapidate women, enslave them, use youths as human bombs. Let’s not forget: They kill us with cellular phones connected to the Middle Ages. If Stalinism destroyed the left, and Nazism destroyed Europe, Islamic fundamentalism is destroying Islam. And it also has an anti-Semitic DNA. Perhaps Islamic anti-Semitism is the most serious intolerant phenomenon of our times; indeed, it contaminates more than 1,400 million people, who are educated, massively, in hatred towards the Jew.

The Jews are the thermometer of the world’s health. Whenever the world has had totalitarian fever, they have suffered.

In the crossroads of these defeats, is Israel. Orphan and forgotten by a reasonable left, orphan and abandoned by serious journalism, orphan and rejected by a decent UN, and rejected by a tolerant Islam, Israel suffers the paradigm of the 21st Century: the lack of a solid commitment with the values of liberty. Nothing seems strange. Jewish culture represents, as no other does, the metaphor of a concept of civilization which suffers today attacks on all flanks. The Jews are the thermometer of the world’s health. Whenever the world has had totalitarian fever, they have suffered. In the Spanish Middle Ages, in Christian persecutions, in Russian pogroms, in European Fascism, in Islamic fundamentalism. Always, the first enemy of totalitarianism has been the Jew. And, in these times of energy dependency and social uncertainty, Israel embodies, in its own flesh, the eternal Jew.

A pariah nation among nations, for a pariah people among peoples. That is why the anti-Semitism of the 21st Century has dressed itself with the efficient disguise of anti-Israelism, or its synonym, anti-Zionism. Is all criticism of Israel anti-Semitism? NO. But all present-day anti-Semitism has turned into prejudice and the demonization of the Jewish State. New clothes for an old hatred.

Benjamin Franklin said: “Where liberty is, there is my country.” And Albert Einstein added: “The World is a dangerous place. Not because of the people who are evil; but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.” This is the double commitment, here and now; never remain inactive in front of evil in action and defend the countries of liberty.

Thank you.

Imagine a number of families—say, ten of them. Some with children and the elderly, some without. Living in the same town, they decide to spend a day together. Fun for the kids, relief for the adults who will not have to ensure that their offspring get bored. Meeting point is at 1100 hours, at place X where there is good parking. From there they plan to drive fifty miles to the beach, arriving at 1200. What could be simpler? But no. Family A finds that the GPS of their car (old and somewhat battered) refuses to work and so informs the rest (some get the message, some don’t). Family B cannot leave their home before grandfather, who is a widower and had lost his false teeth, finds the other set he owns.

Imagine a number of families—say, ten of them. Some with children and the elderly, some without. Living in the same town, they decide to spend a day together. Fun for the kids, relief for the adults who will not have to ensure that their offspring get bored. Meeting point is at 1100 hours, at place X where there is good parking. From there they plan to drive fifty miles to the beach, arriving at 1200. What could be simpler? But no. Family A finds that the GPS of their car (old and somewhat battered) refuses to work and so informs the rest (some get the message, some don’t). Family B cannot leave their home before grandfather, who is a widower and had lost his false teeth, finds the other set he owns.