Speaking of Clausewitz, everyone knows that war is the continuation of politics with an admixture of other means. What few people know is another, no less important, claim by the master. Hidden inside a rather abstruse discussion of the Character der strategischen Verteidigung of his great work) von Kriege (book 6, chapter 5) we read: “der Krieg ist mehr fuer den verteitiger als fuer den Eroberer da, denn der Einbruch hat erst die Vertetigung herbeigefuert und mit ihr erst der Krieg. Der Eroberer ist immer friedliebend…er zoege ganz gern ruhig in unseren Staat ein; damit er dies aber nicht koenne, darum muessen sir den Krieg wollen und also auch veorbereiten.”

As Clausewtiz also says, so it was in his own day when Napoleon regularly made peace offers, provided only he was allowed to keep the countries he had conquered, the crowns he had stolen, and reparations he had extracted. So, too, it was on 19 July 1940 when Hitler, following his victory over France, held a radio address in which he told the British people that he could “see no reason why this war should continue” and appealed to them to make peace with him. Many similar instances could be adduced, but the point is clear.

It did not happen then. Speaking of the Russian-Ukrainian War, neither is it going to happen now. Why? Because mistrust, built up over years of confrontation and fighting, is too great. So the question is, how could the War be brought to an end? It seems to me there are three, and only three, possibilities:

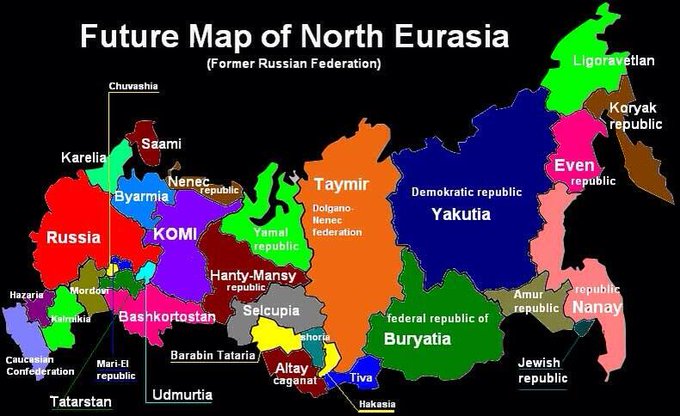

First, a great Ukrainian offensive followed by a complete Russian defeat. With 600,000 square kilometers of land, almost twice the size of united Germany, Ukraine is a large country. But not nearly as large as Russia with its 17.1 million stretching all the way to the Pacific. If only for that reason, and even assuming the West will provide the necessary hardware, a great Ukrainian offensive that will break Russia’s will and force it to sue for peace is almost inconceivable. Such an offensive could only succeed if the government in Moscow were overthrown and a new one put in its place. For such an upheaval to happen Putin would have to be incapacitated by disease, or toppled by a Putsch, or his army would have to disintegrate, or a popular revolution would have to take place first. As of the time of writing, and in spite of occasional claims by Ukrainian spokesmen on one hand and Western intelligence services on the other, there is no sign of any of these things.

Second, a complete Russian victory. Considering the apparent balance of forces, at the beginning of the war many observers, apparently including both Putin and his most important generals, expected Russia to prevail quickly and easily. For which purpose they first mounted an airborne coup de main against Kiev—which failed—and then built a 64-kilometer long convoy of vehicles stretching from the border all the way to the Ukrainian capital and drove towards it four abreast along a single road as if on parade. When that attempt also failed they settled down to a long war of attrition in the east and in the south. One which, thanks partly to Western aid to Ukraine but mainly to the latter’s own remarkable determination to fight and endure, is still ongoing. As things stand at present, though, a complete Russian victory seems quite as unlikely as a complete Ukrainian one.

Finally the only alternative to outcomes (1) and (2) would be to continue a long struggle of murderous attrition similar to the one that has surrounded the city of Bachmut for several months now. Hopefully to be followed, in the end, by some kind of negotiations leading to a compromise. Judging by Putin’s positive reaction to the utterances of his good friend Xi Jinpin, provided only he can point to some achievements he would jump at such an opportunity.

With Ukraine and NATO the situation is more complicated. The former insists on the Russians evacuating all the occupied territories first, and with very good reason. The latter is divided. Some of its members, notably those of Western Europe, realize that a complete victory is impossible and would like the war to end ASAP so they can save as much as possible of the comfortable lifestyle they have led for so long. At least one, Poland, harks back to 1919-20 when it defeated Lenin and the Bolsheviks and would very much like to repeat that performance.

Finally, the US. Not only is it the most powerful NATO member by far, but it enjoys the very great advantage of being far, far away from the center of hostilities. Such being the case it can afford to withdraw from the war, which indeed is just what some Republicans have been calling for. On the other hand, distance also enables it to adopt a more belligerent stance than the West Europeans. Some high-ranking Americans both in- and out of uniform look forward not just to a Russian defeat but to the disintegration of the Russian Federation. Never mind that, as I have argued before in this column, such disintegration would very likely cause much of Asia to go up in flames. And never mind that it would benefit China as much as, if not more than, the US.

How it will work out no one knows, but one thing is clear: in war, expect the unexpected.