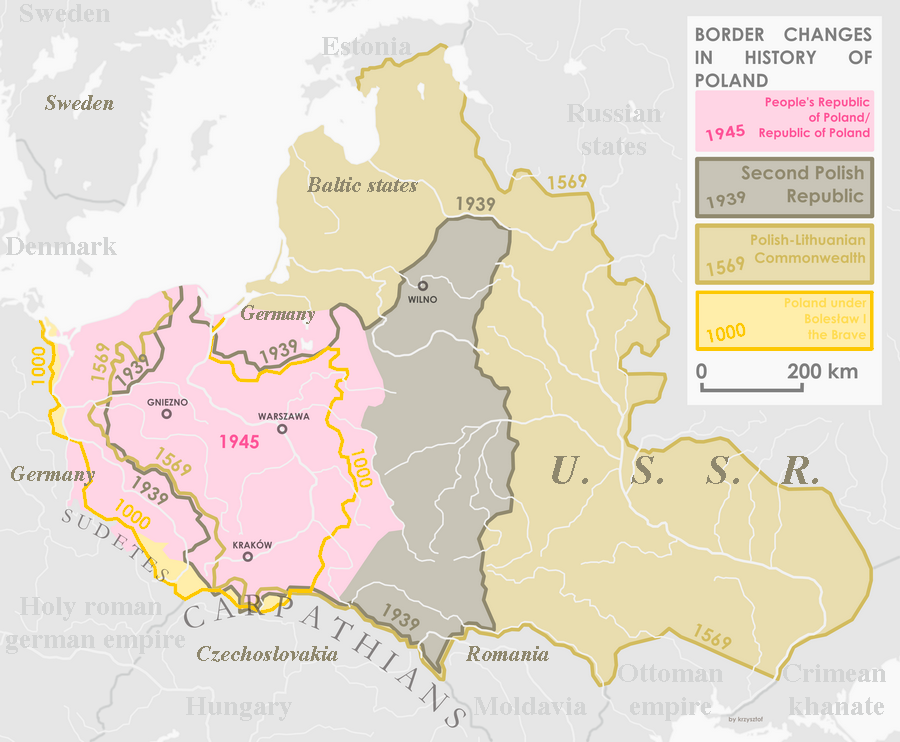

Back in 1938-39, Britain—heartland of the largest empire that ever was—found itself coming under attack in no fewer than three main theaters at once. One, the closest home, was Western Europe and the North Sea where Adolf Hitler was busily at work building up the Third Reich to the point it would be ready to challenge the empire. One consisted of the empire’s communications in the Mediterranean where Benito Mussolini was threatening to take over the Suez Canal, Malta and Gibraltar, “the bars in Italy’s prison,” as he called them. And one in the Far East where a succession of militaristic Japanese governments were preparing to attack Britain’s colonies such as Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore. Things came to a head in September 1939 when Germany, invading Poland, ignited a world war. By the time that war ended six years later Britain was lucky in that it could count itself among the victors. However, its relative power, military industrial and economic, had been shattered and would never recover.

The same year, 1945, also marked the peak of American power. Alone among the main belligerents in World War II—Germany, Britain, France, Italy, the Soviet Union, Japan, and China—the US neither had any part of its territory occupied nor was subject to bombing. Its losses, especially in terms of manpower killed or badly wounded, were also much lighter. Calculated in terms of value, fifty percent of everything was being produced in the U.S. Throughout my own youth in the 1950s and early 1960s, the best most people could say about anything was that it was American. This was as true in Israel, where I lived, as it was in the Netherlands which I occasionally visited; of movies (and movie stars) as of automobiles. As if to crown it all, alone of all the world’s countries the U.S not only possessed nuclear weapons but also, which was almost equally important, a demonstrated willingness to use them as its leaders saw fit.

However, what goes up must go down. In 1949 the Soviet Union tested its first nuke. This proved to be the starting point of a profound, if unexpectedly slow, process of proliferation, each of whose stages marked a downsizing of America’s relative advantage over other countries. Accidentally or not, 1949 also marked the opening of a long period, still ongoing, during which America’s balance of payments has almost never been positive. The decision, made by President Nixon in 1971, to take the US dollar off gold, simply highlighted the change and made the situation worse. Currently the American Government’s debt both to foreign countries and to its own citizens is easily the largest in the whole of history. The trouble with debts is that they must be repaid; putting a heavy burden on every economic decision made in the country, large or small.

The 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union seemed to create what, at the time, was known as a unipolar world. Some went further still, announcing not just the end of power politics but of history itself. But the respite did not last. By 2010 Russia was beginning to come back, ready to resume the expansionist policies that, starting with Ivan IV (“the Terrible” or “the Dread,” as he was sometimes known) and ending with Stalin had been such a resounding success. By the second decade of the twenty-first century American economic supremacy, which starting in the wake of World War I had been undisputed, was also being challenged by China in a way, and on a scale, never before experienced.

Nor is the state of that other pillar of American power, its armed forces, much better. Alone of all the great empires in history, starting already in the second decade of the nineteenth century the US has been in in the enviable position of not having a peer competitor—as the current phrase goes—in its own hemisphere. This enabled it to make do with what, most of the time and sometimes for decades on end, were almost ridiculously small armed forces. Specifically land forces or, again as the current phrase goes, boots on the ground. It was only immediately before and during wartime that the situation changed and full scale mobilization was instituted. Culminating in 1941-45 when the US waged what later came to be known as 21/2 wars: meaning one in northwestern Europe, one in the far east, and one—the ½—in the Mediterranean.

Enter, once again, the Nixon administration. The “21/2” disappeared from the literature. Its place was taken by 11/2, meaning, one full scale war against the Soviet Union on “the Central Front” (Western Europe) plus a smaller half -war in some other place: either the Far East, presumably Korea, or in the Middle East on which much of the world relied for its oil. Needless to say, the figures were never accurate or even meant to be accurate. Their only use was as a very rough guide for comparison on one hand and planning on the other. Still they did provide an index concerning the direction in which things were moving.

Hand in hand with America’s declining military ambitions and expectations went very deep cuts in the size of the armed forces. The process got under way when Nixon—Nixon again—ordered an end to conscription and a switch to armed forces composed entirely of volunteers. The outcome was a 34-percent cut in the number of military personnel between 1969 and 1973. As a combination of technological progress and inflation drove costs into the stratosphere, the cuts in the number of major weapon systems—missiles, aircraft, ships, tanks, artillery barrels, briefly everything the Ukrainians are currently begging for—were, if anything, greater still. Come 1991, these forces proved adequate to fight and win a conventional war against a third-rate power, Iraq. That apart, though, almost every time they tried their hand at fighting a 1/2 war anywhere in the world they failed. So in Vietnam; so in Laos and Cambodia, so in Somalia, and so in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

Like Britain in the late 1930s, currently the US sees itself challenged on three fronts. The first is Eastern Europe where Russia’s Putin is trying to reoccupy a vital part of the former Soviet Empire and, should be succeed, get himself into a position to threaten any number of NATO countries, old or new. The second is the Middle East where Iran, using its vassals in Yemen and Syria, has been waging war by proxy on Israel while at the same time threatening Saudi Arabia, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and parts of the Indian Ocean. The third is the Far East—where America’s main allies, meaning Taiwan on one hand and South Korea on the other, may come under attack by China and North Korea respectively almost at a moment’s notice.

Even for the greatest power on earth running, or preparing to run, three ½ wars at once is an extremely expensive proposition. Especially in terms of ammunition of which, in sharp contrast to 19141-45, there simply is not enough. So far the center, though experiencing growing domestic difficulties, has not yet caved in. With the wings tottering, though, how long before it does?

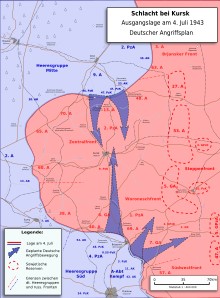

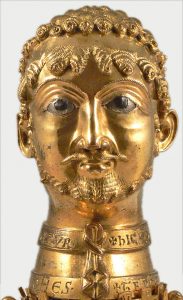

Barbarossa (Redbeard) was the nickname of the medieval German Emperor Frederick I (reigned, 1155-90) whose image graces this post. More pertinent to our business today, it was the name Hitler gave his campaign against the Soviet Union which got under way on 22 June 1941, i.e eighty years ago. Today I want to discuss a few outstanding aspects of the campaign—such as used to shape history throughout the Cold War and in some ways continue to do so right down to the present day.

Barbarossa (Redbeard) was the nickname of the medieval German Emperor Frederick I (reigned, 1155-90) whose image graces this post. More pertinent to our business today, it was the name Hitler gave his campaign against the Soviet Union which got under way on 22 June 1941, i.e eighty years ago. Today I want to discuss a few outstanding aspects of the campaign—such as used to shape history throughout the Cold War and in some ways continue to do so right down to the present day.